When did World War II end? Or, when will World War II end? This may seem a rhetorical question to most, with Aug. 15 marking the 80th anniversary of V-J Day (Victory Over Japan Day). On that date, Japan supposedly surrendered unconditionally. Few realize, however, that the state of war between the Allies and Japan did not legally end until years later with the Treaty of San Francisco, which was signed in September 1951 and took effect in 1952. That treaty did not include the Soviet Union, which attended but did not sign the agreement. The Soviets and Japan, through a joint declaration in 1956, reestablished diplomatic relations and ended hostilities, but to this date (and with Russia in the place of the Soviet Union) have never signed a peace treaty. Ongoing disputes, such as over the Kuril Islands, remain.

“Unconditional surrender” may have a ring of finality and totality to it, but in Japan it was never so. When Japan assented to the Potsdam Declaration, issued by the United States, United Kingdom, and China in July 1945, the terms called only for the surrender of the armed forces, and for some parts of the country to be occupied. As Richard Overy describes in his new book, Rain of Ruin, the Japanese emperor’s address on Aug. 15, 1945, did not even include the word “surrender.” Two days after V-J Day, when the Japanese were still lobbying to avoid having mainland Japan occupied in its entirety and protesting having to turn over their overseas embassies to the United States, it was clear their interpretation of Potsdam differed from that of the Americans. Meanwhile, in Manchuria, the Kuril Islands, and elsewhere, Japan continued fighting against the Soviets until as late as Sept. 5.

In 1945, a shell-shocked Japan did as it was told, and in many ways, it is still keeping counsel. There are a few reasons for this ongoing silence, including to do with how the United States treated Japan afterwards. During the occupation (September 1945 to April 1952), Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur’s administration instituted sweeping reforms that have mostly proven to have been wise. (For instance, there has never been an amendment to Japan’s Constitution, which was introduced in 1946 and is sometimes called the “Peace Constitution”—or the “MacArthur Constitution.”) But in keeping with the American penchant for moving on and dispensing with the past, they also tended to let the country off the hook.

Officials in suits and top hats and others in military uniforms stand on the deck of a ship. U.S. men in uniform stand in the background.

Japanese officials on board the USS Missouri during surrender ceremonies in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, 1945. Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

MacArthur set the tone early, on Sept. 2, aboard the USS Missouri: “The issues involving divergent ideals and ideologies have been determined on the battlefields of the world and hence are not for our discussion or debate.” As social theorist John Lie has pointed out, by dictating the constitution in order to create the “Switzerland of Asia,” the United States in essence absolved Japan from having to do any independent soul-searching of its own. The Tokyo War Crimes Trial (1946 to 1948)—officially the International Military Tribunal for the Far East—was unsatisfying even to some key figures among the prosecuting Allies, and within Japan opinions of it remain a bellwether of one’s political views. This stands in sharp contrast to the Nuremberg trials, about which few people seriously doubt the legitimacy, motives, or the verdicts.

In the decades after the war, there was no flood of memoirs from returning servicemen, in part due to a sense of shame. The U.S. occupation apparatus included the Civil Censorship Detachment, which reviewed and heavily redacted all books, magazines, newspapers, film scripts, music lyrics, phonograph records, and mail, on the lookout for anything that might even distantly be construed as celebrating or discussing the recent war or government. Discussing censorship in the media was itself censored. For most Japanese citizens, this was business as usual, and even a lighter touch than recent experience: From the early 1930s through 1945, Japan had lived under an increasingly militarized and repressive regime, with severe punishment for anyone who stepped out of line.

There was another reason Japan could not simply move on. In August 1945, there were some 6.5 million Japanese soldiers, sailors, and civilians overseas. Most needed repatriation to a country that had just lost a world war and imploded domestically. As well as Japanese prisoners dotted in garrisons on Pacific islands, there were large units in China, the Philippines, and in places throughout Asia where European colonial powers were busy trying to reclaim their empires. Japanese POWs were in Southeast Asia until October 1947.

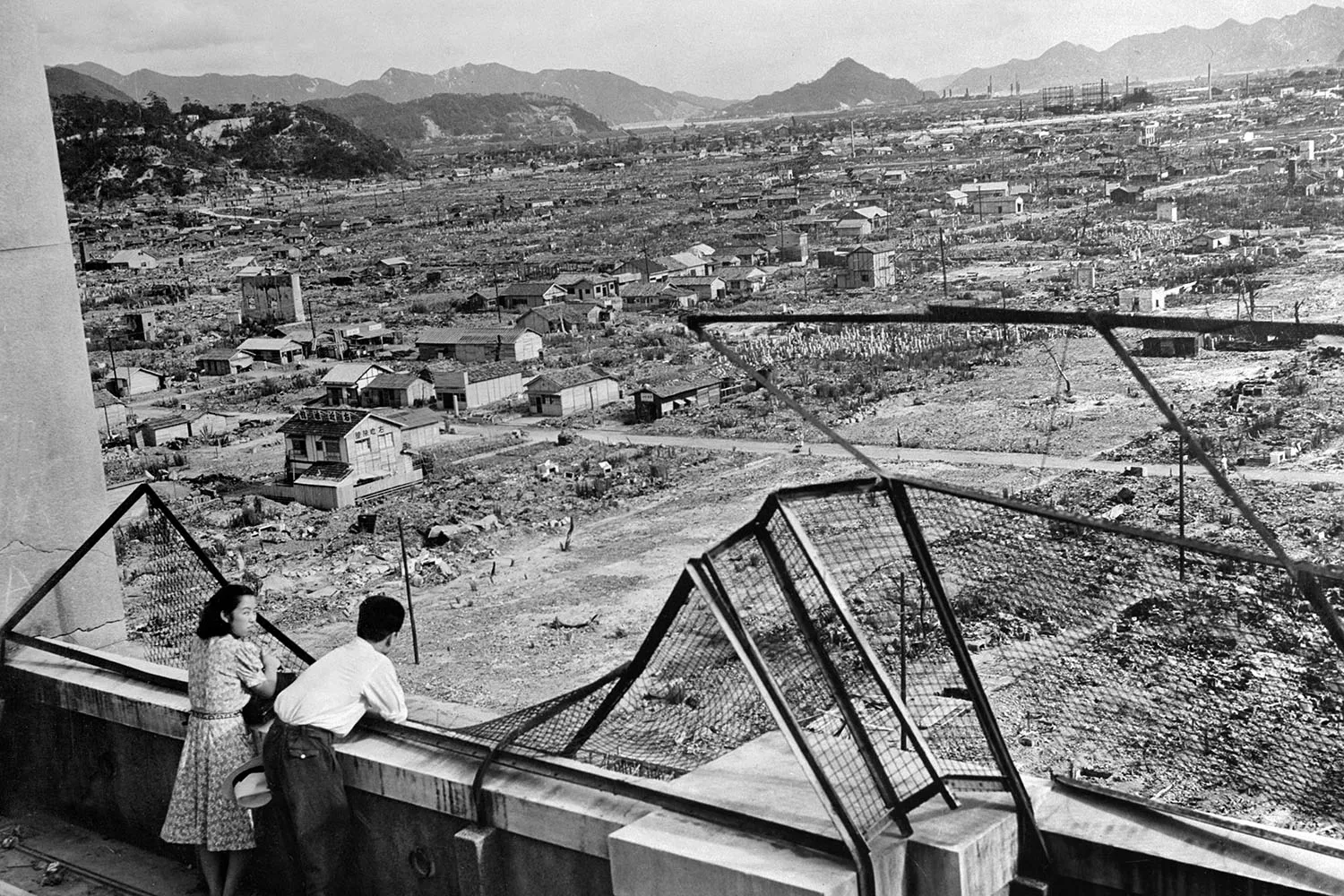

Two people stand on a ledge overlooking the grid of a city with the debris of demolished buildings stretching to the horizon.

The devastated landscape of Hiroshima in 1948, three years after the U.S. bombing laid waste to the city.AFP via Getty Images

At home, the cities were wastelands, with citizens undernourished and diseases like tuberculosis rampant. Hunger and starvation lasted for years; the average height and weight of elementary school children decreased until 1948. In 1947, a 16-year-old Shirley Hazzard, later a famed novelist who featured Hiroshima in two of her most important works (The Transit of Venus and The Great Fire) traveled with her parents from her home in Australia to Kure and Hiroshima, and then on to Hong Kong. Her liner sailed into one of the main bases of the Imperial Japanese Navy: “And then we came into Kure, and it was just full of sunken ships, lopsided, capsized.” Japan seemed stuck in the war, she noted, while she later found bustling Hong Kong had already moved on—the war there “a lingering memory rather than a palpable presence.”

Or consider people of Japanese ancestry living in Brazil. In the early 20th century, overpopulation and rural poverty in Japan (as well as discriminatory anti-immigration laws in the United States) prompted Japanese citizens to look toward Latin America; 183,000 emigrated to Brazil alone. For these emigres in 1945, the belief lingered that Japan was winning the war, even after the surrender. Militant “convictionists” (vitoristas or shinnen-ha) rejected news of the defeat and instead launched terrorist attacks against “recognitionists” (esclarecidos or ninshiki-ha), Japanese Brazilians trying to inform the community of Japan’s defeat. Recognitionist leaders were killed. The turmoil lasted for years: In the early 1950s, swindlers were at work persuading migrants to sell their property to them under the false pretense that the victorious Japanese government was sending ships to Brazil to pick them up and repatriate them.

As many as 1.3 million Japanese soldiers and civilians surrendered to the USSR only to endure years in captivity. Perhaps a quarter of a million died after the war in Soviet labor camps. The naval dockyard at Maizuru on the Sea of Japan acted as the main port of reentry for returnees from Siberia, and from 1945 to 1958 some 346 ships arrived carrying more than 650,000 . Hearing rumor that a ship might be arriving, people from across the country would trek to Maizuru to see if a family member was aboard.

Contrast the somber, emotional scenes at Maizuru with what was happening in the United States in the mid-1950s. The war was in the distant past, the infrastructure and routines of modern life that persist to this day had already been established: The first suburbs had been built, as well as the first indoor shopping mall. Dwight Eisenhower’s massive interstate highway construction program, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, was set to transform how Americans got around. The United States was already onto the suburban ennui of Revolutionary Road while Japan was stuck in Tales of the South Pacific.

Sengo is the Japanese term to describe “after a war.” It’s no wonder that the government did not finally declare the end of the sengo until 1956.

The war also stayed fresh (but on ice) in Japan even decades after the occupation was over, in part because soldiers who had never surrendered were still wandering in from the far reaches of empire. They included Yokoi Shoichi, discovered still armed and fishing in Guam in January 1972, who re-affirmed his belief in the emperor and credited his survival to “believing in the Yamato spirits.” In Japan, these episodes made front-page news and the mostly low-level soldiers were celebrated, whereas in the immediate postwar period veterans had been shunned. Their stories, safely apolitical, also harkened to Japanese wartime feature films, hugely popular, many of which had focused on the drudgery of plucky infantry soldiers rather than on the generals and their strategic conquests.

There is not even an agreed-upon way of referring to the events in Japan between 1931 and 1945. Naming the conflict would seem to be a necessary first step to dealing with it. Without it, the story feels still open to interpretation. Earlier this year, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba said he would convene a panel to finally get to the bottom of why Japan plunged itself into a “reckless war” and why the government of the day was unable to rein in the military. Findings were originally slated to be released in time for the Aug. 15 anniversary. They have now been delayed.

But a 50-year-old anime film may be helping the Japanese find closure on 80-year-old events.

A smoking battleship is seen from above as planes fly over.

The Japanese battleship Yamato burns while under attack from U.S. planes off Kyushu, Japan, on April 7, 1945.Corbis via Getty Images

The original Yamato was the heaviest, most powerful battleship ever built. It was constructed in secret, and during the war, officers aboard did not even know the size of the ship’s guns. Some 380 planes from U.S. aircraft carriers sank Yamato while it was on a suicide mission to Okinawa in April 1945. The ship exploded in a huge mushroom cloud that resembled—and anticipated by just a few months—what would transpire at Hiroshima. After the war, U.S. censors prohibited Japanese from writing about Yamato, which makes its second life as a creative font all the more stunning.

The premise of Space Battleship Yamato, a TV series that premiered in 1974, is that in the year 2199, the Imperial Japanese Navy battleship is raised from where the Americans sank it in 1945. It is refitted (but recognizable as the wartime ship) and flown to outer space to take on an alien race, the Gamilas, and bring back radiation-cleaning equipment to sanitize a contaminated Earth.

Since the initial TV show, the story has rarely been out of production; there are several feature-length anime movies in the works right now. In the 50 years since its release, the franchise has become hugely influential among Japanese creatives and is considered by some the starting point for otaku (obsessed fandom) sub-culture. It has also become a literal and metaphoric vessel for exploring Japan’s war baggage.

As I found while researching my book The Cult of the Yamato, the ship itself has a simultaneous grip on both memory and imagination. It has featured in literature, painting, film, anime, manga. It has a large, dedicated museum in Kure, near Hiroshima, annual attendance at which rivals that of the most popular warship museums in the world—but in Yamato’s case, there is no warship present. To some, it represents the apogee of Japan’s industrialization from the Meiji Restoration onwards, in a race to catch up, technologically and in empire-building terms, to the West. Quietly, many Japanese take pride in the skills and resources it took to build the ship—that it could be birthed from their country, which was thought at the time to be backwards. They point out that many of the innovations that went into her construction were critical to Japan’s postwar economic prosperity, a familiar narrative known as “the fortunate fall.”

An actor in a uniform with helmet and red circle on it stands next to other actors in military uniforms.

Actors in military uniforms perform aboard a reproduction of the Yamato during the filming of Yamato for Men in Onomichi, Japan, on June 3, 2005.Koichi Kamoshida / Getty Images

A recurring plotline for the fictional spaceship Yamato involves it engaging in near-suicidal maneuvers to break through alien blockades, symbolizing for some a recreation of the actual Yamato’s attempt to steam through assembled U.S. naval forces and arrive to save Okinawa. Susan Napier, now a professor of cultural studies at Tufts University, wrote in 2005 that the fictional ship’s movements can be seen in psychoanalytic terms as “plunges into the collective unconscious of the postwar Japanese citizenry, a form of ‘working through’ the collective national trauma of defeat.” Napier calls the films “a form of cultural therapy.”

Why rely on pop culture to explore this loss? Because the usual disciplines or avenues are foreclosed or clogged. Trained historians in Japan are often marginalized. “The thing is, as soon as you bring historians in, you run into problems, you get distortions,” a young Shinto priest at the conservative Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo told Ian Buruma more than 30 years ago. Bookstores are almost devoid of history sections touching on the war. Japan’s school textbooks are bland, opaque, dissembling about the war, belying the bitter debates that take place behind the scenes to arrive at such spent tepidness. And, ironically, the part of Japanese society perhaps most formally sealed off from World War II and its legacy is the present-day military, the Self-Defense Forces. The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), essentially Japan’s navy, takes no interest in the Yamato. The several expeditions to the shipwreck that have taken place have had no JMSDF or government involvement, and no official public statements on them have been issued.

In response, Japanese pop culture has picked up the slack, and artifacts like the Yamato are freighted with significance. In a 2019 feature film about the real Yamato, titled The Great War of Archimedes, the final scene sees the tearful main character, a pacifist naval architect, gaze out as Yamato sails away, alone. A colleague enquires why he is crying. “That ship is Japan itself,” he responds.

Men in uniforms wearing large ribbon rosettes pinned to their chests bow their heads.

Surviving crew members of the Yamato and descendants of its crew attend a memorial service in Kure, Japan, on April 7, 2015, on the 70th anniversary of the ship’s sinking. Jiji Press/AFP via Getty Images

“For the Japanese people, there is no greater icon of the Pacific War than Yamato,” said director Takashi Yamazaki, who wrote and directed Godzilla Minus One and previously made two films about the Yamato, in a 2015 interview. “In Space Battleship Yamato, there is a deep-seated grudge about IJN Yamato, and the desire for a dream that could not be fulfilled.”

In Kantai Collection (usually abbreviated to KanColle), a popular multimedia franchise, the ships of the wartime Imperial Japanese Navy are transformed into students at an all-girls boarding school. (It is one of several franchises to make a similar transfiguration of ships into female form.) Yamato is portrayed as tall, buxom, regal, with flowing dark hair usually tied in a ponytail. She carries a parasol, meant to represent her mainmast. Her turrets are arrayed along and from her arms. Shells for the massive 18.1-inch guns are kept in garter belts at her thighs.

Matt Alt has described the Japanese sense of play that underpins the “cool Japan” brand identity as manifesting in “fantasy-delivery devices” like the karaoke machine, emoji, Nintendo, Hello Kitty, Pokémon, etc. (“Cool Japan” also happens to yield the country huge soft power gains.) Japanese manga and anime artists, as well as game developers, have anthropomorphized all manner of objects into girls and young women; why not a 64,000-ton steel dreadnought?

By 2016, the game version of KanColle, which is only available in Japanese, had 4 million registered users. The anime version is laced with clever and factually accurate Easter eggs related to the war, though the game’s manufacturers, fans, and players take great pains to explain that KanColle lives in an alternate reality with the action taking place decades after the war, not during it.

A crowd of people in coats and hats walk off a ship as they arrive in a port.

Japanese people repatriated from Siberia are welcomed on arrival at the port in Maizuru, Japan, on March 20, 1954.The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images

The lines between make-believe and the real world are blurred, though. Take the aforementioned Maizuru, which because of KanColle is one of the “sacred sites” of anime. The Victorian-looking red-brick buildings of the dockyard regularly host events at which cosplaying women outfitted as Japanese wartime warships, as well as their boisterous fan bases, mingle with family members making somber return visits to the site where their relatives were repatriated from Siberia. Mixed in are tourists come to see the modern JMSDF naval base or visit the sleek Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum.

Incidents like these highlight the confusion between fictional, commercial, and entertainment-driven representations of the war, which in some ways are divorced from the true nature of the war as experienced by many Japanese. Japan has not been to war since 1945, and some scholars see the country as culturally and emotionally removed from the realities of war. In 2005’s live-action film Yamato, present-day boat skipper is Kamio is without a wife or children, reclusive, and traumatized; Makiko, the younger female lead, is an orphan, adopted by Kamio’s fellow Yamato crewmember Uchida, who was presumably rendered sterile by the war. This is contrasted, in a series of flashbacks, with the brave physicality of Yamato’s crew during the war. The message, as Yale film historian Aaron Gerow has written, is that Japan was more virile and had more agency and independence before and during the war than after it. Though subtly delivered, it is a daring message for a country where the word “peace” is practically punctuation, and where virtually everyone professes to revile all aspects of the fascist government and imperialist past.

Gerow says the power of the film went well beyond its commercial success: “Yamato was in some ways a traumatic film for spectators, too. Viewer comments on Yahoo Japan and other sites often describe the difficulty of speaking or communicating after the film, as if aphasia was one of its effects.” The specific image of the battleship Yamato in such films, according to researcher Kaori Yoshida, is premised on “a masculine symbol of the ‘unsinkable’ nation.”

Doves take flight from the outstretched hands of a crowd of people.

White doves are released as a tribute to the war dead at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo on Aug. 15, 2024. Tomohiro Ohsumi/Getty Images

In August 1945, Japan lost not just the war but a sense of self. It could no longer adhere to the narrative that it was a great power. Decades of hard work had led to the country believing it had made a place for itself in the world—at a minimum, that it was a model and leader for Asia. In retrospect this seems misguided, but no more so (nor no more egotistical) than manifest destiny.

Japan was on a war footing from the early 1930s onward. Couple this with the nearly seven years of post-conflict occupation, and it’s clear that Japan’s war has always defied the neat delineation of 1939 to 1945. Within hours of the San Francisco Treaty being signed in 1951, another agreement was made: the Security Treaty between the United States and Japan. To this day, the shorthand for describing the bilateral defense partnership is the U.S. spear and the Japanese shield, a pretty clear male-female dyad. And in much of the pop culture outputs alluding to the war, there is an underlying ambivalence about the United States. It is the lurking force in Space Battleship Yamato, Godzilla, Kantai Collection, Silent Service, and other franchises. Blame for Japan’s defeat and subsequent diminution is assigned in equal parts to the domestic government of the time and on the Americans who, beginning with Matthew C. Perry in 1853, demanded entry and also that Japan re-invent itself.

In the early postwar period Japan had neither the time nor energy to want to plumb its thoughts on the war. Time passed; facts and history that had perhaps at first been bound in temporary bandages were now mummified. They remain unresolved, unsolvable matters of interpretation, emphasis, or partisanship; some events are claimed not to have taken place at all. Japan has had a decades-long head start in contending with cherry-picked facts, disinformation, misdirection, dog whistles, and information silos. In 2025, it is a story relevant to all of us. And so the war drags on.

AloJapan.com