As rising sea temperatures are affecting marine life in the waters around Japan, konbu (kelp) harvests in Hokkaidō have fallen by two-thirds in the past 30 years.

Unprecedented Water Temperatures

Rausu, a town on the Shiretoko Peninsula in eastern Hokkaidō, is known for the production of high-grade konbu (kelp), a key ingredient in Japanese cooking. However, producers have been growing anxious in recent years. Seawater temperatures have been abnormally high, and they are seeing more cases of poor growth.

Dried Rausu konbu, used to make dashi soup stock is popular for its strong umami taste. (© Yamamoto Tomoyuki)

In autumn 2023, the ocean surface temperature off the coast of Rausu reached 25º Celsius. Local fishers were astonished at this unprecedented temperature.

Konbu is a seaweed that grows in cold waters. If the water temperature is too high, it grows poorly, due to issues like weakened roots causing the plant to break free.

Konbu harvesters in Rausu, Hokkaidō, in July 2024. (© Yamamoto Tomoyuki)

Rausu konbu falls into two categories: natural, which grows from the sea floor, and cultivated, which is grown attached to ropes suspended in the ocean. In 2023, it was the cultivated konbu which was most heavily impacted. A number of producers suffered a 50 to 80% decrease in harvest.

Two-Third Decline in 30 Years

Natural konbu accounted for 69.5% of konbu harvested in Japan in 2023, and the remainder was cultivated.

Hokkaidō produces some 95% of Japan’s overall konbu harvest. On the Pacific Ocean coast, konbu grows as far south as the waters of northern Ibaraki Prefecture, and northern Aomori Prefecture on the Japan Sea coast, but still the majority grows off the Hokkaidō coast.

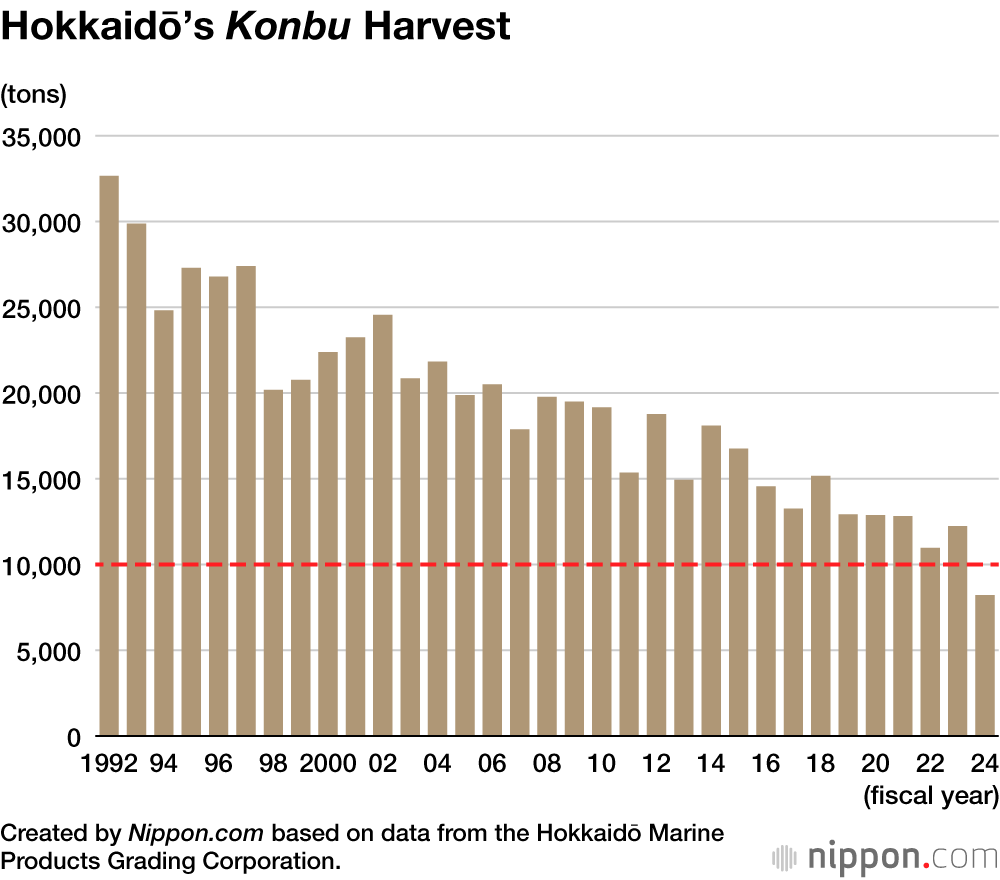

Essentially, whether Japan enjoys a good or poor konbu harvest depends on the conditions in Hokkaidō, where harvests have fallen by two-thirds over the last 30 years. The ongoing decline in harvests is not limited to Rausu, but is taking place across Hokkaidō.

According to data released in April 2025 by the Hokkaidō Marine Products Grading Corporation, 8,213 tons of konbu was harvested in the prefecture in fiscal 2024. The amount has fallen below the 10,000 ton mark, as illustrated in the above graph. The impact of recent increases in ocean temperature due to global warming is seen as a major cause of the decreasing harvest.

Effects on Kelp Varieties

What will become of kelp as global warming continues to advance? A research team at Hokkaidō University conducted computer simulation of the effects of increases in ocean temperature on 11 different types of kelp (order Laminariales).

The results indicate that, even based on the “intermediate scenario” (RCP4.5) of the four climate change scenarios described by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its Fifth Assessment Report (an increase in surface air temperature of 1.1º to 2.6º by the end of this century), it is highly likely that four varieties of kelp (Saccharina longissima, Arthrothamnus bifidus, Saccharina gyrata, and Saccharina coriacea) will disappear completely from Japanese seas. In the worst-case scenario, RCP8.5, which assumes continued high levels of greenhouse gas emissions and a surface air temperature increase of 2.6º to 4.8º, ocean temperatures will rise even further, which could result in the loss of six kelp varieties from Japan’s coastal waters.

Saccharina longissima konbu drying in the sun. Photo taken in Nemuro, Hokkaidō, in June 2023. (© Yamamoto Tomoyuki)

Drift Ice Also Decreasing

Each winter, drift ice (ice floes) from the Sea of Okhotsk reach Hokkaidō’s northern coastline. Drift ice is frozen seawater that is unattached to the coast and instead floats in the ocean. Cold winds from the continent cause large volumes of sea ice to form off the Sea of Okhotsk coasts of Siberia and the island of Sakhalin. This becomes ice floes as it is driven south by wind and ocean currents toward Hokkaidō.

Ice floes in the Sea of Okhotsk. Photo taken in February 2025. (© Yamamoto Tomoyuki)

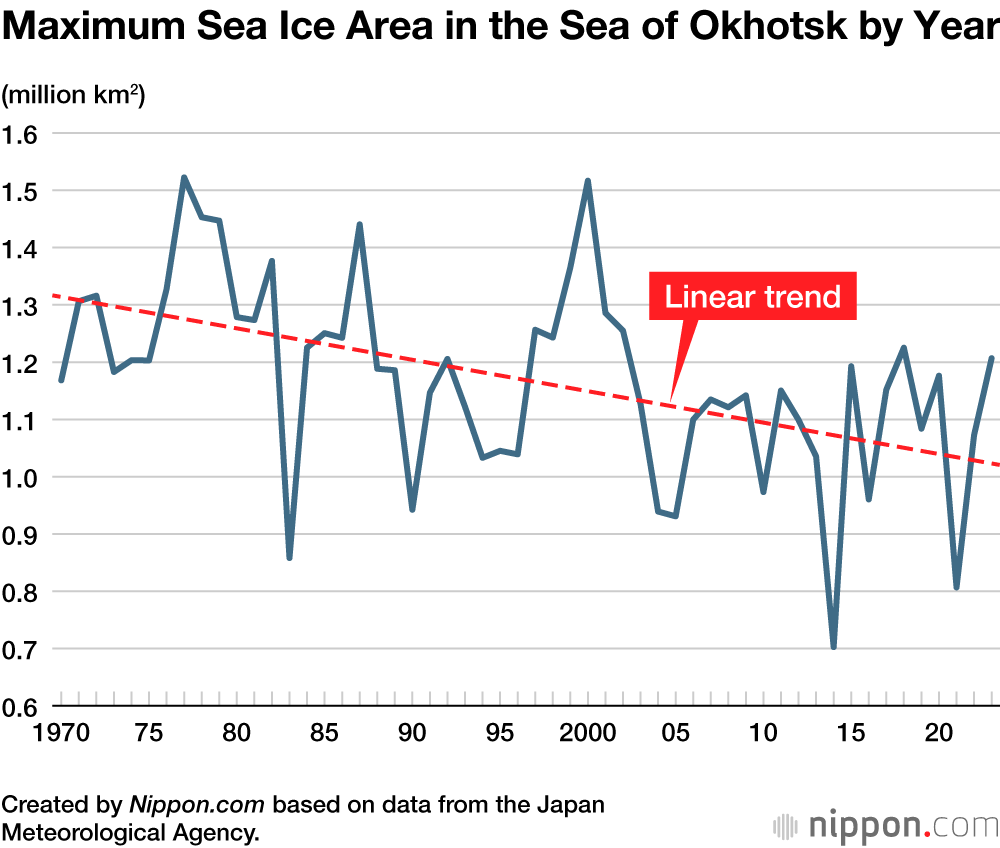

But the impact of rising ocean temperatures is also starting to be seen here. According to the Japan Meteorological Agency, the amount of sea ice in the Sea of Okhotsk is decreasing. The maximum area of sea ice is falling by 56,000 square kilometers every 10 years, equating to an overall 3.5% decrease each decade.

Research aided by a supercomputer forecast that if global warming continues, the area of ice floe in the Sea of Okhotsk south of the 46th parallel, close to Hokkaidō, will fall to one-third of the average area from 1994–2017 by 2050, even based on the IPCC’s lowest level scenario of greenhouse gas emissions.

Based on the mid-range greenhouse gas emission scenario, the area of ice floe will decrease to one-quarter by 2050, and the high-end scenario would see it fall to one-fifth. Some forecasts suggest that in the future there may even be years when no drift ice appears off Hokkaidō’s coast.

Impact on Scallops

Hokkaidō’s drift ice draws tourists from Japan and around the world. But it is more than just a tourism resource.

It also contains abundant iron originating in the Amur River. In spring, when the ice melts, this iron is released into the ocean. This in turn leads to a proliferation of phytoplankton, which plays a vital supporting role in the ocean’s entire ecosystem. For example, phytoplankton is an important food source for Hokkaidō’s famous scallops.

If the drift ice that reaches the Hokkaidō coast declines as forecast, it will negatively impact other marine products, including scallops.

There are concerns about a negative effect on scallops from the decline in drift ice. Photo taken on the ocean floor of the Sea of Okhotsk off Hokkaidō on October 2023. (© Yamamoto Tomoyuki)

Ocean warming does more than merely change the areas of distribution of marine life; it influences the overall ecosystem and impacts marine products in a more complex manner.

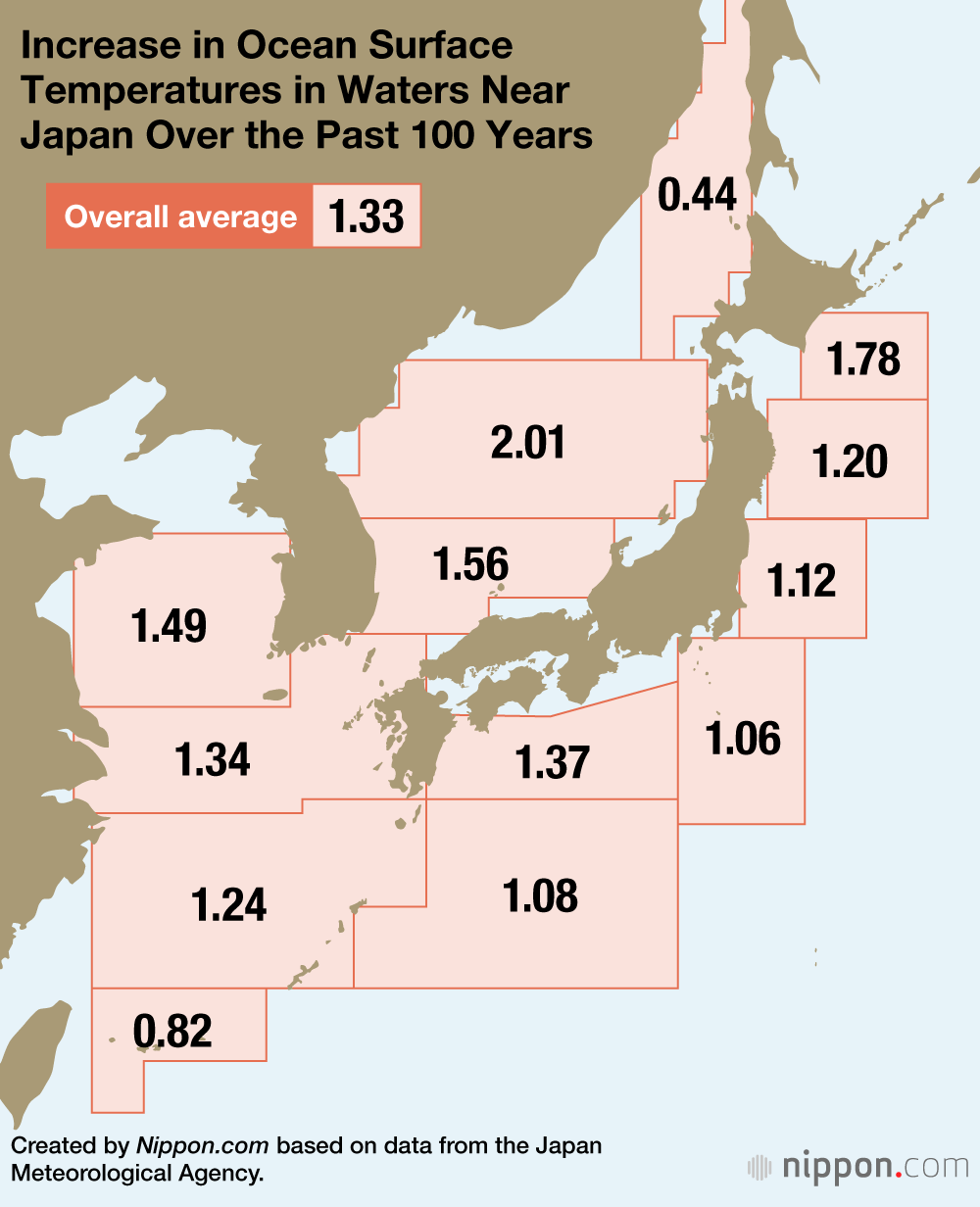

Ocean Warming Near Japan Twice the Global Average

Ocean temperatures near Japan have increased 1.33º over the past century, a level twice the world average. As overall land temperatures are rising more than those for the sea, it is believed that this affects Japanese waters near to the continent. There is also an impact on the Kuroshio Current, the north-flowing ocean current on the west of the Pacific Ocean.

The rise in ocean temperatures caused by global warming is also resulting in more frequent marine heatwaves, when statistically rare high temperatures are recorded for five consecutive days or longer.

There is a huge impact on marine life from a rise of even one degree in average water temperature, and changes in the distribution of life-forms are being reported around Japan.

Hauls of scabbard fish, a large fish prized on Japanese tables, are declining in western Japan, while they have increased 25-fold over the past decade in the northern prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima. Similar patterns have been reported across Japan.

Spiny lobster has been sighted in waters as far north as Iwate Prefecture. Photo taken off the Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture in July 2024. (© Yamamoto Tomoyuki)

Changes in Marine Life Likely Due to Global Warming

Konbu (kelp): Harvest reduced to one-third in the past 30 years in Hokkaidō, its main production area.

Salmon: Hauls have fallen in Hokkaidō and the Sanriku region, but are favorable in Russia and Alaska.

Pacific saury: Warmer coastal waters off Japan are one cause for a declining catch.

Buri (yellowtail): Previously plentiful in Nagasaki, Shimane, and Fukui, but recently in abundance further north in Tōhoku and Hokkaidō.

Fugu (blowfish): Large hauls in Fukushima and Hokkaidō, plus a rise in crossbreeds.

Nori: Higher ocean temperatures have shortened the cultivation season, and harvests have declined.

Coral: Bleaching is becoming conspicuous in Okinawa and other areas.

Spiny lobster: Their northern boundary has extended from waters off Ibaraki up to Sanriku.

Sawara mackerel: Increased hauls in northern Sea of Japan.

Scabbard fish: Decreasing numbers in western Japan, rapid rise in Tōhoku.

Monitoring Changes Below the Surface

Global warming is having an impact below the ocean surface, unseen by most people. Abnormal occurrences are more likely to pass unnoticed in the sea compared with those on land.

Although the changes taking place may be small initially, as they continue and compound, they are certain to have a noticeable impact on our dining tables in the future. Measures being undertaken to reduce global warming, such as energy-saving initiatives and the introduction and expansion of renewable energy, not only help to mitigate harm from heatwaves and torrential rains but are also essential for protecting the future of the seafood that is so dear to Japanese people.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 4, 2025. Banner photo: A cluster of kelp seen underwater off the coast of Rausu, Hokkaidō in May 2024. © Yamamoto Tomoyuki.)

AloJapan.com