This is the final part of a six-part series looking at figures who have played a pivotal role in a modern football success story. The first piece, on the rebuilding of Ajax, can be found here. Part two, on Belgium becoming No 1 in the FIFA rankings, is here. Part three, on the rise of Croatian football, is here. Part four on the sport’s data pioneers is here. And part five on the creation of the England DNA is here.

You can listen to the related podcasts here on The Athletic FC Tactics Podcast feed.

Tom Byer takes a breath, one of less than a dozen which it feels like he takes over the course of 90 minutes, and from his Tokyo living room outlines his unique theory of development.

“When you can close the gap between the very best and the least developed, that’s where the magic happens,” he explains. “That’s what you see today in Japan. Our players are some of the most recruited players in the world right now. But the thing is, most people can’t explain why Japan have become so good. And that’s because they don’t understand grassroots football.

“People look at it more as an obligation than an opportunity. The common belief is that the battle for developing top players is primarily at the elite level. It’s not. It’s the entry level. The entry level is where the biggest disparity in football development is.”

Byer wants to reshape your thinking. The 64-year-old has lived in Japan for 40 years, from the ground floor of the country’s footballing evolution.

Over the decades, he has physically led more than 2,000 events, in every one of Japan’s 47 prefectures, helping transform a non-factor into one of the most technically adept nations in the world. His fingerprints lie all over its football — the J1 League, the 2002 World Cup, the development of Takumi Minamino, and Japan’s women becoming world champions.

Put together with his work in China, India, and the Philippines, where he has worked alongside stakeholders, literally millions of children have experienced the American’s methods. In terms of reach, he is arguably the most influential coach in the world.

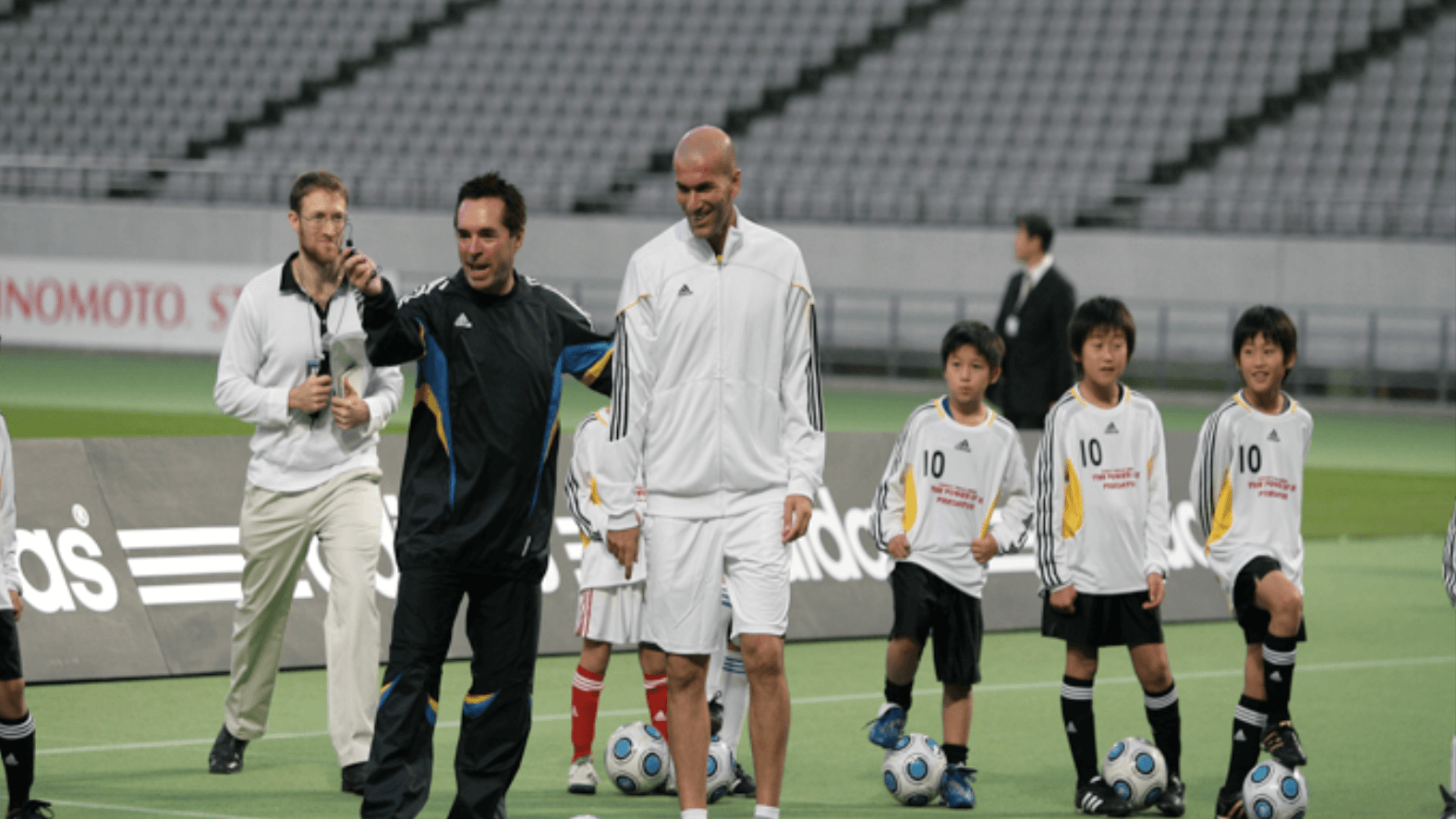

Tom Byer coaching alongside Zinedine Zidane at an Adidas event (Credit: Tom Byer)

It has been quite the journey for a man who admits that his professional career was, in his own words, average. Born in New York City in 1960, he played at college before moving to Japan in 1985, joining Hitachi Ibaraki SC and turning out for their second team. On retiring, he did not know what he wanted to do next — except for one thing. He had fallen in love with Japan and wanted to stay.

Japan, at the same time, was falling in love with football. The J-League (now J1 League) was founded in 1992, while, one year later, Japan applied to co-host the 2002 World Cup alongside South Korea. Japanese sport is largely funded by private companies — Byer started pitching to these brands, Nestle first, asking for support in running training camps.

Around that time, he also came across the work of Dutch coach Wiel Coerver, an influential if fringe figure in European coaching circles. Coerver believed skill level was not inherent but could be taught — one of his high-profile students was former Chelsea and Liverpool winger Bolo Zenden, who won 54 caps for the Netherlands between 1997 and 2004.

“When I stopped playing, I didn’t really have a methodology or philosophy other than the traditional perspective — shooting, passing and mini-games,” he explains.

“It wasn’t until I saw Wiel Coerver’s work that this changed. He had some resistance, but back in the 1970s, everybody believed you were born with skill and it couldn’t really be nurtured. But what Koerver did was shine a light on improving the level of individuals. What I wanted was to create a movement here in Japan.”

The question Byer asked himself was straightforward in conception. When FIFA has 211 member countries, why have only eight nations ever won a World Cup? Why have only five more than that ever reached a final?

“So the most common answer is that it comes down to coaching,” he says. “But if these coaches move around, any country can buy them, why aren’t more of them competing at the highest level?

“It’s not that. What those eight countries have is a culture of development that starts way earlier than everybody else does; it starts as early as a child starts to walk. The kids in the non-football countries are joining clubs to learn the basics — that’s the difference. You have to understand that. But the football world has not caught up to what science knows already, because skill acquisition happens much earlier than anyone expects.”

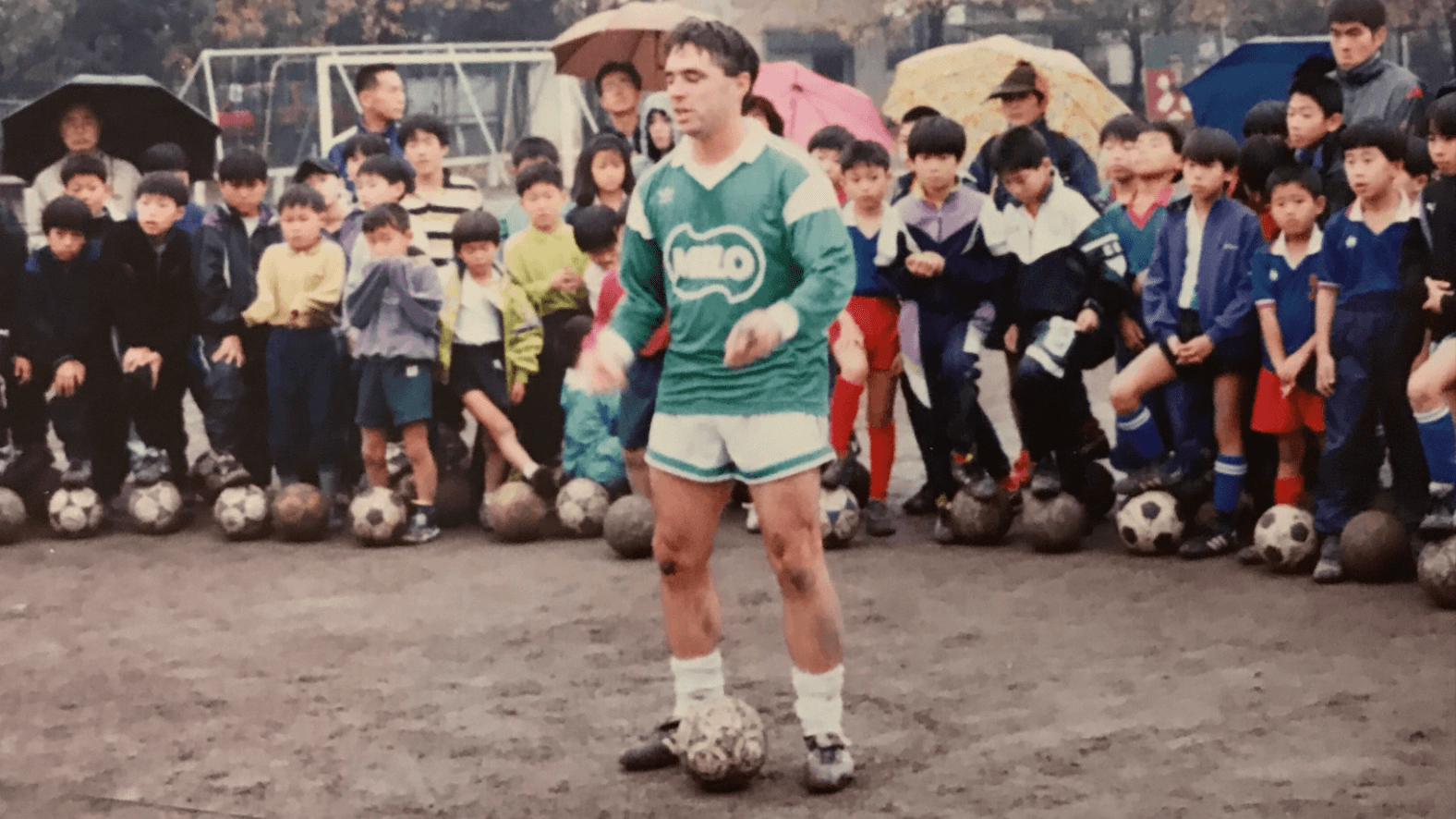

Byer in the late 1980s, as he launched his coaching career (Credit: Tom Byer)

Go to any park around the world on a sunny afternoon. There is a decent chance that you will find a parent and child playing with a ball. But in Byer’s mind, their method of play should diverge from your typical sight.

“You’re going to find kicking, shooting, dribbling with someone trying to chase them,” he says, waving his hand. “But what I want to talk about is ball mastery. It’s much bigger than football. It’s a mental and physical exercise — the mind and body working as one, to allow the brain to create a chemical signature of the experience. That’s an emotional connection. It’s how deep learning and long-term memory takes place.”

Byer uses his own two children as examples throughout. When they were young, he placed balls all round the house, discouraging them from kicking and instead promoting ball mastery — close control, keeping the ball tightly on a leash. Both his children, now in their late teens, are pursuing professional careers.

“There’s a common thread with all the top players in the world — Messi, Ronaldo, Suarez, Iniesta, Kane. They don’t fall in love with football. They fall in love with the ball first. Takumi Minamino, as a toddler between one and three, he started practising with his dad inside and outside the house. Same thing with our other boy, Takefusa Kubo. He started when he was two or three with his dad.”

Byer claims that 95 per cent of a child’s brain is developed by the age of five or six. He calls this type of play “installing software” — uploading implicit memory into the unconscious mind via the cerebellum. It means that, by the age of six, children already have an innate technical ability.

“Obviously, all kids can improve,” he says. “But there does seem to be a window or gate that closes when it comes to skill acquisition at a very young age.

“And so if you want to have a paradigm shift in football development, develop an army of little five and six-year-old boys and girls that are skilled at ball mastery before they cross the line into organised play. The old European mantra of just let them play ball games, it works, but only if you have kids that have mastered the basic fundamentals. Then they can benefit from more complex movements.”

Byer at an early training class (Credit: Tom Byer)

Japan has its own benefits for skill acquisition. There is no off-season for the majority of activities — while culturally, children specialise early rather than becoming multi-sport athletes, flying counter to the perceived western wisdom. Instead, a six-year-old will be expected to train four times a week, with training sessions lasting up to three hours.

The self-evident question is one of fun. Externally, if children are discouraged from shooting, asked to specialise at an early age, and face long training sessions, is the entertainment of childhood being given up in favour of technical ability? Not according to Byer, who sees the early stages of ball mastery as crucial for bonding with parents. He calls his method Football Starts At Home.

“A little two-year-old is not going to go dancing around in an empty room with nobody watching,” he argues. “So they’re constantly developing this parent-child bond that is almost impossible to replicate with a coach at these younger ages.

“None of this falls in the context of teams, coaching, competition, winning, losing. It falls in the context of families. And this is a bias that manifests in a very positive way. When these kids turn up to organised practice on their first day, they’re going to be the most popular kids on their team. When the coach says ‘Four to a ball’, they’re going to go to the good kids’ ground. They become the leaders as well. It’s not a wonder that most captains at youth ages are the best players.”

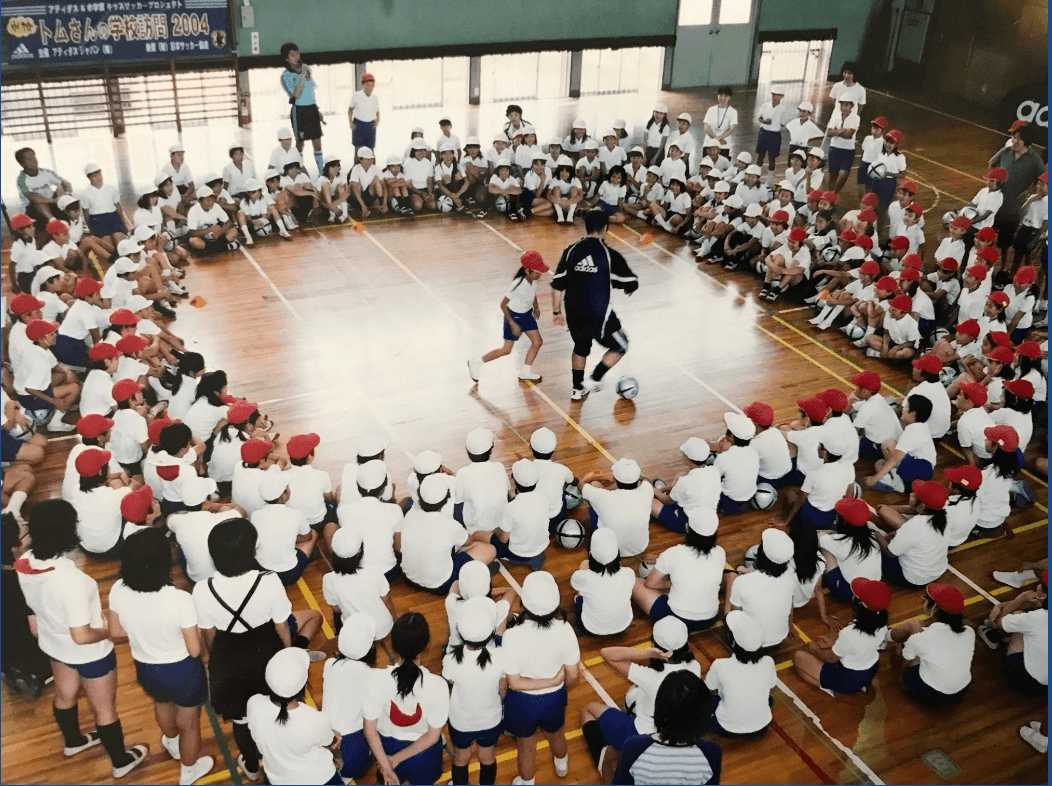

Over the years, Byer was somewhat prophetic in using a multimedia approach to spread his work. Scarcely a delivery model existed in Japan that he did not touch. He had a regular corner in the majority of the major football magazines, outlining drills. He was the Nintendo Game Boy default character in the 2000s. Adidas tapped him to run campaigns. He appeared on VCRs, DVDs, and manga comics.

The most significant by far, however, was television. He appeared on Oha Suta, Japan’s most popular breakfast children’s show, presenting the “Tomsan’s Soccer Technics” feature daily. Born out of Pokemon, he joined the programme a few months before the World Cup, where he was beamed to five million viewers for 13 years. All in all, he produced 3,500 training clips. It made him one of the most recognisable figures in Japanese football.

The Japanese Football Association was taking notice. Byer travelled across Japan alongside a former international named Asako Takakura, running over 80 grassroots events each year as well as helping operate the JFA’s eight regional training centres as the technical specialist. He coached a national Under-12 selection; Takakura coached the girls. Eventually, Takakura rose to Under-17 head coach (where she won the 2014 World Cup), to the Under-20s, to coaching the national team, which she helmed from 2016 to 2021.

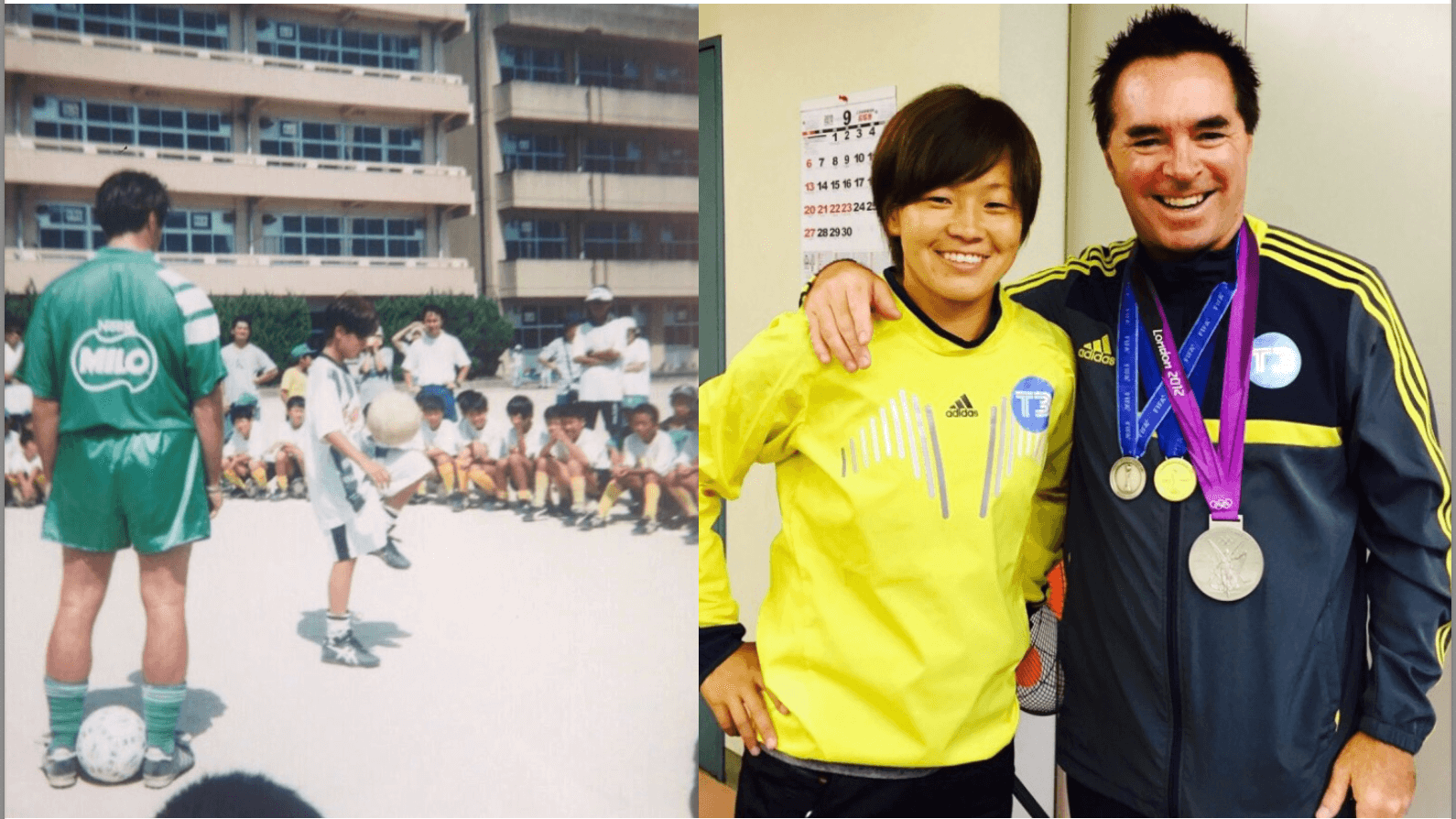

One of the regulars at Byer’s camp was Aya Miyama — who, in 2011, led Japan to World Cup victory.

“She came to those events,” says Byer. “We took her overseas to play. I’ve known her since she was a little girl. I wanted to popularise the women’s game here because people don’t realise we only have 30,000 girls that are registered to play football here in Japan. That’s a tiny number.

“But yet, we’ve won all three FIFA World Cup competitions — Under-17, Under-20 and the senior World Cup — and we did that in the space of seven years.”

Byer with a young Aya Miyama (left) and wearing her World Cup winners’ medal (Credit: Tom Byer)

It is notable that Byer uses ‘we’ for Japan throughout. He describes their 2011 World Cup win as his proudest moment in football, several members of the squad having graduated from his camps.

“That was the year that Japan had the earthquake, the tsunami, and the nuclear meltdown,” he remembers. “In the last game, I was asked to come into the TV broadcaster, but I couldn’t do it. I wanted to be by myself. I knew I would be emotional about it, I even get it right now. My whole career has been here; I played here, coached here, built a house here, made a business. I have people in every single team, whether it is the players, the coaches, or the administrators.

“And I remember that game because Aya, the girl from our schools, scored the equaliser to send it into extra time. I was an emotional wreck.”

He is confident that Japan’s men are the next side due to break through, their team similarly made up of his proteges, who grew up watching him on . They were the first side to qualify for the 2026 World Cup in the United States.

“In the last World Cup window, five of the players came from our school — Takumi Minamino, Ritsu Doan, Ayase Ueda, Wataru Endo, the captain, and Reo Hatate over at Celtic,” Byer lists. “Reo came from the Under-12 selection I coached.

“It’s unusual to have five kids, and they’re only the ones I know of. They’re the big numbers — No 8, No 9, No 10, No 11 — they all come from our schools.”

Minamino and Byer are still close. Back at the 2022 Qatar World Cup, Japan won plaudits for their bravery on the ball and technical brilliance. They deservedly beat Spain 2-1, the reigning European champions, as well as defeating Germany. Though they have not reached the latter stages of the World Cup like their female counterparts, they have only exited the last two tournaments by the barest margins, to a miraculous Belgian comeback and on penalties to extra-time specialists Croatia.

Minamino and Byer are still close (Photo: Kenta Harada/Getty Images)

“Nobody thought we’d make it out of the groups because of Spain and Germany, two World Cup giants,” says Byer. “It’s not at all impossible for us to get to a semi-final or final. But will they? The difficulty is that we need better competition in Asia, we ran through everybody to qualify. We need a stronger China, a stronger Thailand, a stronger Vietnam. We need India and Indonesia. I think that’s what might push Japan over the edge — stronger consistent opposition. There’s no doubt in my mind that this team now is the best we’ve ever had.”

Though he has been invited to the likes of Ajax, Manchester United, and FIFA’s headquarters, Byer is at his most excited when speaking about his work across Asian football. Last December, the AFC invited him to Seoul to present his ideas to all 47 member countries. In China, meanwhile, he presented a TV show alongside David Beckham which ran every day for a year, both working as Adidas ambassadors.

“In Asia, we have 630million children under the age of six,” he says, his speech accelerating. “India has 180million. China has another 120million. And there’s no development strategy for these kids, because they haven’t crossed the line into organised play yet. To me, that’s the missing piece of the puzzle.

“But because there’s less of a football culture, that’s why it’s easier to get the buy-in. We work with schools and put these strategies in place, working with parents to explain why their kids are coming home with a little ball. And they can see the degree of focus and attention.”

These are all long-term plans — it takes at least 15 years for three-year-olds to develop into players capable of contributing at international level. In Japan, the first players to have come through Byers’ programmes are now approaching the twilight of their careers. Having hit a height of ninth in the world rankings, who could follow Japan into the world’s top 10?

Currently, Byer is working closely with the Philippines FA, shaping the football strategy of a nation with 17million children under six.

“They’re the first country of 211 to actually adopt Football Starts at Home as their first official pathway,” he exclaims. “I was there five times last year, going on a 33-state tour. This is going to be the next story in 10 or 20 years. People are going to say: ‘What the heck happened in the Philippines?’ And again, nobody’s going to understand it.”

AloJapan.com