In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an artistic revolution swept the world, fundamentally challenging established cultural frameworks. This new energy found fertile ground in Japan, where a postwar momentum for breaking societal norms amplified avant-garde activity. This wave was termed “underground,” adopted into Japanese as angura, a shortened form of the loanword andaguroundo. Though short-lived, spanning roughly from 1966 to the mid-1970s, the underground scene profoundly influenced Japanese cultural expression.

The exhibition Tokyo Underground 1960–1970s: A Turning Point in Postwar Japanese Culture, recently staged at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, explored this movement through its ephemera: movie posters, flyers, magazines, books, festival programs, admission tickets, brochures, handwritten correspondence, vinyl records, and archival photographs. Cocurator Kei Osawa, a research fellow at the University Museum, University of Tokyo, drew the materials from his personal collection, amassed over some twenty years. “When I started, postwar ephemera went unnoticed and I became interested in printed materials that weren’t collected by libraries or art museums,” he said.

Installation view of Tokyo Underground 1960–1970s, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2025. Photograph by Furukawa Yuya

Installation view of Tokyo Underground 1960–1970s, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2025. Photograph by Furukawa Yuya

Courtesy Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

The printed matter, organized in glass displays and wall-mounts snaking around a gallery with black walls and high ceilings, was augmented with detailed chronologies covering momentous years of social turmoil: the start of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution; the Beatles’ Japan tour; the arrival of a US nuclear-powered aircraft carrier at Sasebo port amid fierce opposition; protests at the University of Tokyo; the Apollo 11 moon landing; the first women’s liberation demonstration; the restoration of diplomatic relations between Japan and China.

Films catalyzed the Tokyo scene at this time. On June 29, 1966, filmmaker Kenji Kanesaka organized “Underground Cinema,” a screening of experimental work from the United States. The venue was the Sogetsu Art Center, the epicenter of experimental art in Tokyo, where Yoko Ono had first performed her legendary “Cut Piece,” in 1964. From there, countercultural ideas rapidly spread across music, art, manga, theater, butoh dance, and film.

The Mori exhibition revealed Tokyo’s underground to be both interdisciplinary and international. “We don’t feature photography as a discrete field,” Osawa noted. “Photography, like graphic design, was a medium that permeated every area.” At a time when avant-garde art was increasingly non-object based, performative, and politically charged, printed matter served as a tool of transmission.

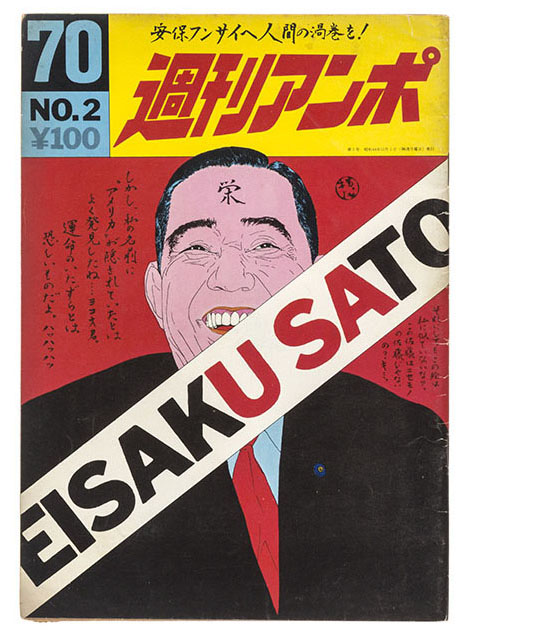

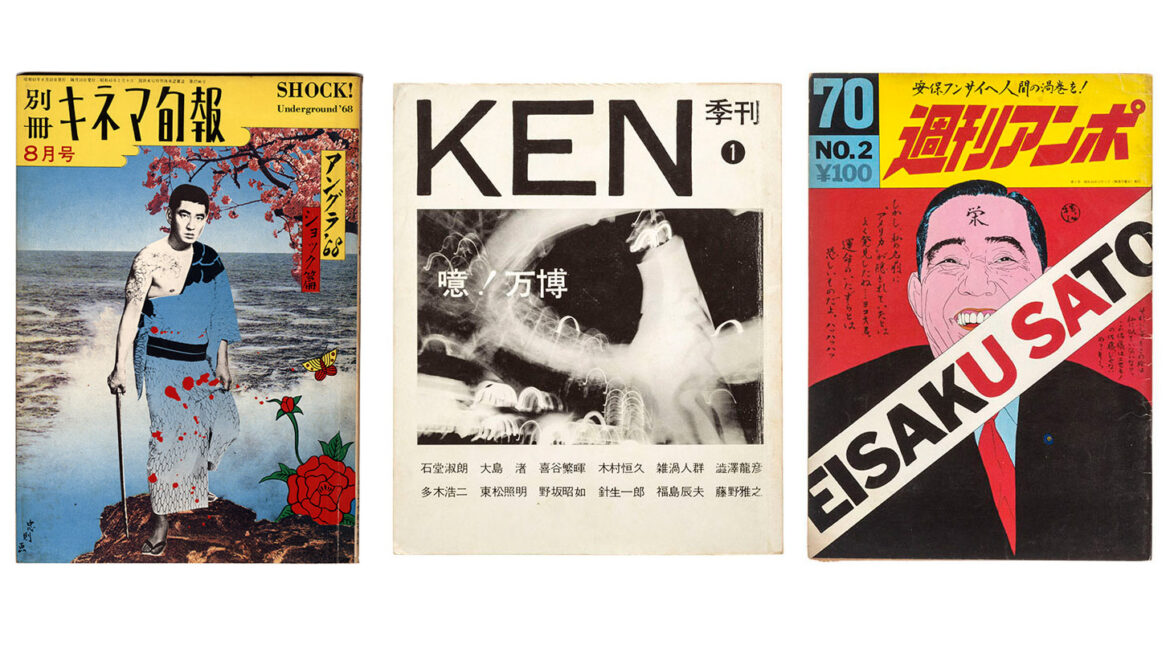

Shūkan Anpo, vol. 2, December 1, 1969. Published by Shūkan Anpo-sha, Tokyo

Courtesy Goliga Books

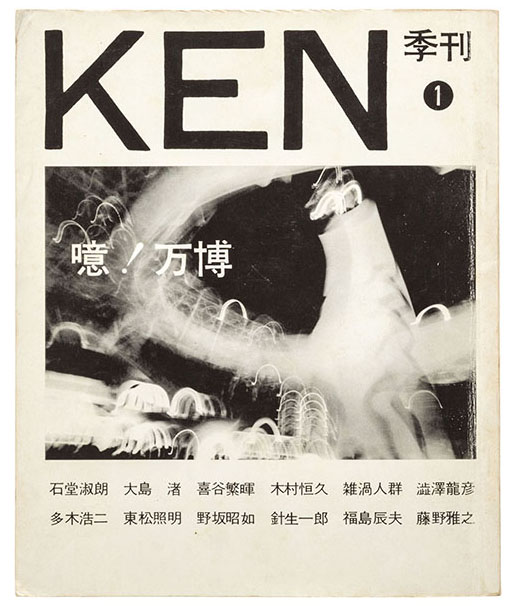

Ken, vol. 1, July 1, 1970. Published by Shaken, Tokyo

Courtesy Goliga Books

The bustling nightlife district of Shinjuku was the primary stage for this cultural ferment. As a major city center within the megapolis—a place where many train lines converge—Shinjuku is a diverse, transitory space. During this period, its plazas, cafes, stores, and event venues held impromptu gatherings and theatrical performances. The independent production company Art Theater Guild, for example, converted the basement of their cinema in Shinjuku into the Scorpio Theatre, and the underground movement coalesced around this screening venue and gathering spot. Its importance was evident in Tokyo Underground, where two dozen framed posters of films and theater plays covered a far wall, floor to ceiling. The posters’ screen-printed designs, several on metallic paper, presented a range of eerily fresh typography and graphic styles.

The exhibition also documented the era’s anti-establishment protests, including opposition to the Vietnam War and the Osaka World Exposition, in 1970. A long, horizontal poster commemorated the “Anti-Expo Black Festival,” in 1969, organized by the performance troupe Zero Dimension. The image shows a tangle of naked bodies evocative of Dante’s Inferno. Activists viewed the Expo as an attempt to smooth over the imminent renewal of ANPO, a controversial security agreement with the United States that allowed for an indefinite American military presence on Japanese soil.

Poster for Sogetsu Cinematheque: Underground Cinema, Japan and USA, 1966. Design by Hosoya Gan

Poster for Sogetsu Cinematheque: Underground Cinema, Japan and USA, 1966. Design by Hosoya Gan

Courtesy Keio University Art Center

The West Exit Plaza of Shinjuku Station was a key gathering spot for young people, artists, entertainers, and activists. In an attempt to reclaim public space and quell spontaneous gatherings (often protests), the government officially rezoned the area to prevent people from assembling. In 1968–69, protests in the city, as well as in other parts of the country, were relatively common. Japan’s largest university, Tokyo University, was often a veritable battlefield with students pitted against riot police. By the mid-1970s, however, the protest movement waned and the country entered a new phase of economic development. The underground effectively disappeared. Former participants dispersed—some pursuing spiritual paths, others adapting to new cultural currents or entering the mainstream arts.

The exhibition effectively preserved and revived this history through its material record. “What digital images lack, beyond texture, is a sense of scale,” Osawa said. Indeed, the physicality of the objects in Tokyo Underground reflected the politically charged atmosphere of these years and how those ideas were communicated. Considering the ephemera today, one becomes aware of a shift in how cultural movements form and spread, prompting questions of where—in our current era of surveillance capitalism and platform-modulated expression—are today’s spaces that resist regulation and homogenization?

Tokyo Underground 1960–1970s: A Turning Point in Postwar Japanese Culture was on view at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, from February 13 to June 8, 2025.

AloJapan.com