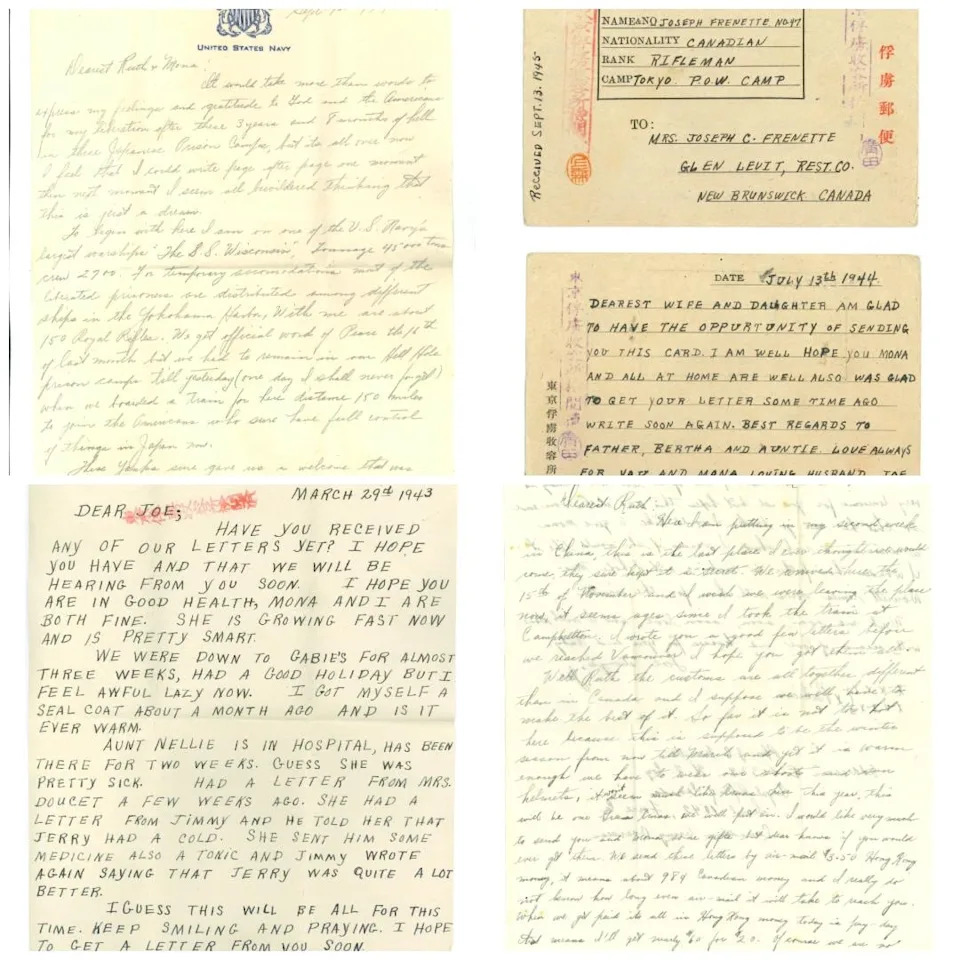

The first letters that Joseph Frenette sent his wife Ruth from Hong Kong in 1941 are filled with detail.

“Dearest Ruth, here I am putting in my second week in China,” Frenette wrote in one letter. “It seems ages since I took the train at Campbellton. The customs are altogether different from Canada so I suppose we will have to make the best of it.”

As a new soldier with the Royal Riffles of Canada and drafted in the Second World War, he wrote about the food, and what soldiers wore in mild November weather.

He even lamented about missing the snow that his wife and their daughter Mona were likely to get back home in Glen Levit, near Campbellton.

Soon, though, the tone of Frenette’s writing abruptly changed and the intimate details he used to fill pages of thin writing paper with disappeared.

“I am glad to have the opportunity of sending you this card. I am well. I hope you, Mona, and all at home are well also,” Frenette wrote on July 13, 1944.

His loved ones would not have known from his letters that for more than three years, Frenette had been a prisoner in a Japanese war camp, enduring unlivable conditions.

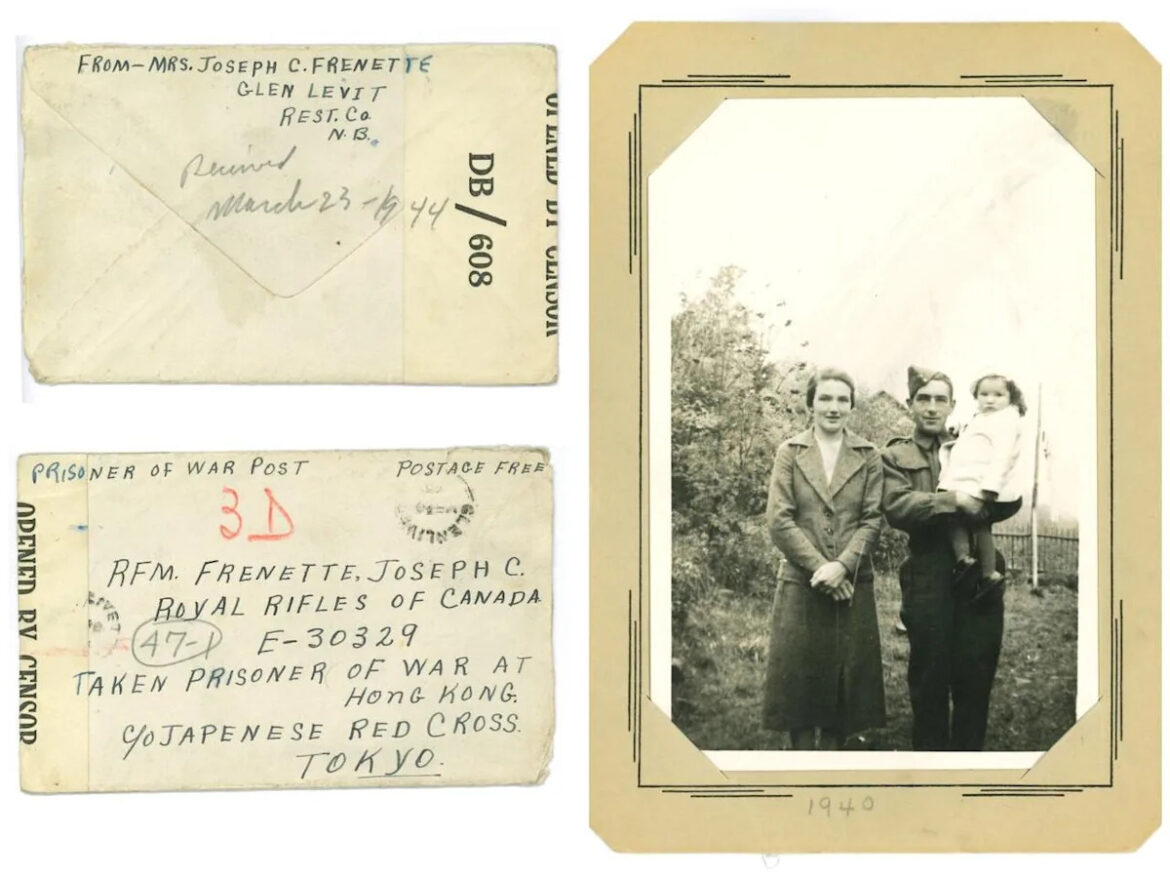

Joseph Frenette’s family donated to the New Brunswick Military History Museum about 100 letters from his time in a Japanese war camp in the 1940s. (Submitted by the New Brunswick Military History Museum)

“He’s kind of putting on a brave face … because he wasn’t able to say too much — or anything really — about the horrible conditions in which the Japanese were keeping them,” said David Hughes, a retired captain and manager of the New Brunswick Military History Museum.

More than 2,000 Canadians soldiers were captured and imprisoned by the Japanese Imperial Army during the battle of Hong Kong in the early 1940s. Many were brutally murdered, or mercilessly shot as they surrendered on the battlefield.

Frenette is one of the few New Brunswickers who survived.

Now, his family has donated a collection of his letters, diaries, medals and other belongings for a special display at the New Brunswick Military History Museum in honour of the 80th anniversary of Victory over Japan Day.

More than 200 New Brunswickers sent with Allied forces

There were no New Brunswick units in Hong Kong, which was a British colony that was taken over by Japan from 1941 to 1945, during the Second World War but many ended up there anyway.

“The Royal Riffles of Canada, a Montreal-based unit, before they deployed to Hong Kong, they took on a big draft of soldiers — over 200 of them from New Brunswick,” Hughes said.

Frenette and his fellow soldiers had no idea where they were headed, but they were destined to help other Allied forces defend Hong Kong and keep Japanese forces out.

Joseph Frenette, pictured here, served with the Royal Rifles of Canada during the Second World War and was captured by Japanese forces during the Battle of Hong Kong. (Vanessa Vander Valk/CBC)

More than 500 members of the unit were killed in the initial attack or shortly after in captivity, Hughes said.

“More New Brunswickers were killed, wounded or captured at the battle for Hong Kong than any other battle of the Second World War.”

Frenette spent over three-and-a-half years inside a Japanese prisoner of war camp. It’s likely he was doing slave labour in an industrial factory during his time there, Hughes said.

The Japanese army followed a set of rules at the time known as the code of Bushido, which was a medieval warriors code.

“Basically, it was a cover for them to allow themselves to commit atrocities against their enemies,” Hughes said.

Prisoners endured starvation, brutal beatings, forced labour and faced disease with no proper medical support.

Through it all, Frenette wrote letters home. Those letters are a testament to his will to get home, despite an army trying to control what little contact he did have with his loved ones.

Correspondence was limited, controlled and even faked

Prisoners were not allowed to share what happened inside the camps, which kept Frenette’s reality hidden from his family.

The small postcards that soldiers used only had eight lines on one side. Family members who sent replies were just as limited in their communication.

“They were only allowed to write less than 30 words, these were short,” Melinda Jarrettt, who also works at the New Brunswick Military History Museum, said. “There was no room for I love yous [or] long conversations.”

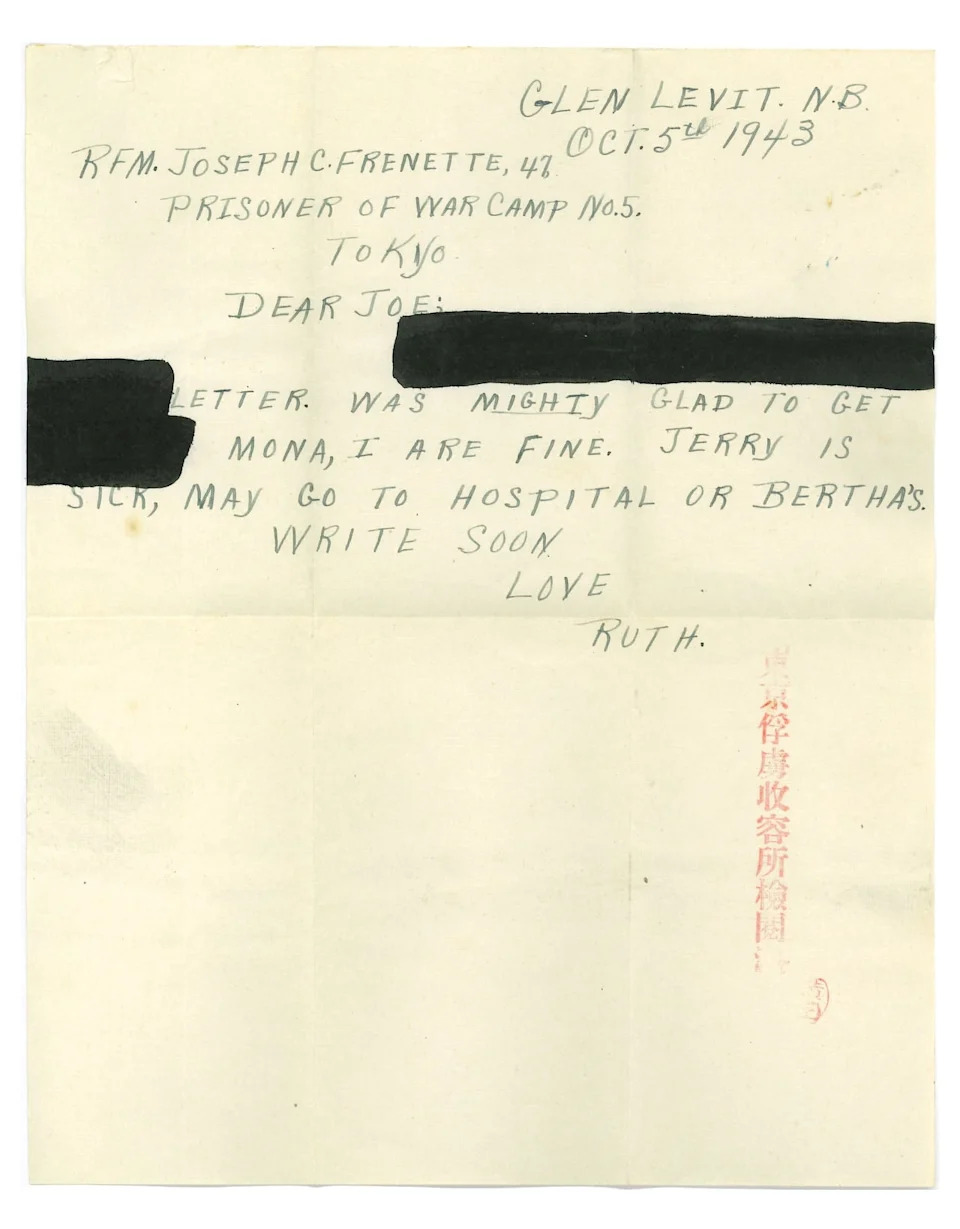

Japanese soldiers went through loved ones’ letters and redacted entire lines from them if they contained information that they didn’t want soldiers to know. They weren’t allowed to write in cursive — only big block letters.

Part of a letter from Frenette’s wife Ruth dated Oct. 5, 1943, pictured here, was redacted in big black marker. (Submitted by the New Brunswick Military History Museum)

“The fact that he was able to maintain these letters and his diaries, and them not be destroyed in the horrible conditions of the Japanese prisoner of war camps is something of a mystery,” Hughes said about Frenette’s collection.

Japanese officers also crafted false messages, written as if they came from soldiers, to be sent to their families.

“They wanted the world to think that they were treating PoWs well,” Hughes said. “That was obviously not the case.”

In some cases, they made prisoners record the messages themselves to be transmitted across radio frequencies overseas.

In Frenette’s case, an officer read a message signed by him, in hopes that his family would hear it.

“Dearest wife and baby, I hope these few words will reach you by the radio,” the voice of an officer read in Frenette’s name.

“I am in good health and I’m in a new prison camp in Japan not far from Yokohama. We are well treated by the Japanese. We are so glad to take this opportunity to let you know I have received your letter last week and [it was] the happiest day of my life since I was taken prisoner. I hope that when this message is broadcast, that Jacquet River and Glen Levit will be listening in. … Keep smiling now. With all my dear love … hope to hear from you soon again. Your loving husband, Joseph Frenette.”

On Sept. 10, 1945, Frenette wrote a special letter himself, sharing the news that he and other soldiers had finally been liberated from the camps.

“It would take more than words to express my feelings of gratitude to God and the Americans for my liberation after these three years and eight months of hell in these Japanese prison camps,” he wrote. “But it is all over now. I feel that I could write page after page one moment, then the next moment, I seem all bewildered, thinking that this is just a dream.”

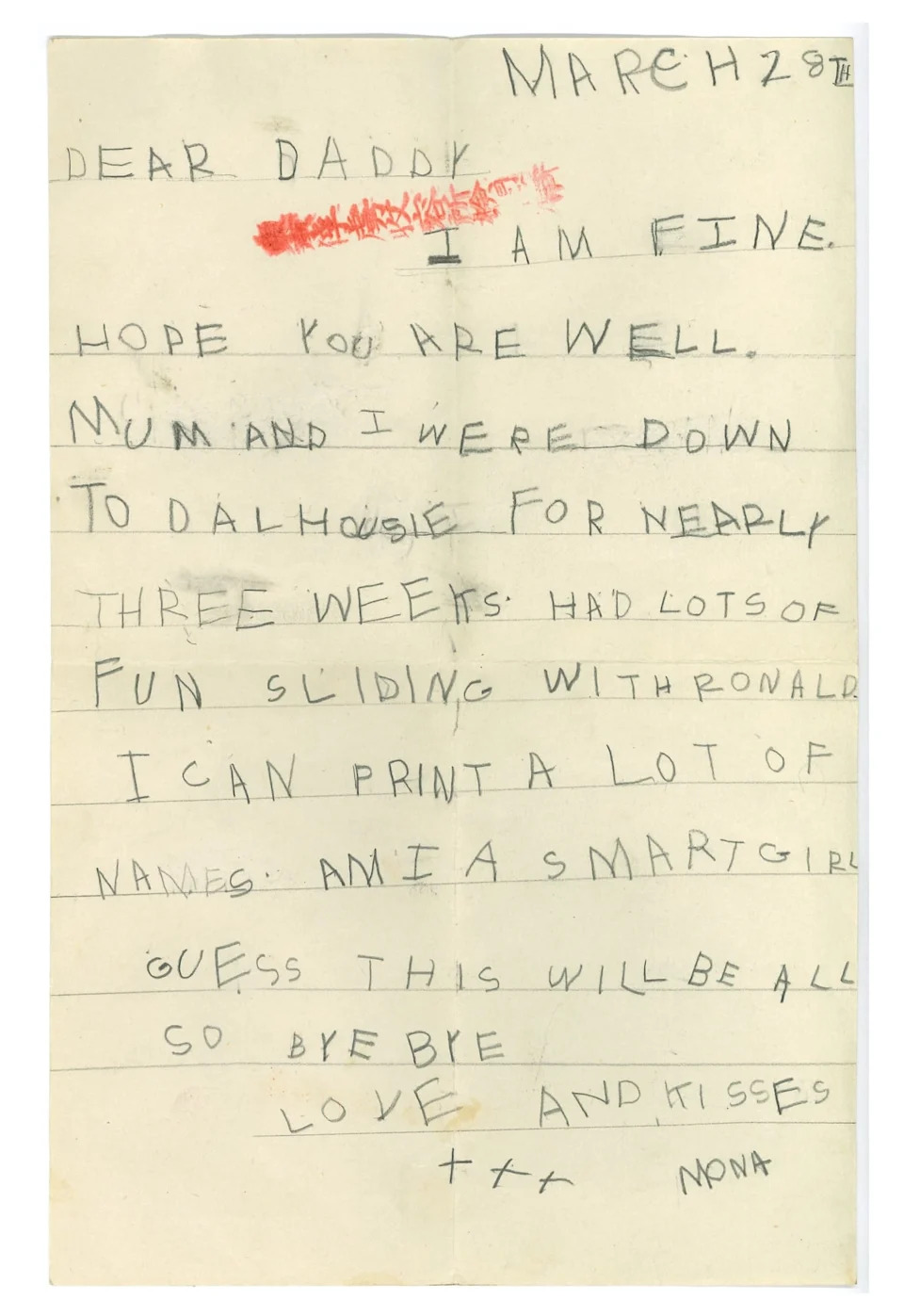

Frenette’s daughter Mona also sent her father her own letters during the war. She is 84 years old today. (Submitted by the New Brunswick Military History Museum)

Frenette eventually made it home to his wife and daughter, and the couple later had a son.

Frenette suffered from post-traumatic stress and had to leave his teaching job as a result. He and his family moved to Moncton, where he eventually retired from a job at Canada Post.

He died in 1979.

Jarrett said members of the public or family members of people who have served can view the letters and artifacts if they get in touch with the New Brunswick Military History Museum.

In the meantime, she said staff are preparing a new, permanent exhibit dedicated to Japanese prisoners of war thanks to the families who have recently made donations.

“This is a story that they grew up with,” Jarrett said. “They’re very honoured to see that this is going to be recognized in New Brunswick because it’s been a long time coming.”

AloJapan.com