By Damian Flanagan

Recently, while doing a workout at home, I flicked around TV apps and came across a documentary on Netflix called “Salaryman” (2021). It might seem an odd thing to be watching while lifting a few weights and doing my sit ups.

The blurb for it didn’t sound promising. It described the Japanese salaryman as a “corporate drone” and I braced myself for some predictably broadbrush Western stereotypes of the Japanese. As someone with a high appreciation for Japan’s world-beating standards of service, their work ethic and dedication to professionalism, I rolled my eyes in anticipation of what misapprehensions this documentary was likely to contain.

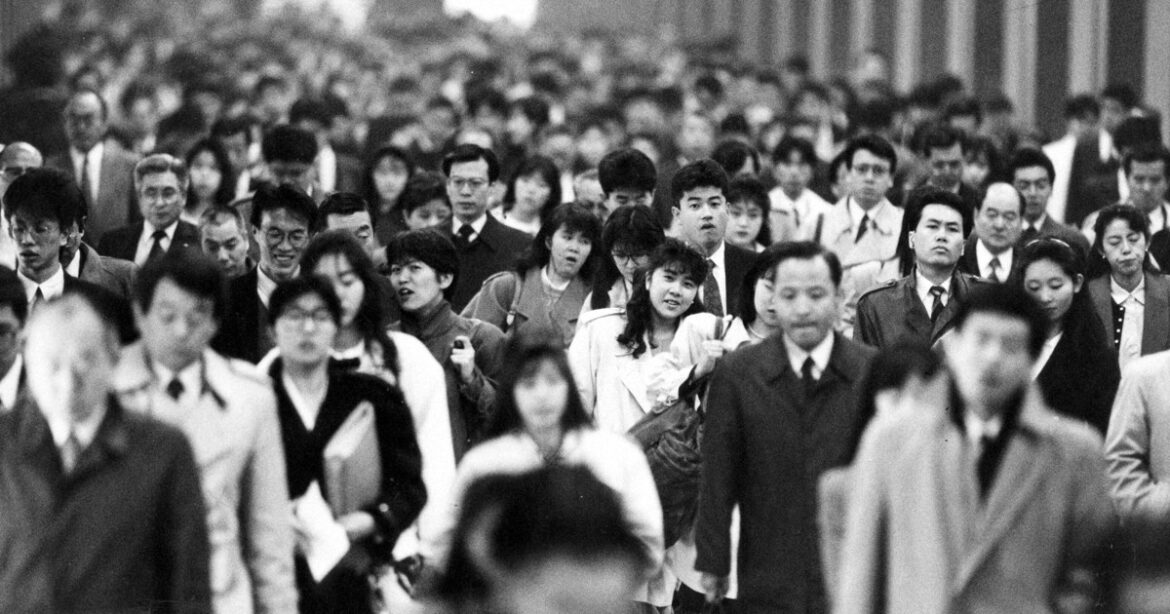

But, in fact, I could not have been more wrong: Allegra Pacheco’s documentary turned out to be highly insightful. Originally from Central America, she arrived in Japan having worked a stressful office job in the shark pool of New York and came to Tokyo observing with a fresh eye the millions of corporate workers that filled its rush hour trains and streets.

A cast of a sitting victim of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, 79 CE, Pompeii, Italy. (Public domain)

Her attention was particularly taken by the salarymen who collapsed drunk on the street after a night out quaffing with their colleagues and simply slept there, slumped in their crumpled suits. Pacheco traced around their bodies in chalk so that the white marks remained like murder scenes after they finally awoke the next morning to pick themselves up and return to the office. This was an astute signifier of lives wasted: Their chalked-around bodies were reminiscent of the bodies at Pompeii buried alive under the weight of some inescapable nightmare.

The salarymen Pacheco interviewed described daily routines where their individualities felt crushed under the weight of conformity to the corporations they were bonded to. One young salaryman described how he lived in a company dorm with a hundred other workers, woke up at the same time as them every day, showered at the same time as them, ate breakfast with them, took the train to the office with them, worked all day with them, then was obliged to socialize with his co-workers in the evening before going back to the dorm at midnight and then repeating everything again the next day. Some salarymen reported that they were lucky to have an hour to themselves every day and very little sense of their own identity outside of their workplace. Some salarymen with families described how they only saw their children two or three times a week and left all aspects of childcare to their wives.

These were, of course, the more extreme examples of the salaryman lifestyle — plenty of salarymen have far more balanced and contented lifestyles. And yet, anyone who lives in Japan has probably encountered at some time or other some salarymen caught up in these patterns.

A couple of drunken salarymen encountered by Pacheco outside a late-night bar optimistically described themselves as “Japanese businessmen”. But as other commentators in the documentary pointed out, the true businessman is irreplaceable. Many of these drudge salarymen seemed more easily replaceable, required only to fulfill a monotonous role. Some of the salarymen interviewed described themselves as “slaves”.

Buried inside some of these vassal salarymen were artistic dreams of other lives — one, realizing that his life was drawing to an end and that he had achieved nothing of what he had ever wanted to do, dropped out of the system altogether and went to live in a homeless encampment in a park and spent his days painting pictures.

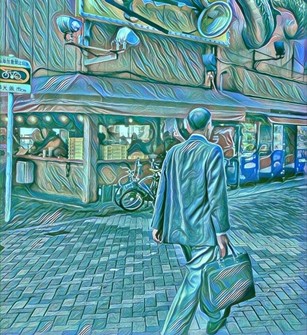

The existence and identity of some salarymen seems entirely subsumed within the confines of the company. (Image courtesy Karen McCann)

Watching a documentary about this made me think I had long since become normalized to the peculiarities of Japanese corporate culture. The salarymen were of course all around me in their hundreds and thousands, but they were not part of my world. I spent my time in Japan in universities and then in free-wheeling artistic pursuits. I had never worked as a salaryman, but the world of the salarymen has on a few occasions burst into my own existence.

Once, for a couple of months, I stayed in a homestay. The husband of the house was a salaryman for a computer company and had very little free time to spend with his family. It was, I observed, a source of ongoing discontent for his wife and a considerable source of familial tension. At one point, he went away for an extended period to work in another part of the country, leaving the home feeling bereft of a father figure.

Another time, I was putting out a book and worked closely with an editor at a publisher in Kyoto. This kindly man dedicated himself entirely to the company, even going to the library on his days off to look up obscure references on a manuscript we were working on. He was in late middle age, extremely well read and I once asked him if he had ever been to Europe. He told me yes, he certainly had. When I asked him where he had been, he elaborated that he had been there on a trip organized for the company employees — they had spent a total of two nights in Europe, he happily recalled, one night in London and one night in Paris, and then flown home again. His existence and identity seemed entirely subsumed within the confines of the company.

Pacheco is right that there can seem something tragic about the potential of lives sucked dry of individual freedom by the salarymen corporate structure. What exactly is it all for? Who in the end benefits from it?

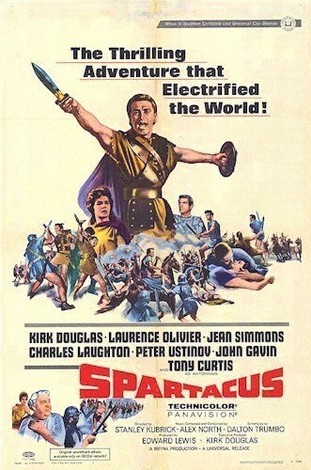

I mentioned to a friend the idea that some salarymen lived almost like slaves, but he chided me that even mentioning this was, for Americans in particular, a highly triggering subject, giving me pause. Yes, of course, no salaryman was a slave in physical chains, but since slavery was largely legally abolished around the world in the 19th century, great thinkers and artistic greats from Nietzsche, Sartre and Mill to Natsume Soseki and Bob Marley have continued to wrestle with the idea of “mental slavery”, whether to forms of religion or emotional attachments or outmoded social structures, that can still condition and confine us in various ways.

Damian Flanagan began to imagine slumped, unconscious figures of salarymen all suddenly awakening, standing up and proclaiming, “I am Spartacus!” (Public domain)

Looking at the images of the salarymen fallen down unconscious and sleeping on the street while being chalked around by Pacheco, you couldn’t help concluding that for some people the corporate system wasn’t working. I began to imagine these slumped figures all suddenly awakening simultaneously, standing up and proclaiming, “I am Spartacus!” and reclaiming their lives and freedom.

Japan benefits in so many ways from the dedication of the millions of men and women in the corporate world and the traditional systems of lifetime employment that look after them. But for some people, that world represents less a universe of career opportunities and more a place of mental confinement which they need to break out of in order to recover their human potential.

@DamianFlanagan

(This is Part 69 of a series)

In this column, Damian Flanagan, a researcher in Japanese literature, ponders about Japanese culture as he travels back and forth between Japan and Britain.

Profile:

Damian Flanagan is an author and critic born in Britain in 1969. He studied in Tokyo and Kyoto between 1989 and 1990 while a student at Cambridge University. He was engaged in research activities at Kobe University from 1993 through 1999. After taking the master’s and doctoral courses in Japanese literature, he earned a Ph.D. in 2000. He is now based in both Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture, and Manchester. He is the author of “Natsume Soseki: Superstar of World Literature” (Sekai Bungaku no superstar Natsume Soseki).

AloJapan.com