Walking from Shibuya to Meguro on Tokyo’s Yamanote loop, the city quiets down. You leave behind architectural chaos, neon and noise, trading them for sloping streets, cozy cafés, and leafy streets. Yebisu Garden Place’s mix of culture, fine dining, and shopping is gradually replaced by the secluded residences of the Tokyo elite.

Starting Out from Shibuya

One station is as good as another when it comes to starting a walk along Tokyo’s Yamanote Line. Today I have chosen to head counterclockwise from Shibuya, one of the loop’s main stops. In order to go south, I need to cross National Route 246, a 125-kilometer-long monster of a highway from Tokyo’s central Chiyoda district to Numazu, Shizuoka, where the constant roar and rubbery thumping sounds of traffic never end. I briefly stop on the overpass to look back at the local skyline. Shibuya’s horizon has narrowed in the last few years, hemmed in on all sides by new high-rises—the Hikarie complex, Shibuya Stream, Scramble Square, and Fukuras—looming over the station like glass sentinels. In the distance, the yellow convoy of the Tokyo Metro Ginza Line enters the station. This is a rare opportunity to see the Tokyo subway emerge from underground.

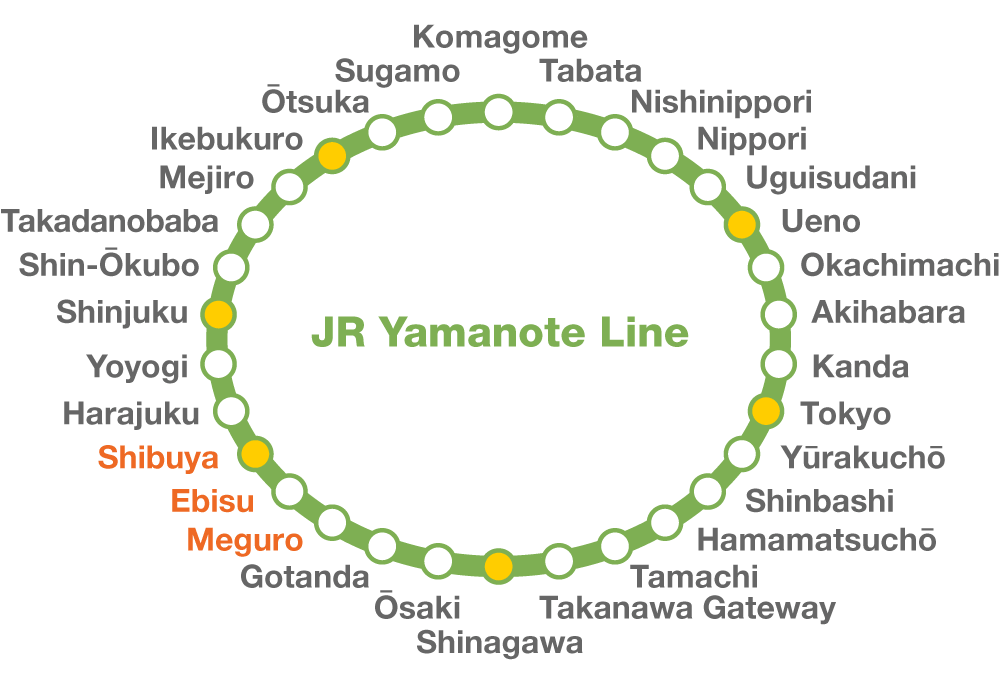

The stations on the Yamanote line stations loop. (© Pixta)

The fifth and youngest piece in the new architectural puzzle stands just south of the station. Sakura Stage occupies a 2.6-hectare site and consists of two buildings, respectively 39 and 30 floors high, connected by a deck. Like the other buildings, it will include offices and commercial stores (with workspaces for up to 10,000 people) as well as residences and serviced apartments for medium- to long-term stays.

Sakura Stage was built in Sakuragaoka-chō, atop one of the hills surrounding Shibuya Station. Until the end of the Pacific War, one of these narrow winding slopes led to the Naka-Shibuya Church, part of the United Church of Christ in Japan, which is the largest Protestant denomination in the country.

The church’s major claim to fame, so to speak, is its appearance in the 1964 film Black Sun. By that time, it was falling to pieces and cut a stark, eerie figure amid the bustling new city reborn after the war. The film portrays the complex relationship between a jazz-obsessed Japanese drifter and thief who lives in the church and an African-American soldier on the run from the police, and the place serves as a significant backdrop, symbolizing the cultural and emotional intersections between the two men, underscoring themes of alienation, redemption, and the search for connection in postwar Japan.

The building we see in the film was erected in 1917 by Pastor Mori Akira. He was the third son of Mori Arinori, Japan’s first minister of education, who was stabbed to death by an ultranationalist in 1889. The original church is long gone, having been demolished during the filming of Black Sun. Its latest version, completed in 2020, can be found not far from there.

Getting away from the high-rises and following the southbound Yamanote tracks, I find myself in a completely different world made of old dilapidated buildings decorated with graffiti and stickers. It also seems to be the favorite route of the few joggers who dare run around this part of the city squeezed between the ubiquitous construction sites, rusting railways overpasses, and the trains rattling on the other side of the fence. They rush by every minute, sometimes even every 15 or 20 seconds.

The area south of Shibuya is full of old buildings decorated with graffiti and stickers. (© Gianni Simone)

A few people can be seen jogging between under the rusting railway overpasses. (© Gianni Simone)

Creative Chaos in the Tokyo Cityscape

Gazing across the railway tracks, one gets a crash course in Tokyo’s approach to urban planning, its rules and regulations. In short, there are none.

It’s a free-for-all of architecture: boxy apartments beside Art Deco leftovers, next to minimalist cubes or riotously tiled façades. Buildings huddle shoulder to shoulder with only the barest of space separating them. There’s probably a height limit, but beyond that, it’s creative chaos. Want a lime green house next to a faux-European café topped with faux-Greek columns? Go ahead. In this city, zoning feels more like a suggestion than a system, and uniformity is someone else’s problem.

Tokyo’s architecture is, to put it mildly, wildly eclectic. Its apparent lack of a unified style gives the city an uncanny, almost otherworldly character, like the retro-futuristic landscapes imagined in science-fiction films like Blade Runner: a vision of the future that feels both posthistorical and poststylistic, inhabited by chaotic, hybrid forms. Tokyo’s cityscape seems to exist outside of time, both archaic and futuristic in equal measure. This layered mix of architectural eras and impulses evokes, for me, a dystopian future teeming with survivors of some catastrophe.

Tokyo’s architecture is, to put it mildly, wildly eclectic. (© Gianni Simone)

To heighten the surreal contrast and add a certain frisson, they added an incineration plant just across the tracks and a 15-minute walk from Shibuya’s famous scramble crossing. This is one of 21 facilities located in Tokyo’s 23 central cities. Several are tucked away on the manmade islands cluttering Tokyo Bay, while at least two more—one between Ebisu and Meguro and another one next to Ikebukuro—sit surprisingly close to Yamanote Line stations.

The Shibuya plant can process about 200 tons per day of waste and is equipped with air pollution control to reduce the concentration of dioxins, heavy metals, and particulates released after incineration. Apparently, Japan’s facilities are considered among the safest and cleanest in the world. They produce far below WHO-recommended dioxin levels, are rigorously maintained and upgraded, and use negative air pressure systems to prevent bad smells from escaping.

Bathrooms, Beer, and More

When I get to Ebisu, I take a quick bathroom break. Ebisu is, among other things, at the avant-garde in this particular category, being one of the locations of the Tokyo Toilet Project—a set of 17 public toilets created by famous architects and designers like Kuma Kengo and Pritzker Prize winners such as Andō Tadao, Ban Shigeru, Itō Toyoo, and Maki Fumihiko. Four of them are very close to Ebisu Station.

Tamura Nao designed one of the public restrooms for the Tokyo Toilet Project. (© Gianni Simone)

Granted, these 17 designer loos are just a drop in the ocean of Tokyo public toilets. Shibuya Ward alone has 186 standalone (street/park) facilities, or about 12.3 per square kilometer. The 23 central municipalities average around eight per square kilometer (for comparison, Paris has 6.7). Also, Tokyo has approximately 53 standalone public toilets per 100,000 residents, compared to London’s 14.

Ebisu embodies the polished, entitled spirit of western Tokyo’s residents—people with delicate sensibilities, deep pockets, and sophisticated tastes—so it makes perfect sense to approach its most prominent shopping and cultural complex through a convenient, weather-protected, 400-meter-long moving walkway.

When you finally reach the end of the walkway, Yebisu Garden Place, you know you are not in Shibuya anymore: open spaces, wide avenues, and lots of trees—at least by Tokyo standards.

Yebisu Garden Place is a stylish urban complex combining offices, shops, restaurants, a museum, and a scenic plaza. (© Gianni Simone)

A gently sloped promenade leads to a spacious central plaza crowned by a sweeping glass arch. Dominating the scene is Château Restaurant Joël Robuchon, a replica of a Louis XVI French palace housing three Michelin-starred restaurants. Curiously, I’ve never seen a soul venture inside the faux-château.

And to think that Ebisu had much humbler origins. Yebisu Garden Place was once the site of the Dainippon Beer Brewery, the predecessor of Sapporo Beer, and the name of both the station and the district—minus the Y, which comes from older orthography in the language—come from one of Japan’s oldest beer brands. The station itself started in 1901 as a freight-only station for shipping beer. The passenger service began in 1906 (the same year when the Japanese railways were nationalized) but it was mainly used by the factory employees to commute to work. Finally, Ebisu Station was incorporated into the Yamanote Line in 1909.

Quiet Opulence on the Way to Meguro

As it often happens around the Yamanote Line, the railway divides Tokyo in two very different environments. Between Ebisu and Meguro, for instance, the outer side is the commercial district, with lots of affordable shops and restaurants, while the inner side is a zone of quiet affluence, where the signs of wealth are understated but absolute.

Ebisu and Kami-Ōsaki are avidly sought by upper-class residents, as they combine a central location and access to upscale retail and fine dining with a refined atmosphere, discretion, and privacy.

Ebisu is the home of affluent singles, power couples, foreign executives, and creative professionals who live in elegant tower condos like the Parkhouse Ebisu and luxury low-rise apartments. Modern 2-bedroom apartments in new luxury towers range from ¥700,000 to ¥1.5 million a month.

High living in the high rises of Ebisu. (© Pixta)

However, even the Ebisu tribe of young, gym-toned, upwardly mobile creatives and tech-world climbers who like to gather over third-wave coffee and natural wine can only dream of living in Kami-Ōsaki. Here’s where people who already have everything choose to live. Wealthy Japanese families, corporate executives, some patrician households—this cloistered elite, Tokyo’s “whispering aristocracy,” has low visibility but high prestige. In a world increasingly ruled by the showy and tacky rich, Kami-Ōsaki is one of those areas where wealth does not roar. It glides in leather-soled silence behind wrought-iron or black metal gates, high hedges, and stone walls.

There are no high-street commercial zones around here, but rather embassies, exclusive schools, and historical estates. Detached homes can exceed ¥2 billion in price, and rentals often aren’t even publicly listed, being handled via off-market private agents.

Strolling around these extremely quiet and discreet streets, I feel like I’ve fallen into a wormhole and been transported to a parallel universe. Grand houses—real mansions, not the run-of-the-mill Japanese manshon (condos)—dispose themselves along a golden road. Gravel drives lie behind ironwork gates on which closed-circuit security cameras replace heraldic beasts. High-end imported cars are everywhere. One of them slips silently past me along a sakura-lined hill. You won’t find this neighborhood on tourist maps. That’s exactly why old money lives here.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Ebisu Garden Place, just southwest of Ebisu Station. © Pixta.)

AloJapan.com