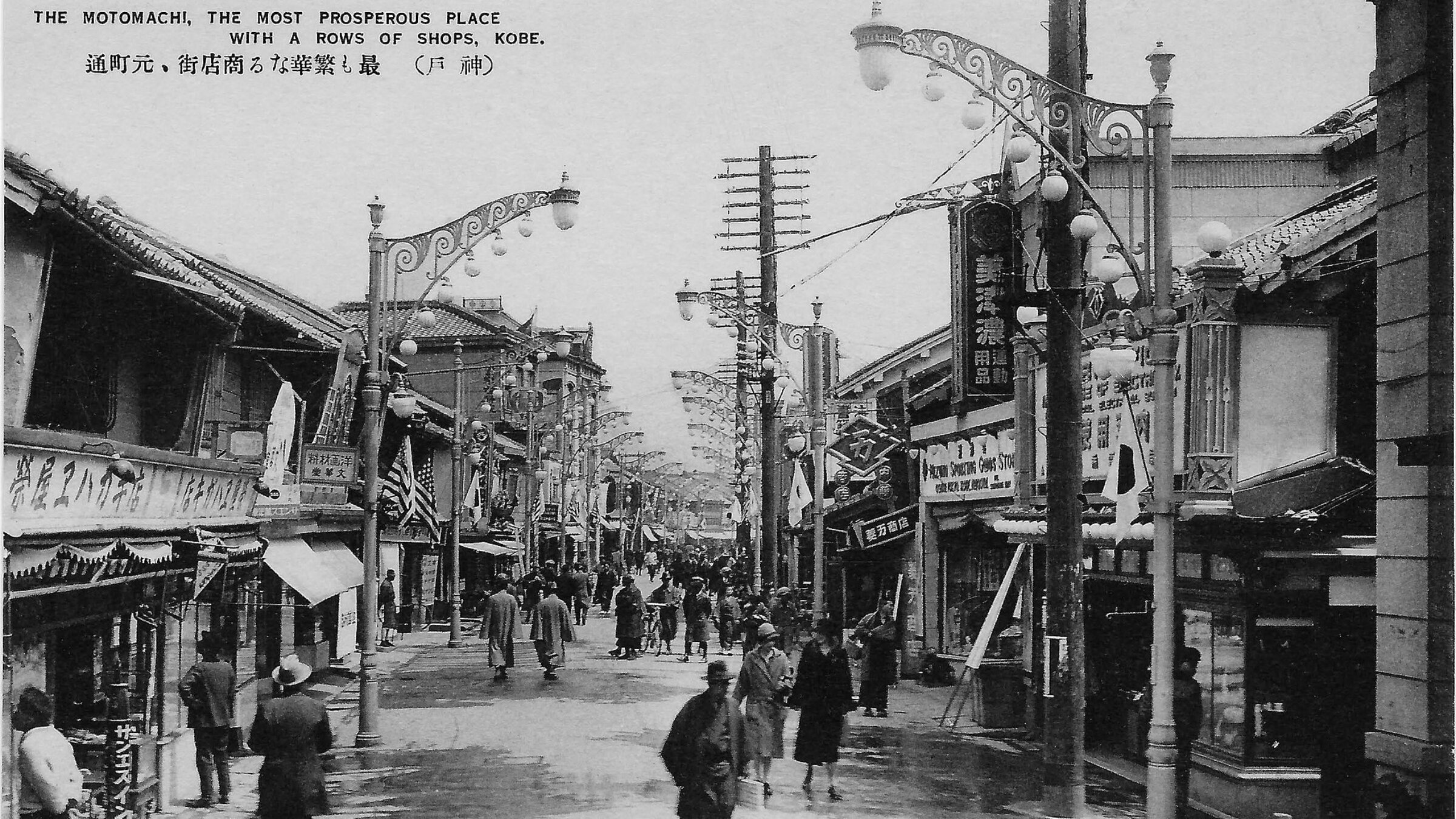

A Japanese postcard of a street in Kobe, Japan, taken before World War II (author unknown) Photo by Wikimedia Commons

By Jennifer A. Stern

August 13, 2025

Exactly 85 years ago — in August, 1940, a year after the beginning of World War II — 30-year-old Meyer Zucker received a visa from the Japanese consulate in Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania. It allowed him to leave Europe and spend eight months in Japan, away from the murderous onslaught of Nazism, almost certainly saving his life.

Zucker didn’t realize until years later that the man who signed his visa was Chiune Sugihara. Sugihara risked his career giving out over 2,000 visas to desperate Jews in Kovno in July and August 1940.

Today, Sugihara is honored in Japan and around the world for his courage and humanity; Yad Vashem recognized him in 1985 as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. But at the time, his decision to give visas to Jewish refugees was frowned upon.

Most of the fleeing Jews lacked the money and documentation they’d need to leave Japan once they arrived, meaning they would have to stay there — a situation that the government in Tokyo wanted to avoid. Yet despite repeated warnings from his bosses, Sugihara gave these Jews visas anyway. After the war, he was removed from the diplomatic service. His career never recovered.

The Jews he helped escape to Japan were plunged into an unfamiliar culture in a country they never expected to visit. Meyer Zucker’s experiences, described to me by his daughter, Yiddish literature scholar Sheva Zucker, give insight into this meeting of worlds — and the lives that Sugihara saved.

* * * * *

Stern: What was your father’s situation in August 1940 when he received his visa?

Zucker: He fled Warsaw after the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939. He and some friends from the Jewish Labor Bund became refugees in Lithuania. Of course they knew what was happening to Jews in Poland, and dreaded a Nazi invasion of Lithuania too.

When the Soviets annexed Lithuania in August 1940, my father and the other Bundists knew they might be arrested, since the Bund was socialist and anti-communist. They traveled to Kovno, the capital where all the foreign consulates were, and heard that the Japanese consulate was giving visas to Jews.

Stern: How did your father get to Japan?

Zucker: He went by the Trans-Siberian Railway from Moscow to Vladivostok. Fortunately, the Soviets didn’t interfere with Jews who had visas to Japan. It took time for him to arrange his travel and make the long train journey. So he sailed from Vladivostok to Japan in February 1941.

Stern: What were his first impressions of Japan?

Zucker: He was charmed by the little houses near the shore that he could see from the ship. He’d just crossed Siberia in winter, but spring was starting in Tsuruga, the port where they docked. Everything looked fresh and green, like a promised land.

The refugees were in Tsuruga for at most a few days. I wrote in the Yiddish Forverts about my recent visit to Tsuruga, where the Port of Humanity Museum (opened in 2008) suggests the mutual curiosity that Japanese and Jews felt about each other. There were some culture clashes — the Japanese were surprised that Jews would eat while walking in the street, which they considered impolite. But most Japanese were welcoming and sympathetic.

Stern: Where did your father go next?

Zucker: After their short stay in Tsuruga, the Jewish refugees were sent to Kobe, near Kyoto. There was a small but historic Jewish community in Kobe, which called itself JEWCOM. The community leapt into action to assist the refugees, helping them find food and housing and giving them advice and support. My father described living with other Bundist friends, probably in a hostel sponsored by JEWCOM. Jewish refugees also received financial support from the Joint Distribution Committee, which coordinated with JEWCOM. The local Japanese community was very supportive of the Jewish refugees.

Stern: What was your father’s life like in Japan?

Zucker: The refugees weren’t allowed to work. My father spent a lot of time sending food back to his family near Lublin in Poland. He knew that their circumstances were very difficult and they probably didn’t have enough to eat. He sent them tea, biscuits — all kinds of small items that weren’t too expensive to ship. He got appreciative letters back from his sister.

Meyer Zucker (far left) and his other refugee friends visit the Nara pagoda Courtesy of Sheva Zucker

Meyer Zucker (far left) and his other refugee friends visit the Nara pagoda Courtesy of Sheva Zucker

My father was curious about his new surroundings. He and his Bundist friends visited Kyoto, and the Buddhist temples at Nara. I have a wonderful photo of a group near the pagoda in Nara, with the famous temple deer. They went further afield to Tokyo, too. They wanted to see as much as they could.

Stern: Why did your father leave Japan after eight months?

Zucker: It wasn’t by choice. By the summer of 1941, Japan had become an Axis Power, meaning they were allied with Nazi Germany. Japan decided to relocate its Jewish refugees to Shanghai, China — a city that Japan controlled. Life in Shanghai was much harder than in Kobe, especially after the Shanghai Ghetto was established. My father stayed there until early 1948, when he finally got a visa to Winnipeg in Canada, where he had family. That’s where I grew up.

Stern: Did your father talk to you about Japan while you were growing up?

Zucker: Yes, frequently, but not in an organized way. Most of the details came later, when he narrated his memoirs to me in Yiddish before he died in 1987. I translated them into English. But I always knew that Japan was a very special place for him — the place that saved his life.

Aya Takahashi, a Japanese-Canadian journalist who writes extensively on Sugihara, contributed to this article.

AloJapan.com