Five years ago, the acclaimed architect Hiroshi Naito was met with an unusual request: He was asked to design a five-story structure in the middle of Tokyo with no specific purpose. The RINRI Institute of Ethics, a private social education organization, gave him free reign, proposing that the building’s function will be decided according to its design. Thus, Kioi Seido, also known as “the building with no purpose,” was brought to life.

Well, not entirely free reign. According to a statement by Naito that was distributed at the exhibition, “My client’s only order was that I think about the Jomon [period]” — a prehistoric era of Japanese history that stretched from around 13,000 to 400 BCE, known for its mysterious clay figurines, knotted-rope pottery and an aesthetic that feels both ancient and strangely abstract.

“I think what they wanted was something that was not bound by capitalism or current common sense, but something that would stir emotions,” he continues. The resulting structure is understated, yet otherworldly — a synthesis of warm and cool tones, earthy and industrial textures, which combine to create an atmosphere at once familiar and disorienting.

Today, Kioi Seido stands by a small intersection in the heart of Chiyoda City. A quietly extraordinary sanctuary, it may escape your notice at first glance. It’s not typically open to public viewing, but for a limited time only — until September 30, to be exact — a special exhibition will allow visitors to enter the building for the first time in two years.

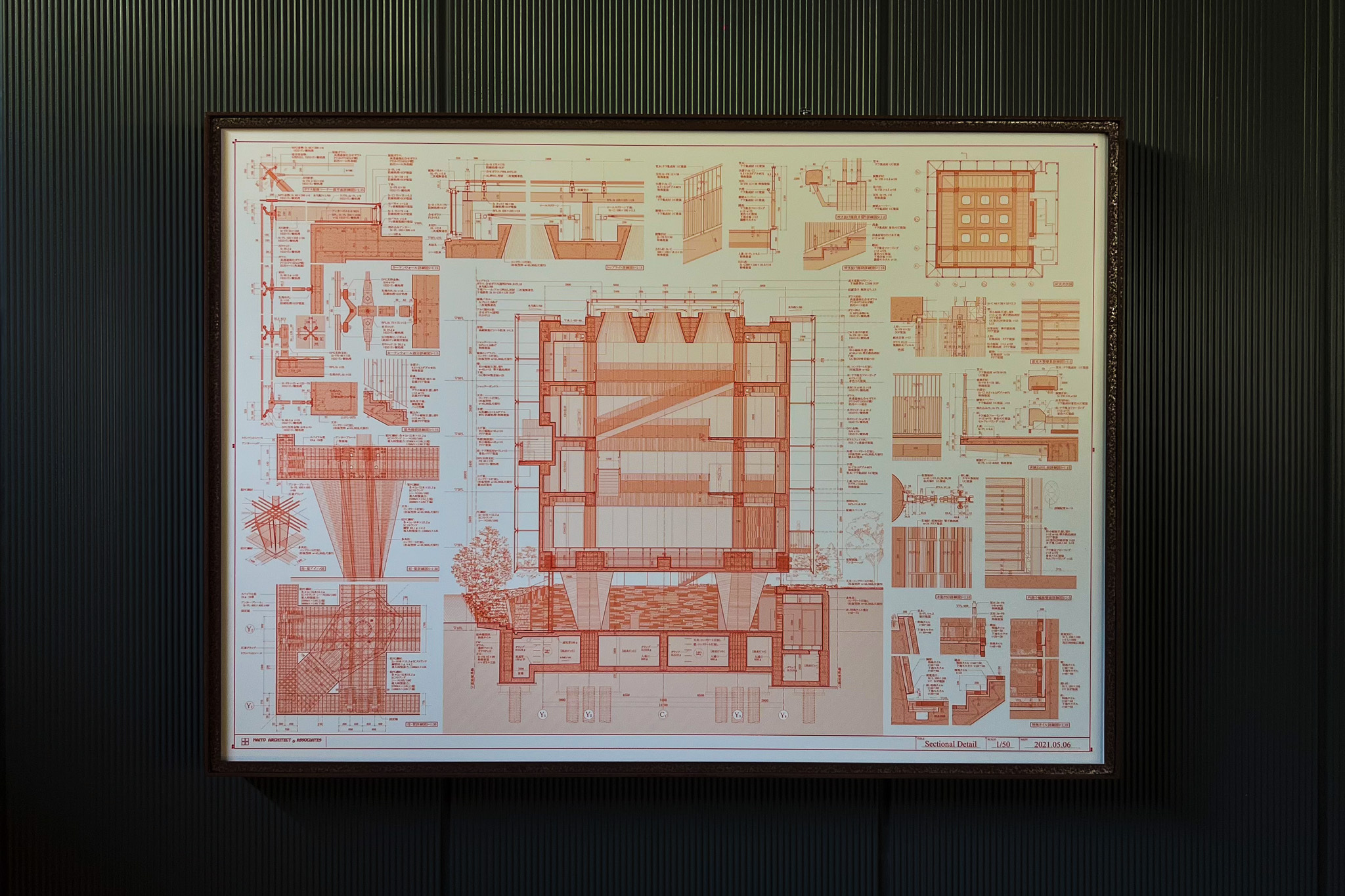

It’s not just a rare chance to see the hypnotic beauty of its interior firsthand; the exhibition also showcases 40 years’ worth of diaries and sketches by Naito himself.

A Crack in the Extraordinary

“When you find yourself in this mysterious space, with the first floor deeply reminiscent of the ancient Jomon period and the second floor and above extending into the future, you will forget the routine of everyday life and feel a ‘crack in the extraordinary,” says Toshiaki Maruyama, Chairman of the RINRI Institute of Ethics.

Although it’s not immediately obvious from the outside, Kioi Seido’s concrete cube form is supported by four polygonal pillars. They cocoon an installation on the ground floor, which features 18,800 glass pieces laid in a ring formation, each representing someone lost or missing in the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. The charcoal-colored tiles that coat the space all vary in sheen and shape, many of them repurposed from tiles originally used in Shimane Prefecture’s Kametani kiln.

Requiem for the Great East Japan Earthquake

From the second floor upward, warm cedar planks, exposed concrete and beams form a four-story atrium, shrouded in light and shadow. Nine craters on the ceiling form sky lights that feel at once futuristic and timeless, each tapering upward in a slight curve. As you climb up each story and walk around, every angle offers a new perspective.

The Modern Pantheon

Ascending Kioi Seido’s staircases is a peaceful, comforting experience, but also strangely hypnotic — it feels as though you’re suspended in time and space, divorced from the external world.

Naito was drawn to the Pantheon in Rome, the only Roman building to remain practically intact for centuries. He endeavored to create something immortal and innately magnetic. “Neither the purpose nor the function of [the Pantheon] is well understood,” reads Naito’s statement. “If the question was to be purposeless, I wanted to build a modern Pantheon.”

In conceptualizing Kioi Seido, Naito engaged with questions of tradition and modernity posed by architect Seiichi Shirai. In his hugely influential essay “The Jomon Style” (1956), Shirai uses the raw, unmediated aesthetic sensibility of Jomon period objects as a vehicle to argue that architects must look beyond easily recognizable stylistic elements, and focus on the “inner potential” — the underlying spirit — of forms.

“I believe [Shirai’s inquiry] was an alarm bell to a society that was striving for rapid modernization,” Naito remarks. “Seventy years have passed since then, and I took the question posed this time as the same one.”

Naito is likely referencing what’s known as the “Jomon–Yayoi dichotomy,” a concept that gained traction among Japanese architects in the postwar period. Sparked by a broader national conversation about identity and tradition, the debate centered on whether Japanese architecture should draw inspiration from the raw, expressive forms of the Jomon period or the more refined, orderly aesthetics of the Yayoi era. Using raw concrete, a material used since ancient times, and glass, a highly precise and refined industrial product, Naito symbolically melds the elements of tradition and modernity into a harmonious whole.

While the building’s complexity and beauty alone is reason enough to visit, the exhibition of Naito’s meticulous notes, sketches and diaries offers a fascinating glimpse into his mind. From the second floor up, you can browse 40 years worth of his plans, inspirations and thoughts. On the floor of the atrium is an installation named the “Mandala of Words,” showcasing fragments from Naito’s writings.

About Hiroshi Naito

Born in 1950 in Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Hiroshi Naito is one of Japan’s most acclaimed and visionary architects. Upon earning a bachelor’s and master’s degree in architecture from Waseda University, he worked under architect Fernando Higueras in Madrid and under architect Kiyonori Kikutake in Tokyo. Naito established his own firm, Naito Architect & Associates in 1981, and was a professor at the University of Tokyo from 2001 to 2011, when he became professor emeritus.

His major architectural works include the Toba Sea-Folk Museum (1992), the Shimane Arts Center (2005) and the Kusunagi Sports Complex Gymnasium (2015). Naito’s creations emphasize the harmony between the built environment and its natural surroundings, with a focus on technical durability and sustainability. Often balancing wooden and concrete textures, his gently minimalistic works evoke warmth and humility.

More Information

Exhibition Title:

“Architect Hiroshi Naito – Anything and Everything: Diaries and Sketches of Thoughts in Kioi Seido”

Dates & Hours:

July 1 – September 30, 2025

Open Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays (excluding holidays and closure dates: Aug 12, 14, 16 & Sep 23), from 10 a.m. – 4 p.m. (last entry 3:30 p.m.)

Admission:

Free, no reservation required

Address:

Kioi Seido, Ethics Research Institute

3-1 Kioicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

(10 min from JR Yotsuya / 5–6 min from nearby subway stations)

Notes:

– No parking or luggage storage

– No high heels allowed inside

– Restrooms located on the first floor

– Photography is allowed, without tripods

– Please refrain from taking photos of the notebook exhibits, talking loudly, eating or drinking

Related Posts

AloJapan.com