Where are you from? Has always been a deceptively complex question for me. The short answer that people are looking for is America. The long answer is I was born in America, raised in Japan, spent another stint in America, then Kenya, before permanently returning to Japan, realizing it was home. So, where am I from? It depends on what you mean by from.

Living in Japan’s countryside, I have a conversation in Japanese almost daily that goes something like this:

Me: Hello, are you open?

Them: Oh, your Japanese is fluent!

Me: Thank you, I’m just learning, haha (the requisite humility). Actually, I grew up here and attended Japanese school. I’ve been here most of my life.

Them: Oh, you are Japanese then!

Me: I know, people tell me I look Japanese (They laugh because I’m as American-looking as it gets).

On the other hand, Americans who have heard about the challenges of integrating into Japanese society often ask me about my identity and acceptance in Japan. Do you feel more Japanese or American? Do they treat you like a local or a foreigner over there? Will you ever be fully accepted? Were you bullied for being different? These are all common concerns.

I was reminded of the issue’s complexity during a conversation with my mother.

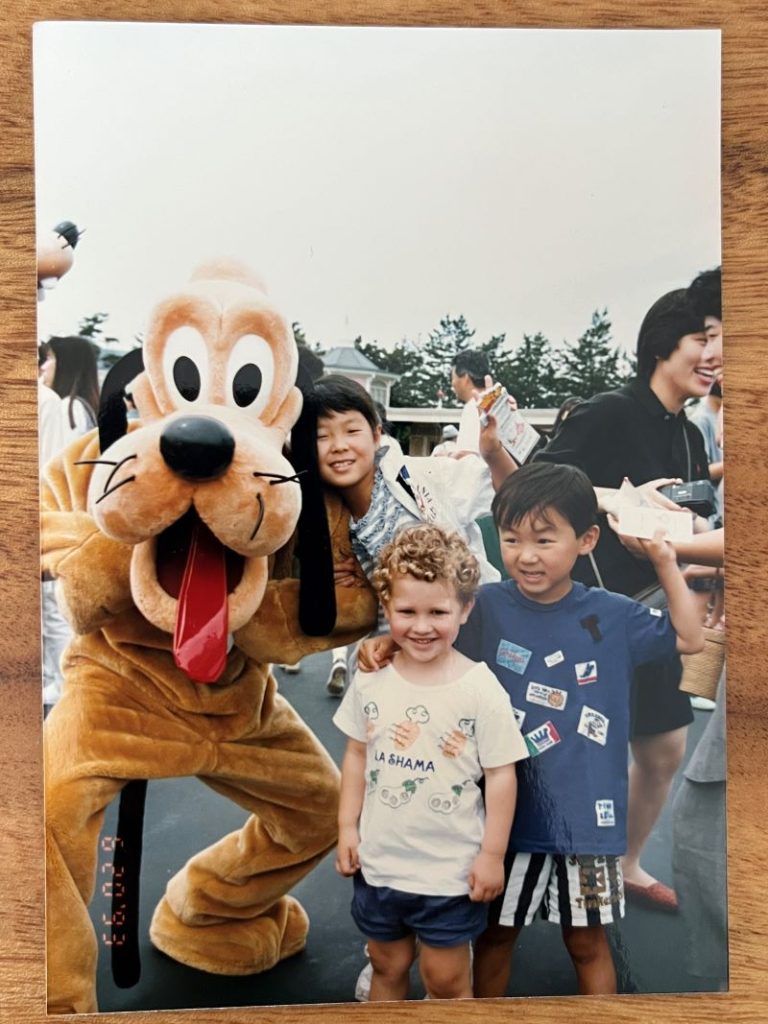

The author with his American and Japanese family. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

The author with his American and Japanese family. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

Citizenship

The topic was Japanese citizenship and whether I would consider applying for the opportunity to play pickleball in the Olympics. The problem is, Japan does not permit dual citizenship, so acquiring Japanese nationality means relinquishing American citizenship. At the time, I was the top pickleball player in Japan, and if pickleball were to become an Olympic sport, I would have been on the national team.

Would I give up United States citizenship for the chance to compete in the Olympics?

The pickleball team. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

The pickleball team. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

My reply was that Olympians are rarer than American citizens, so obviously yes. I’m married to a Japanese woman, and I feel more Japanese than American, so besides the hassle of paperwork, what’s the big deal?

But my mom’s visceral reaction made me realize the complexity of the issue. “How could you consider giving up on America? You would be abandoning your country. What if you ever needed to come home? And even with citizenship, you will never be treated as Japanese.”

Identity and Nationality

Today, the only reason I would choose Japanese citizenship is if I wanted to run for political office. That’s a long shot, so it’s probably never going to happen. But the interaction highlighted the complexity of Japanese nationality, ethnicity, and cultural identity.

The author as a schoolchild in Japan (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

The author as a schoolchild in Japan (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

If I were to gain Japanese nationality, would I have the words to describe myself? I would be legally Japanese, but appearances would still dictate a lifetime of explaining a long-winded origin story. I am not blaming the system or anyone in particular. It’s just the reality of the situation in a country where ethnicity is linked to identity and nationality.

After contemplating the issue, I see a dearth of vocabulary in both Japanese and English to describe someone who falls outside the normal categories. In America, the land of immigrants (someone please remind our current administration), we take it for granted that Americans can come from distinct ethnic, racial, cultural, or religious backgrounds. We have terms like African American, Mexican American, or Japanese American to describe types of Americans. Why the term Native American is common while the term White or Caucasian American is almost non-existent reveals something about our biases and who we consider “real” Americans. But that is a separate issue.

American Japanese, friends and family. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

American Japanese, friends and family. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

The problem with the term ‘Japanese’ (Nihonjin) is that it combines nationality, ethnicity, and cultural identity without providing a means to distinguish which one you are talking about. And it is increasingly common to find people like myself who feel culturally Japanese without looking the part. There is a gap in the ability to describe types of Japanese people because they never existed, or, like the indigenous Ainu, had never been acknowledged.

Describing Us

Describing Us

I propose adding terminology to help long-term residents of Japan and their children succinctly describe their situation. In English, for myself, it would be the exact opposite of Japanese American. I am an American Japanese.

With Japanese friends growing up. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

With Japanese friends growing up. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

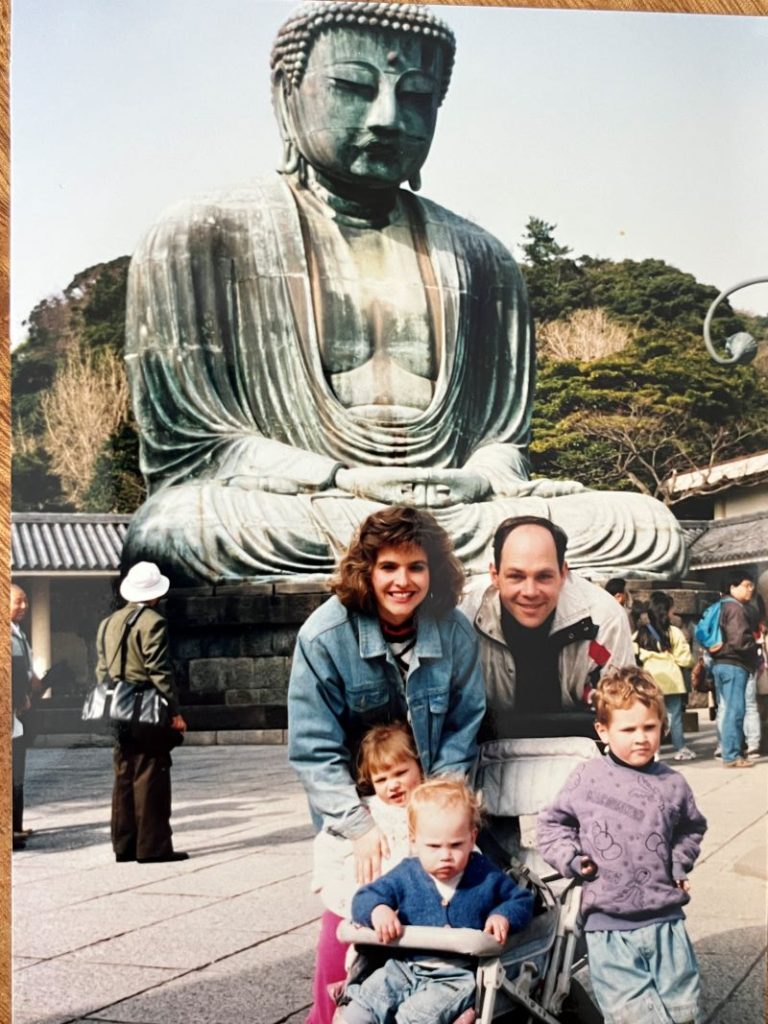

With his family, growing up in Japan. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

With his family, growing up in Japan. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

A person from any nationality can become both legally and culturally Japanese, combining the two identities. Before I was married, I actually used the term in my online dating profile to see what potential matches thought. They were confused, but at least they asked about it, getting me in the door. In Japanese, the term would be “Amerika-kei Nihonjin” or “American-type Japanese.” Who knows if it will catch on, but I think it’s an apt description for myself.

To explain my own identity, I use the analogy of a conversation. In America, when I enter a conversation with someone I don’t know, due to my appearance and American accent, they often start out thinking that we are quite similar. The longer the conversation goes, the more they realize that my background makes me quite different from theirs. In Japan, it’s the opposite. Because of how I look, people often think I am dissimilar from them at the beginning of a conversation, only to realize by the end that we are, in fact, quite similar.

I’m not saying you should only talk to people who are similar, only that you cannot judge a book by its cover.

With his Japanese son. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

With his Japanese son. (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

Bequeathing Immigrants with Japanese Values

The recent rise in nationalism and anti-foreign sentiment in Japan makes me realize the pertinence of this issue. Like in the US, the conversation is headed in a black-and-white, us-versus-them direction. However, just as the issue of ethnicity, identity, and nationality is nuanced and complicated, immigration is also a complex subject.

I actually sympathize with the Japan-first movement, because if Japan is not serving the needs of Japanese people, who is the country serving? However, Japan cannot isolate itself either and increasingly depends on immigrants and tourists to survive.

With visitors, there is definitely room for improvement in managing mass tourism and overcrowding. With immigration, some problems are inevitable, but immigrants make Japan significantly better by expanding its diversity. Broadening the definition of the word “Japanese” by welcoming more people into the country is the only way for Japan to remain economically and culturally relevant and to avoid population collapse.

In doing so, Japan will lose its ethnically homogeneous status. In my opinion, homogeneity was already a myth, but that’s another subject. Nevertheless, second-generation immigrants who have gone through the education system here will identify with every other aspect of what it means to be Japanese.

Ultimately, if Japan bequeaths to immigrants traditional Japanese values, such as its language, culture, traditions, and morals, it will continue the customs that helped it thrive. The people who continue those traditions may not look conventionally “Japanese.” But does that matter? Is it not more important for the traditions to continue, regardless of who carries them on? Japan must adapt to maintain its culture, but it has done so before and can do so again.

This is my life, I’m an American Japanese (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

This is my life, I’m an American Japanese (©Daniel Moore, Active Travel)

RELATED:

RELATED:

Author: Daniel Moore

Learn more about the wild side of Japan through Daniel’s essays.

Continue Reading

AloJapan.com