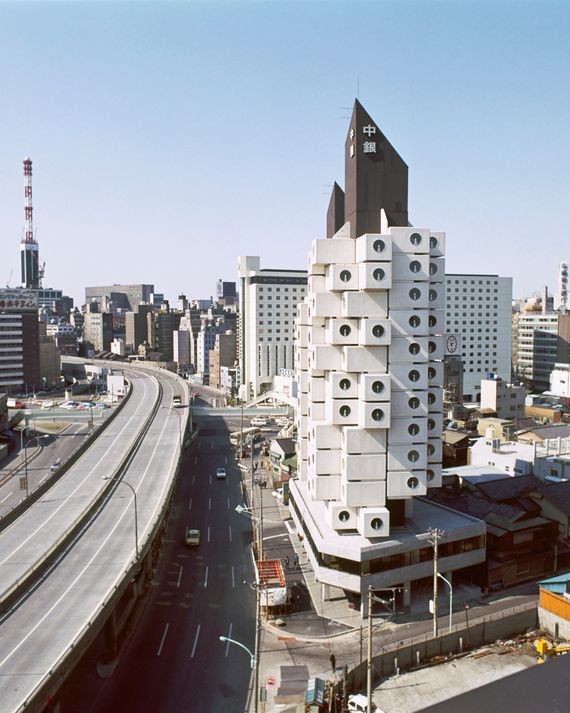

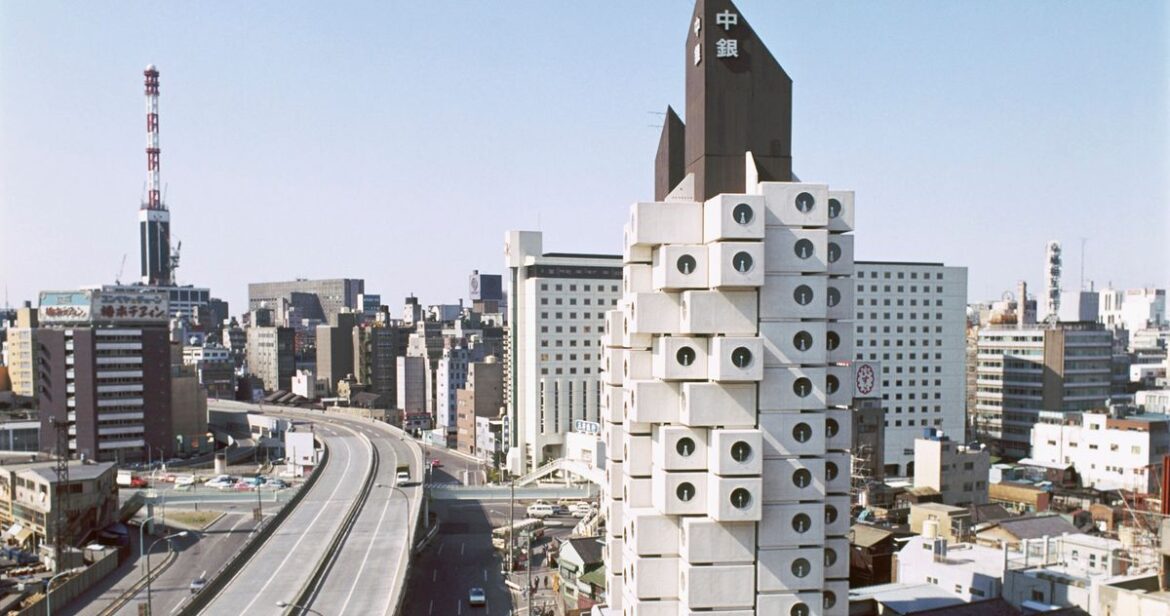

All but the most vainglorious architects imagine that their buildings will change in some small way after completion. Few declare from the outset that the majority of their structures can and should be replaced after a few decades. When Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa designed Tokyo’s Nakagin Capsule Tower in 1972, his intent was to create a building that would adapt with the future. It was, at least in appearance, truly modular with 140 steel-framed prefabricated units corbeled up and around two steel-and-concrete cores of 11 and 13 stories. Kurokawa intended that these units be removed and replaced over time, a foundational principle of Japanese Metabolism, a Japanese avant-garde architectural movement of which he was a co-founder with Kiyonori Kikutake and Fumihiko Maki. They held that buildings should evolve like organic material, and the Nakagin tower became one of the most recognizable icons of the style.

Subsequent decades didn’t result in healthy metabolic processes; there was decay but no regeneration. The tower in Ginza was eventually deemed too expensive to repair. It was torn down in 2022 and will be replaced by a luxury hotel. Demolition, in this case, involved not a single implosion but the more incremental removal by crane of each of the original capsules, which at least made retaining a few of them easier. The Nakagin Tower Preservation and Restoration Project, led by former resident Tatsuyuki Maeda, actually chipped in to cover the demolition costs in return for 23 of the units — a little like tipping the firing squad not to aim at your face — but nevertheless, a tradeoff we were lucky to have.

The surviving capsules were dispersed around the world. SFMoMA acquired Kurokawa’s own capsule (bastards), there are a few in museums and galleries in Asia, two in a Japanese seaside hotel, and one was used as a DJ booth at a mall in Ginza. The one acquired by the Museum of Modern Art now serves as the centerpiece of its exhibit on the tower and its architect, “The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower,” curated by Evangelos Kotsioris and Paula Vilaplana de Miguel. New York museums feature all sorts of fragments of vanished structures by architects from Louis Comfort Tiffany to Louis Sullivan, but most — even the period “rooms” — fall short of being properly that and usually consist only of surface décor and not structure. Thankfully, here we can encounter the complete capsule in all its glory.

Installation view of The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower, on view at MoMA.

Photo: Jonathan Dorado

Capsule A1305 from the Nakagin Capsule Tower. 1970–72, restored 2022–2023. Steel, wood, paint, plastics, cloth, polyurethane, glass, ceramic, and electronics.

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

It is indeed enthralling to see A3105, the unit from the tower’s pinnacle, up close. Even non-museumgoers can catch a glimpse of it from MoMA’s ground-floor windows, which are open to the street, like a sales gallery for a building that will never rise again. The interior, which you can’t enter but can peer into from both its rounded window and doorway, is terrifically sleek and mod, a futuristic look not at all belied by its built-in rotary phone, flip clock, 13-inch television, and reel-to-reel tape recorder (which cost extra for hours of fun). It’s all packed into a space that’s a bit over 8 by 13 feet, where nearly everything is built in, from angled cabinets to a fold-down desk. The bathroom looks like one you would see on a spaceship, lined with cast plastic in one nearly continuous surface and accessed by a very cool pill-shaped door. And the single rounded window in the unit, which calls to mind a porthole, seems very generous in person with a diameter of more than four feet. There’s a clear link to the industries that Kurokawa admired, from Mercury spacecraft to shipbuilding, planes, Airstream, and cars, all of which were rapidly modernizing at the time, as was the design of their interiors. The capsules themselves were produced by a company that makes shipping containers, while Noburu Abe, who worked on the interior, modeled it on a sailing cabin. There’s an air of 2001 and Solaris; Black Widow more recently seems to have ripped off the design.

Besides the capsule itself, the exhibit has an interactive 3-D interface that permits you to wander the halls of the buildings virtually via a video-game console, and the experience is illuminating; there are very few right angles, no long deadening hallways, and the capsules seem to be staggered a few steps up from the one before, like cells attached to a central stem. There are also plenty of promotional materials dating from the building’s launch, and in one video clip, Kurokawa sells the merits of the building to an impassive audience of smoking businessmen. The units sold out rapidly, so someone was impressed.

Night time at the Nakagin Capsule Tower with Takayuki Sekine seen through the window of capsule B1004 in 2016

Photo: Jeremie Souteyrat

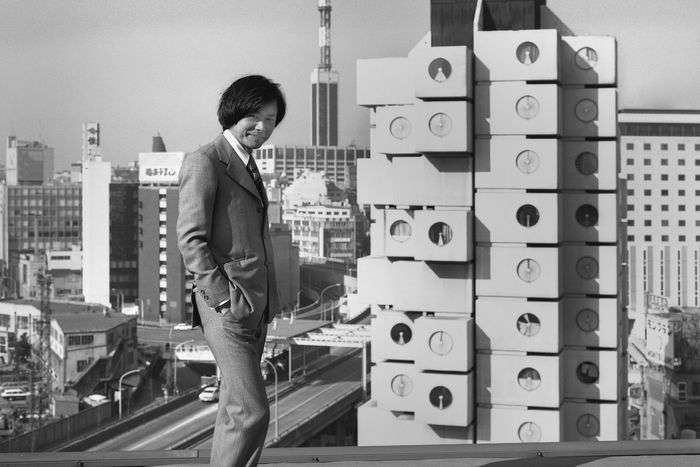

Kisho Kurokawa was a figure for whom there’s really no American analogue. Sure, his interest in Metabolism placed him squarely in the ranks of 1960s architectural fantasists; he imagined Helix Cities, a Linear City, floating factories, and much else that was dubiously buildable. But unlike, say, the Archigram coterie in the U.K. or Lebbeus Woods from our own shores, he was a very prolific architect of real-world structures, designing museums, airports, stadiums, and even a space-capsule disco. As Charles Jencks commented in his introduction to Kurokawa’s Metabolism in Architecture, “Here were the Metabolists, who had actually built buildings, while European groups like Archigram hadn’t.” He was also unquestionably hip, both sartorially and in his works (the very groovy cover of one of his books is blown up on a gallery wall), made very frequent television appearances, and was later even a founder of the Japanese Green Party. As a prolific author and theorist, his techno-futurist pronouncements (declaring that “the capsule is cyborg architecture”) were also leavened with allusions to Buddhist concepts like samsara.

Nakagin’s architect, Kishō Kurokawa, in front of the completed Nakagin Capsule Tower in 1974.

Photo: Tomio Ohashi

Then there’s the context of postwar Japan. In a 2005 interview with Rem Koolhaas in the Dutch architect’s Project Japan: Metabolism Talks, Kurokawa explained that the bombardment and near leveling of his hometown of Nagoya in World War II, and the general postwar landscape of bombed-out cities across Japan heavily influenced Metabolist thinking. Kurokawa also pointed Koolhaas to the Ise Shrine south of Nagoya, one of the principal Shinto sacred sites. “The shrine is 1,200 years old, it’s true, but it’s reconstructed every 20 years. Do you understand? Everything we see is impermanent,” he said. Kurokawa was decidedly not an advocate for disposability, however. As he wrote in his Metabolism treatise, “If spaces were composed on the basis of the theory of the metabolic cycle, it would be possible to replace only those parts that had lost their usefulness and in this way to contribute to the conservation of resources by using buildings longer.”

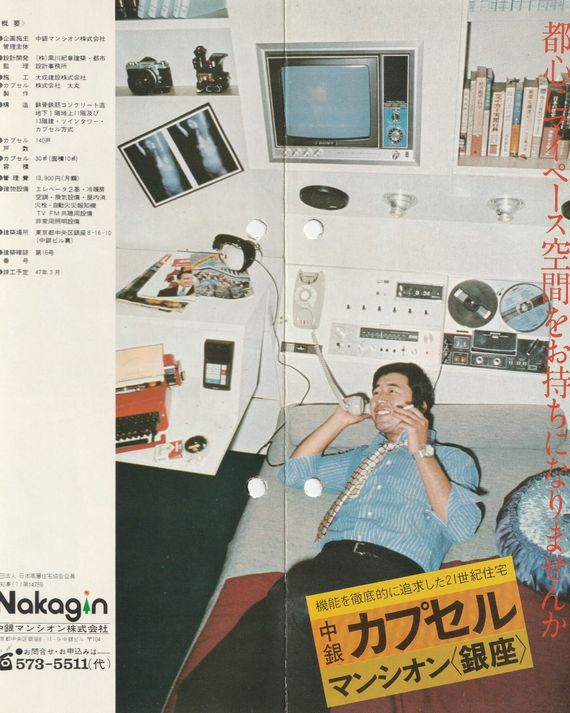

The Nakagin tower came from, of all things, a radical convention. Art Nouveau had the 1900 Paris Exposition; the Metabolists had the 1970 Expo in Osaka. Kurokawa built his Takara pavilion, a stainless-steel frame containing stainless-steel boxes (a photo is featured at the exhibit), and a capsule house he designed was suspended from a Kenzo Tange frame. The chairman of Nakagin, a real-estate company, was won over. He wanted a building, and the concept was simple; pieds-à-terre for salarymen. The promotional brochure in the exhibit presents that ideal resident lounging on the bed, smoking a Marlboro while talking on the phone.

On the 1971 cover of a promotional brochure for the Nakagin company, it says, “A twenty-first century home that thoroughly pursues functionality: Nakagin Capsule Manshon (Ginza).”

Photo: Courtesy Tatsuyuki Maeda / The Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project, Tokyo, Japan

The tower was a commercial and critical success, even if the dream of a capsule life was rather short. In this, it followed the dim fate of many prefabricated housing schemes. These efforts achieved scale in planned economies such as the Soviet Union, East Germany, and Poland. Elsewhere most would sputter out quickly; Moshe Safide tried at Habitat in Montreal and then again in Baltimore before giving up, as most did. More recently, the B2 Modular tower next to Barclays produced lawsuits, not progeny. Kurokawa used capsules subsequently only in a handful of projects; his former house is available to rent, and his Capsule Inn in Osaka remains operational. There are clear economies to be had from these methods, but only if enough builders take them up, which they haven’t.

Nakagin itself fared well into the ’80s, but material degradation began to take its toll. A fundamental problem for any repair proposition was that it wasn’t possible to remove single units without taking out the full stack above them; this Jenga tower was already at its structural limit. All of the pods incorporated that sinister silicate asbestos. Corrosion and water damage increased; the hot-water system eventually failed entirely. Kurokawa (who died in 2008) was ready with plans for renovation — in fact, for somewhat larger capsules to plug in — but these never quite came about. The surroundings had become a good deal more glam over time, including a 48-story Jean Nouvel building across the street. The residents voted on their future and, despite a real movement for preservation, most voted for demolition and a check.

Wakana Nitta (a.k.a. Cosplay Koe-chan) in her capsule, which she uses as a DJ booth.

Photo: Courtesy Tatsuyuki Maeda / The Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project, Tokyo, Japan

Noritaka Minami, A503 I, from the series 1972 (2010–22), 2017.

Photo: Noritaka Minami

A welcome aspect of the exhibit is that the building’s twilight years are not an afterthought; photos by Noritaki Minami from between 2010 and 2022 detail the last decade or so of the Nakagin Tower and the residents who still very much valued these units. The tower had become quite a different place; no longer a cluster of bachelor or worker pods, it hosted residents who were drawn to Nakagin for its premise and its architecture; architectural historians, DJs, and writers, about half of them women. The experience was all rather the reverse of J.G. Ballard’s High Rise — as the building began to decay, it drew residents together. The monograph about the exhibit stresses that in its twilight years, it “paradoxically acted as a social condenser,” with residents visiting a nearby bathhouse together (for hot water they didn’t have at home), gathering in lobbies during earthquakes, and grilling fish on the bridges connecting the two towers. Photos of the units when actually occupied certainly don’t look like the pristine capsule on display but surely appeal.

The capsule also calls to mind an experiment closer to home. New York faces more intensive pressures on housing costs than Tokyo, and microunits à la Nakagin are often mentioned as a possible solution. This hasn’t happened for a variety of reasons. All other aspects of the debate aside, the iterations we have, such as Alta+ in Queens, often look dismal. And yet Nakagin, dated as it might look now, manages to make tiny-apartment living still look attractive. It’s difficult not to wonder if actually appealing and functional design might sweeten the proposition.

There’s also, of course, the critique that microunits, at Nakagin or not, are simply too small for comfort. Nakagin is a museum exhibit and not a showroom; it’s easy to overlook the fact that the windows aren’t operable and that there’s no kitchen (a salaryman special). And yet there’s an unquestionable high-tech Zen verve to the space.

The exhibit raises questions too about the basic premise of Metabolism: that buildings should adapt and change over the years. We don’t doubt that, when the building needed it, Kurokawa would have updated his capsules, perhaps radically. But it’s difficult to be confident that subsequent architects would have, and what the quality of those changes would have been. Much of the immense aesthetic appeal of Metabolism was its unfinished look — the future that hasn’t arrived is almost always more appealing than the one that does. This might simply be a reflection of the fact that not that many Metabolist structures were ever built, and they became objects to be prized instead of scaffolds for creative evolution. That is the fate that seems to have befallen the capsules scattered around the world and at the MoMA. That destiny was, as curators note in the exhibition catalogue, something that Kurokawa himself envisioned, if not quite in this form. As he wrote: “The capsule means emancipation of a building from land and signals the advent of an age of moving architecture.” In a curious way, Nakagin is finally free to roam.

The fold-out desk in the capsule and a view of the street through the round window of the capsule, which looks out through the ground-floor window of the MoMA.

Photo: Jonathan Dorado

“The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower” is on view at the MoMA through July 12, 2026.

Related

AloJapan.com