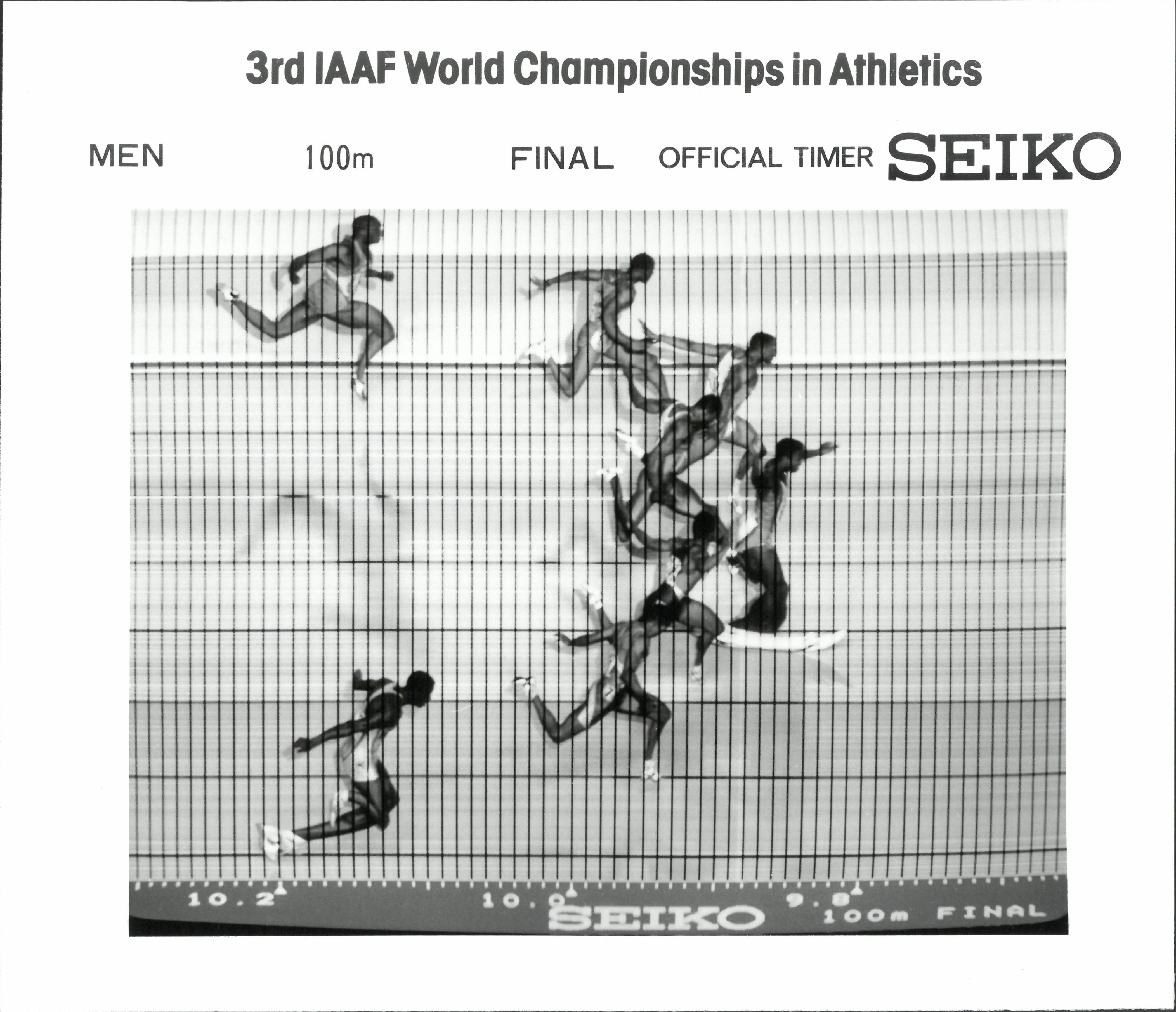

Among the 200 artefacts on display in the MOWA Heritage Athletics Exhibition Tokyo 25, open since 6 July at the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) building, visitors can see for the first time the original photo finish of Carl Lewis’s 100m world record set during the World Athletics Championships in Tokyo on 25 August 1991.

The print on display shows 9.86 seconds and is accompanied by the official ratification form signed by starter Hideo Iijima, a former Japanese sprinter who competed at the Tokyo 1964 Olympics and once came within a tenth of a second of the world record with 10.1.

Innovating timing by video

The print comes from the Seiko Slit-Video 1000 HD, a line-scanning video device that made its debut at the World Championships in Tokyo in 1991. The Seiko system arrived after the IAAF (now World Athletics) Congress in Barcelona in 1989 authorised the use of video devices to determine times and placings.

This innovative method brought a clear advantage: results could be produced and published far more quickly. Previously, photo finish systems relied on film negatives that had to be chemically developed into a visible photograph, or on instant Polaroid prints that still required time to reveal – processes that delayed final decisions.

There was no need to recheck the photo: Lewis won by a very clear, albeit tiny, margin over his US teammates Leroy Burrell, who ran 9.88 – also under his own world record of 9.90 set just two months earlier – and Dennis Mitchell, who ran 9.91.

WCH Tokyo 1991 100m world record photo finish (© MOWA)

For the first time in history, six men ran under 10 seconds in this final, which was presented as the fastest race ever.

A visually striking and officially decisive picture

Automatic timing goes back farther than most people realise. A demonstration device was used at the Oxford vs Cambridge Varsity match at Lillie Bridge in West Brompton, London, in 1874: a large clock was triggered by the starter’s pistol and stopped when the winner broke a finishing-line thread. In the 1930s, cinematographic systems that recorded runners and a stopwatch on the same film were used at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles in 1932 and Berlin in 1936.

Photo finish cameras began to be used regularly starting with the London 1948 Olympics. In its own way, the photo finish is a fusion of space and time: it produces an image of infinitesimal thickness that unfolds backward, which is why the athletes’ bodies appear stretched and ghostlike. The result is both visually striking and officially decisive.

The MOWA Heritage exhibition in Tokyo

The visual of Lewis’s photo finish is central to the exhibition’s identity, which pays tribute to the major championships hosted by Tokyo.

The red rising sun on a black background references the opening of the official film of the 1964 Games by Kon Ichikawa, a visual also seen on the film’s poster, overlaid with the photo finish of Bob Hayes, the fastest man of 1964.

One can already recognise the highly graphic appearance of Seiko’s photos, with vertical lines marking every hundredth of a second, making it easy to “read” the image.

To make a historical connection with the 1991 World Championships, Lewis replaces Hayes in the image, and the brush-style calligraphy is part of the visual identity of both Tokyo 1991 and 2025.

In the pursuit of saving time

Seiko’s 1991 original documentation explains the leap this machine represented: the Slit-Video 1000 HD replaced film-based cameras by storing images electronically on MOS memory devices, making them “available instantaneously without the need to develop film.”

The system used HDTV line scanning to generate high-definition images, and an automatic time reader that could display times to the hundredth or even thousandth of a second once the cursor was placed on the winner. By removing the need for film development, decisions on close finishes could be made much faster than before.

The same principle will be used in Tokyo in 2025, except now in colour, and the current camera can extract times to 1/10,000 of a second, equivalent to about one millimetre for a sprinter, roughly the thickness of a jersey and bib combined.

To close the exhibition story, Seiko has generously lent two important pieces to MOWA Heritage Tokyo 2025: the countdown clock that marks the time until the opening of the World Athletics Championships, and the last lap bell used for middle-distance races. These objects continue the link between timing technology and the drama of competition, a fitting tribute to moments like Lewis’s 9.86, when precision and poetry meet at the finish line.

You can find the 1991 printout in the virtual 3D museum among other iconic photo finishes and pictures in the gallery of the 1984-1999 era of the Timeline Tunnel.

Pierre-Jean Vazel for World Athletics Heritage

AloJapan.com