Syllabus: Environment

Source: IE

Context: In a landmark advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has clarified that the Kyoto Protocol (1997) remains legally valid and binding, even after the Paris Agreement (2015) came into effect.

About ICJ Ruling Revives Legal Status of Kyoto Protocol:

What is the Kyoto Protocol?

Adopted in 1997, entered into force in 2005 under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

It was the first binding international treaty mandating emission reductions by developed nations (Annex-I countries).

Based on the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR–RC).

Had two commitment periods: 2008–2012 and 2012–2020.

Key Obligations:

Emission reductions by Annex-I countries (from 1990 baseline).

Finance and technology transfer to developing nations.

Creation of mechanisms like Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

Why Was the Kyoto Protocol Considered Obsolete?

The Paris Agreement (2015), with a universal and bottom-up structure, replaced Kyoto’s top-down, binding targets with voluntary NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions).

The US never ratified the Kyoto Protocol; Canada, Japan and others exited or stopped complying.

No third commitment period was adopted post-2020.

Post-Paris, the protocol was considered defunct in operational and legal terms, though never formally repealed.

Significance of the ICJ Ruling:

Legal Continuity Reaffirmed: The ICJ ruled that lack of new commitment periods does not mean termination. Kyoto remains part of international climate law.

States Can Be Held Legally Accountable: Non-compliance with Kyoto targets may now constitute an “internationally wrongful act”, reviving the possibility of state responsibility under international law.

Retroactive Assessment Permitted: Even past obligations (e.g., first commitment period targets) are open for review and compliance assessment.

Scope for Climate Litigation Expanded: Though the opinion is non-binding, it empowers civil society and states to pursue stronger climate litigation and demand accountability.

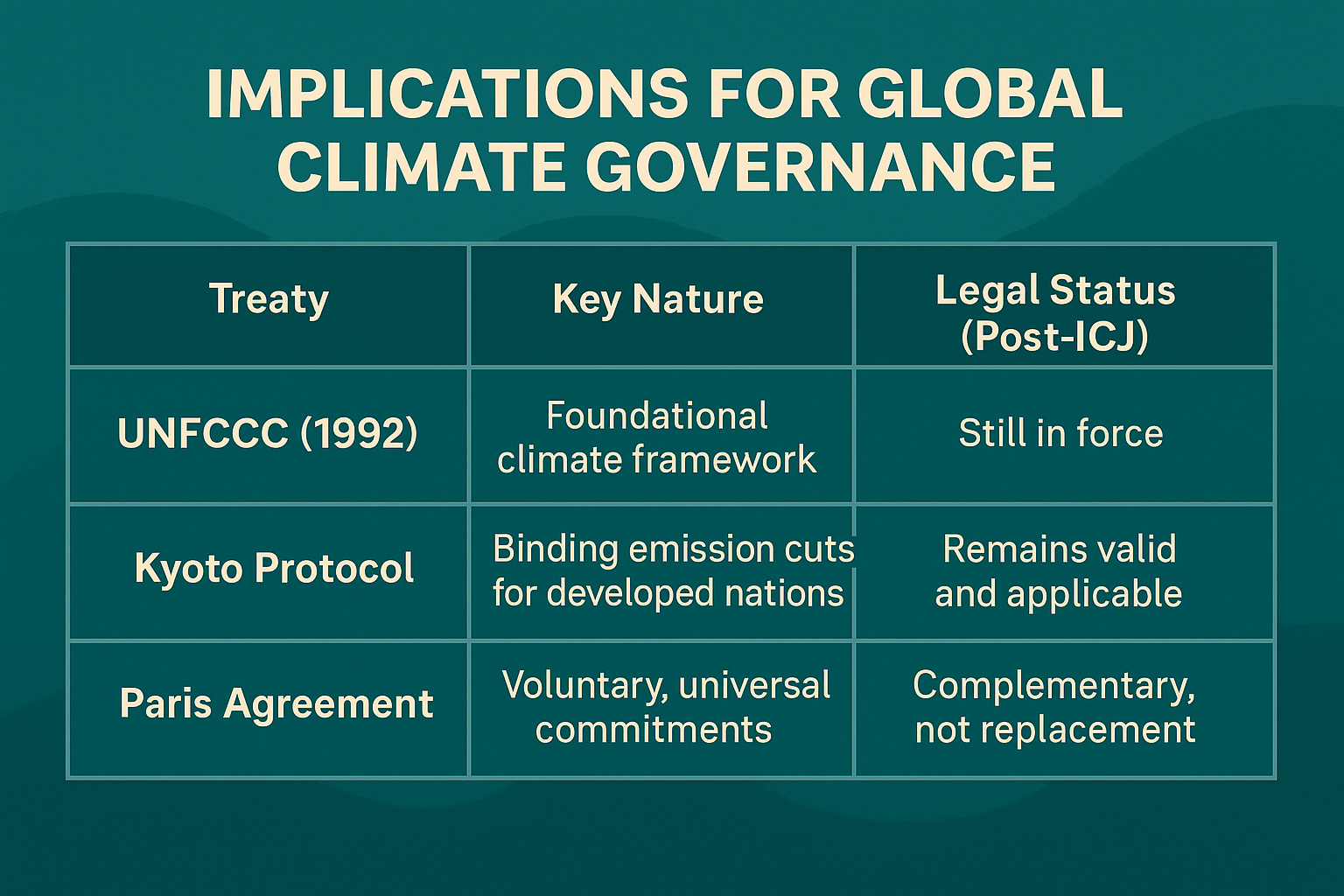

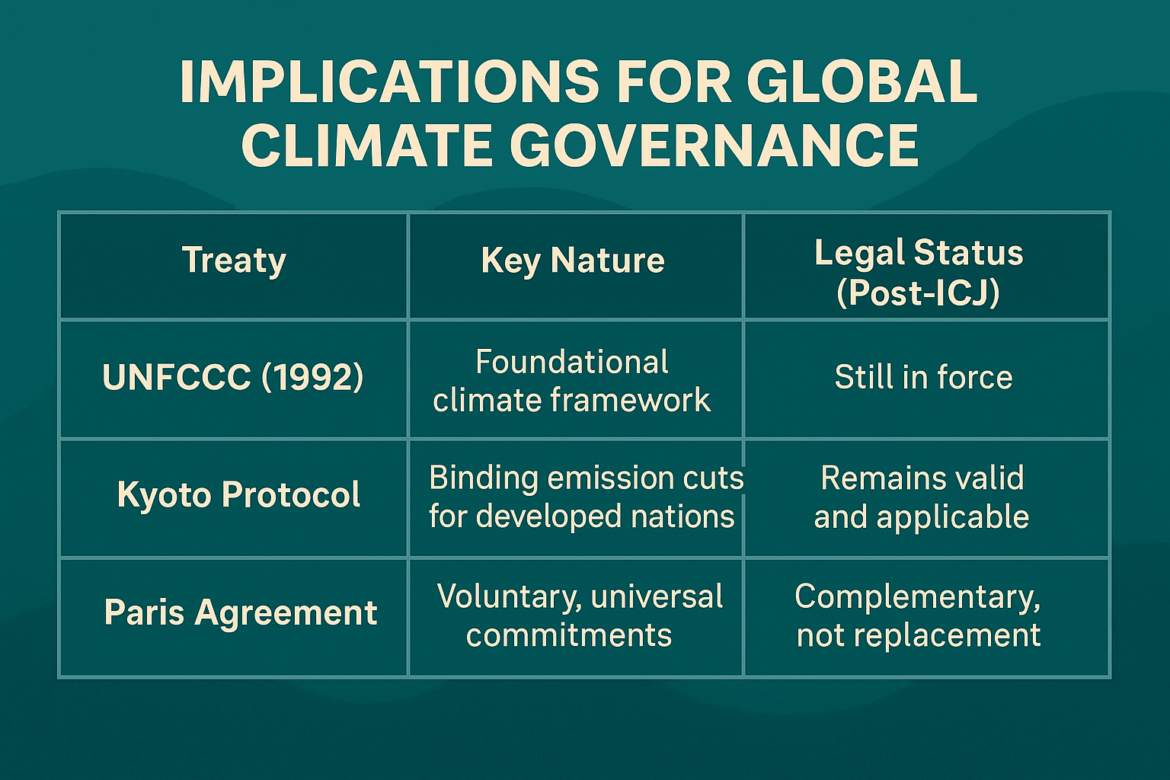

Implications for Global Climate Governance:

The ruling underscores treaty coexistence, not substitution.

It revives CBDR–RC principle, often diluted under Paris structure.

Developed nations may face renewed legal scrutiny for historical emissions.

Challenges in Implementation

US non-ratification: The US never ratified Kyoto, weakening global adherence and setting a precedent for other developed nations.

No enforcement mechanism: Kyoto lacked penalties for non-compliance, making targets non-binding in practice.

Paris vs Kyoto conflict: Paris allows voluntary pledges, undermining Kyoto’s binding legal obligations and accountability.

Geopolitical rivalry: Tensions like US–China mistrust hinder consensus on global climate obligations and reforms.

Way Forward:

Reactivate Kyoto monitoring: Track and assess past commitments to reinforce legal climate accountability.

Strengthen Paris transparency: Apply Kyoto-style reporting rigor to improve trust and target comparability.

Expand climate jurisprudence: Use ICJ rulings and tribunals to build legal clarity on state climate obligations.

Revive North–South equity: Ensure finance, tech transfers, and burden-sharing aligned with CBDR principles.

Merge legal and voluntary models: Create a hybrid system combining Kyoto’s obligations with Paris flexibility for effective governance.

Conclusion:

The ICJ’s ruling has resurrected the Kyoto Protocol’s legal relevance, transforming it from a forgotten relic to an active instrument of climate accountability. It signals that historical emissions, past obligations, and the principle of equity cannot be brushed aside in the climate fight. While not binding, this ruling adds moral and legal pressure on developed nations to deliver on their long-pending climate promises.

AloJapan.com