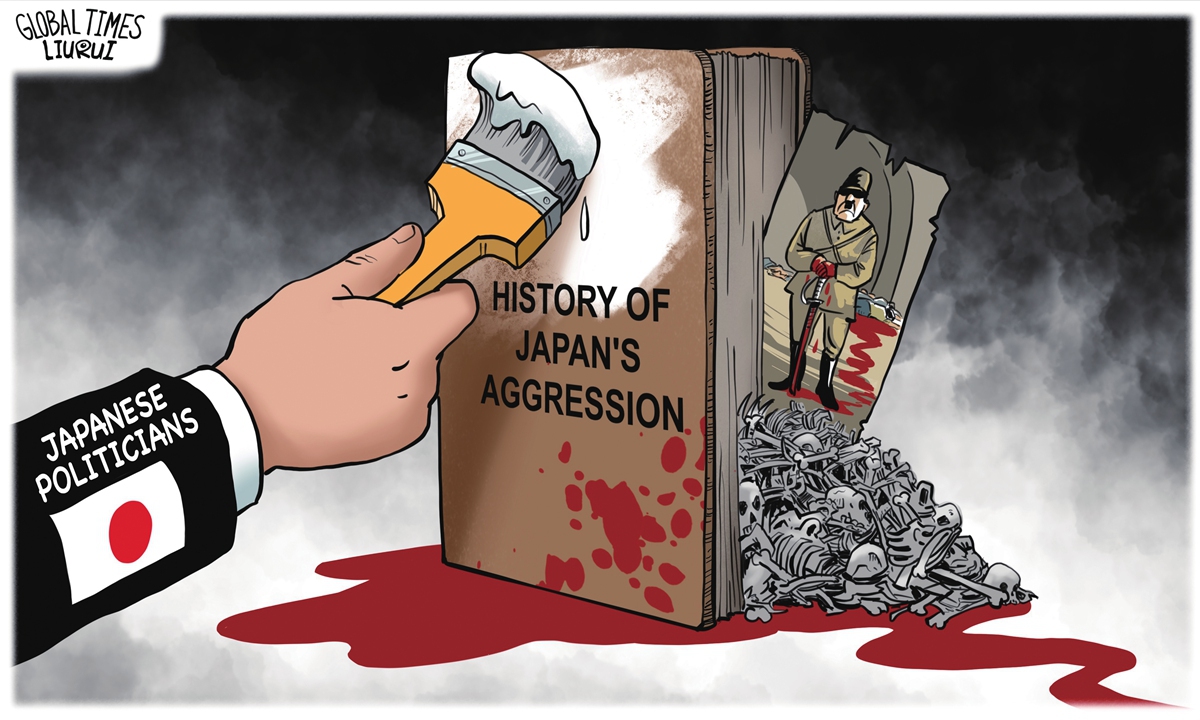

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

According to Japanese media reports, under pressure from conservative forces within the party, Japan’s Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is considering not announcing his view in a form of written statement on relevant historical recognition on August 15, the anniversary of Japan’s defeat, or on September 2, the day Japan formally signed the surrender document, and relevant coordination is underway. Since the 1995 “Murayama Statement,” it has become customary for successive Japanese governments to issue statements on historical issues during “decade” anniversaries. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the World Anti-Fascist War and Japan’s unconditional surrender. On the issue of historical recognition, the Japanese government should clearly express the appropriate stance to the international community. Any attempt to downplay the history of aggression or evade responsibility for reflection is a challenge to international justice and a detriment to Japan’s own international credibility.

In 1995, then Japanese Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama issued a statement titled “On the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the War’s End,” in which, for the first time as a sitting prime minister, he acknowledged Japan’s “colonial rule and aggression” and expressed “deep remorse” and “heartfelt apology.” In 2005, Junichiro Koizumi’s statement largely followed the spirit of the “Murayama Statement.” In 2015, Shinzo Abe’s 70th-anniversary statement, although attempting to end the “apology diplomacy,” also continued the postwar tradition of the Prime Minister expressing his historical views. These documents form the cornerstone of rebuilding trust between Japan and its Asian neighbors, serving as a litmus test for the international community to gauge whether Japan has truly returned to the path of peace. If this tradition is interrupted this year, it will not only anger some Japanese citizens and deeply disappoint Japan’s Asian neighbors but also raise doubts and concerns in the international community about the country’s future direction.

Japan’s reintegration into the international community and the restoration of normal relations with neighboring countries after World War II were built on reflecting on its history of aggression and pledging never to wage war again. This is not only an apology and repentance to the victimized countries but also Japan’s self-redemption. When political considerations outweigh historical responsibility and evading reflection becomes the “safe option,” it reflects an atmosphere in Japanese society lacking the necessary introspection about that war. In recent years, with Japan’s rightward political shift, historical narratives have increasingly been shaped by right-wing forces, who have long downplayed or denied wartime atrocities. A dangerous “victimhood narrative” has also taken hold in Japan, emphasizing the suffering from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Tokyo firebombing, while avoiding discussion of the root causes of these tragedies – it was Japan’s aggressive expansion and harm that provoked the just counterattack by the Allied forces against fascism. The Yasukuni Shrine still enshrines Class-A war criminals, and some Japanese textbooks continue to be evasive about the Nanjing Massacre, inevitably causing Japan’s younger generation to drift further from historical truth.

In tandem with this regression in historical recognition, Japan has been taking increasingly bold steps in recent years to “loosen” its security constraints. It has accelerated efforts to revise its pacifist constitution, amended the “Three Principles on Arms Exports,” forcefully passed new security laws, lifted the ban on collective self-defense, sharply increased defense spending, acquired so-called “counterstrike capabilities,” developed and deployed offensive weapons, and continuously broke through the “exclusively defense-oriented” framework. Some right-wing Japanese scholars even irresponsibly claimed that Japan’s moves to expand its military and prepare for war are “too weak and too slow.” These developments have triggered serious concerns among Japan’s own citizens, its neighboring countries and the international community, constituting a serious provocation to the victory of the World Anti-Fascist War and the post-war international order.

The stability of historical understanding is a crucial part of the cornerstone of a nation’s credibility. After World War II, Germany was able to earn the forgiveness of its European neighbors precisely because it consistently and thoroughly reflected for decades on the crimes committed under Nazism. In contrast, Japan’s reflection on its history of aggression has remained evasive, using vague terms like “the end of the war” or “the fifteen-year war” to downplay the nature of the war. This only further undermines trust with Asian countries that once suffered under Japanese aggression. In this context, the absence of a prime ministerial statement would send an unsettling signal: Is Japan prepared to abandon its long-held postwar commitment to being a “peaceful nation” grounded in historical reflection?

Facing and treating history with the right attitude is a crucial prerequisite for Japan’s return to the international community in the postwar era. Properly addressing historical issues is a political foundation for stable China-Japan relations. Over the past 80 years, there have been times – represented by the “Murayama Statement” – when many peace-loving Japanese politicians and civic groups set positive examples by actively correcting societal views of history. At this historical juncture of the 80th anniversary of the end of the war, Japan should not continue to evade responsibility under the highjack of right-wing forces, but instead courageously face its history.

AloJapan.com