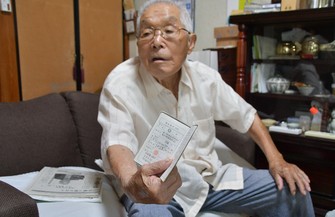

Kazuaki Yamashita, who was sent to fight in the Battle of Okinawa during World War II and lost many friends, is pictured in Kunisaki, Oita Prefecture, on Aug. 5, 2025. A scar from a gunshot wound inflicted by U.S. forces remains on his left arm. (Mainichi/Takayasu Endo)

KUNISAKI, Oita — During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War, some 2.3 million Japanese soldiers and military personnel lost their lives, along with around 800,000 civilians. One former soldier from southwest Japan’s Oita Prefecture was placed on the front lines in Okinawa during World War II amid flying bullets when he was still a teenager. There he witnessed the brutal deaths of his comrades, who fell one after another. Still aching from the fragments of a U.S. hand grenade lodged in his body, the former soldier has shared his story with the Mainichi Shimbun.

Friend with fatal wound hands over part of own finger

“Only four out of 54 survived,” recalls 97-year-old Kazuaki Yamashita, as he spreads out a handwritten list of names at his home in the Oita Prefecture city of Kunisaki in early August.

During the final stages of World War II, 54 members of the Sasebo Naval Corps were sent to Okinawa, where fierce ground battles raged between Japan and the U.S. Of the 54, only four including Yamashita returned alive, and he is now the sole survivor.

It was in December 1944, at the age of 17, that Yamashita was sent on a ship from Sasebo in Nagasaki Prefecture to Okinawa Prefecture’s main island via Kagoshima. He was assigned to the Oroku Detachment of the Navy Air Service, which had only a few operational fighter planes.

Kazuaki Yamashita is pictured in 1943, before being sent to the battlefields of Okinawa, at his family home in Kunisaki, Oita Prefecture. This photograph of the picture was captured on Aug. 5, 2025. (Mainichi/Masanori Hirakawa)

In April 1945, U.S. forces landed on Okinawa’s main island. Around that time, Yamashita was ordered to go to army territory near Shuri (present-day Naha). Lacking firearms, he took a machine gun meant for fighter planes from a warehouse, but when fired, it quickly overheated, rendering it unusable.

Before long, U.S. forces closed in and were only about 200 meters away. Yamashita heard bullets whizzing by. Intense bombardment from the sea and air followed, and his comrades were killed one after another, their bodies left unrecognizable.

A friend from Yamashita’s hometown was hit by a shell in the back and died before his eyes. Just before passing away, the friend bit off the tip of his pinky finger and handed it to Yamashita. Yamashita took this as a request to take it back to their hometown and placed it in his uniform pocket.

Defeat an ‘inevitable outcome’

Yamashita, too, was shot in the ankle, and gave up fighting. He also suffered hearing loss, possibly due to his eardrums rupturing from the sound of explosions. Using his military sword as a cane, he crawled south with a comrade, climbing over countless corpses.

Kazuaki Yamashita is pictured in Kunisaki, Oita Prefecture, on Aug. 5, 2025. He lived his life after the war with the feeling of “being sorry for surviving and coming back.” (Mainichi/Takayasu Endo)

When he reached the southern coast of Okinawa’s main island, he saw hard-pressed people throwing themselves off a cliff. In a natural cave where Yamashita hid himself, a hand grenade thrown in by U.S. forces exploded, embedding fragments in his behind and his elbow.

On Aug. 15, 1945, Yamashita was in a U.S. internment camp. The letters “PW” for “prisoner of war” were written in large letters on his jacket. “Japan has lost,” he was told, but he felt nothing. It seemed an inevitable outcome.

Before being dispatched to Okinawa, Yamashita had worked at the Sasebo Naval Arsenal, where he was involved in the production of suicide motorboats like the “Shinyo.” Seeing how the Japanese army was having to carry out attacks predicated on its own soldiers’ deaths, he felt “We’ve come to a bad place.” In actual fact there was an overwhelming disparity in troop strength and the quality and quantity of weaponry compared to the U.S. military.

Grenade fragments still cause pain

It was about a year and two months after the war ended that Yamashita returned to his hometown in Oita Prefecture. The first place he visited was the home of the friend who had entrusted him with the part of his pinky finger. The friend’s father already knew of his son’s death and was grateful for the return of the “memento.”

Kazuaki Yamashita is pictured in Kunisaki, Oita Prefecture, on Aug. 5, 2025. Shrapnel from a U.S. hand grenade remains in his left elbow. (Mainichi/Takayasu Endo)

Yamashita took over a farm after the war, but due to the aftereffects of his injuries, he found physical labor difficult, and so he gave up on it and became a truck driver. The grenade fragments in his rear still cause pain, and he can only sit in soft chairs. A fragment left in his left foot caused internal bleeding when he was in his 80s, so he had it surgically removed.

After the war, local elementary schools asked Yamashita to share his wartime experiences with students. Initially, he consistently refused. In his community, there were families who had lost fathers or sons in the war. “I don’t feel it’s right for me, who survived, to speak in front of others,” he thought. However, around 50 years after the war, he began sharing his experiences at elementary and junior high schools, coming to believe it was his duty as a survivor to convey what happened on the battlefield.

If only the war hadn’t occurred

For a long time after the war, Yamashita did not visit Okinawa. “My friends became part of the soil of Okinawa. I couldn’t bring myself to walk over them,” he said. However, he did end up visiting once. It was in 2007, when he attended a national conference in Okinawa hosted by the Japan Disabled Veterans Association (which disbanded in 2013) to receive a longevity award. “At night, I couldn’t sleep, remembering my war buddies,” he recalled.

In the Battle of Okinawa, not only soldiers but also many civilians lost their lives. The lesson learned from this, it was said, was that “the military does not protect civilians.” When this reporter relayed that to Yamashita, he responded emphatically, “How could we protect them? We couldn’t even survive ourselves. It was a living hell where you couldn’t move forward without stepping on corpses. Even if we wanted to protect them, there’s no way we could.”

Kazuaki Yamashita, who was sent as a soldier to the Battle of Okinawa and was shot in the ankle and arm, is pictured in Kunisaki, Oita Prefecture on Aug. 5, 2025. His war injury handbook notes “penetrating gunshot wounds.” (Mainichi/Takayasu Endo)

After the war Yamashita was blessed with three children, and he now has great-great-grandchildren. Reflecting on the war 80 years ago, in which lives were treated lightly, Yamashita said, “Why did we have to kill people? There was nothing good about it.” His eyes turned to the list of names of his friends who died as teenagers.

“There’s not even any remains of them. I wonder how they would have lived if there had been no war.”

(Japanese original by Masanori Hirakawa, Kyushu News Department)

Fewer than 1,000 now receiving military pensions in Japan

Eighty years since the end of World War II, the number of individuals who served on battlefields and other locations in the Japanese military during the Pacific War has dwindled significantly.

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, there is no comprehensive data on the number of surviving former soldiers, but as of fiscal 2024, there were 792 former military personnel receiving public “military pensions.” That year marked the first time since the system was reinstated in 1953, following its abolition after the war, that the number has fallen below 1,000. The figure represented a drop of over 40% compared to fiscal 2023, and is just 0.05% of the peak figure of approximately 1.39 million recorded in fiscal 1973. By age, 645 recipients are now aged 100 or older, accounting for over 80% of the total.

AloJapan.com