(Damian Flanagan)

Article and photos by Damian Flanagan

The City of Bilbao, the capital of the Basque Country in the north of Spain, is a place that was famously rejuvenated and reinvigorated through art. Suffering industrial decline and depression, its grand Victorian buildings and riverside warehouses fell into neglect and dilapidation, and about 30 years ago I doubt that few people outside Spain had even heard of Spain’s fifth largest urban area.

But then like the goddess Athena suddenly descending onto the stage, one of Europe’s most famously distinctive modern art galleries, the Guggenheim, was built in Bilbao and the city’s fortunes were transformed. Bilbao became a tourist Mecca, a must-see, and with the infusion of tourist dollars came a rediscovery of all the other great things Bilbao has got to offer — its bustling medieval quarter and its grand central boulevard (that is quite the match of anywhere in Paris) and its delightful parks and Opera House and riverside walks.

(Damian Flanagan)

Bilbao is a lot to take in and a lot of fun. My younger daughter and I hired bikes and breezed about the lanes of the city in the hot days of early summer, reserving energy for the hard yards of the Guggenheim and other galleries. We obediently weaved our way between labyrinthine concrete walls, and exhaustive displays of abstract expressionism, a loan exhibition of five centuries of art from Budapest, and caverns of multi-media installations. And then we got to the Museum of Fine Arts of Bilbao and had centuries of local Basque artists to get through. By Day Three, I was thinking, “If I have to look at another painting…”

We were back cycling past an intriguing building, the Azkuna Zentroa, an old wine market in the centre of the city that had lain derelict for three decades and been renovated into a kind of interior forum with shops, auditorium, library, fitness centre and exhibition space. There was a show on by a Japanese artist I had never heard of called Chiharu Shiota and so, with almost heavy heart, I felt professionally obliged to descend into the bowels of the building and give some more art a go. I’m glad I did so because it turned out to be the most outstandingly memorable exhibit of everything we saw in Bilbao.

(Damian Flanagan)

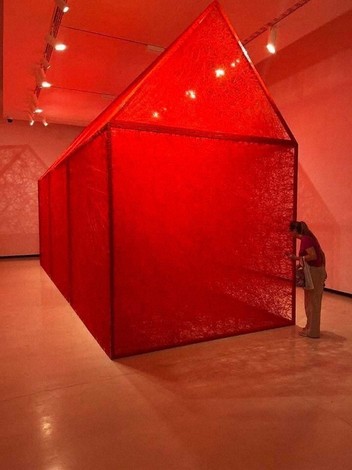

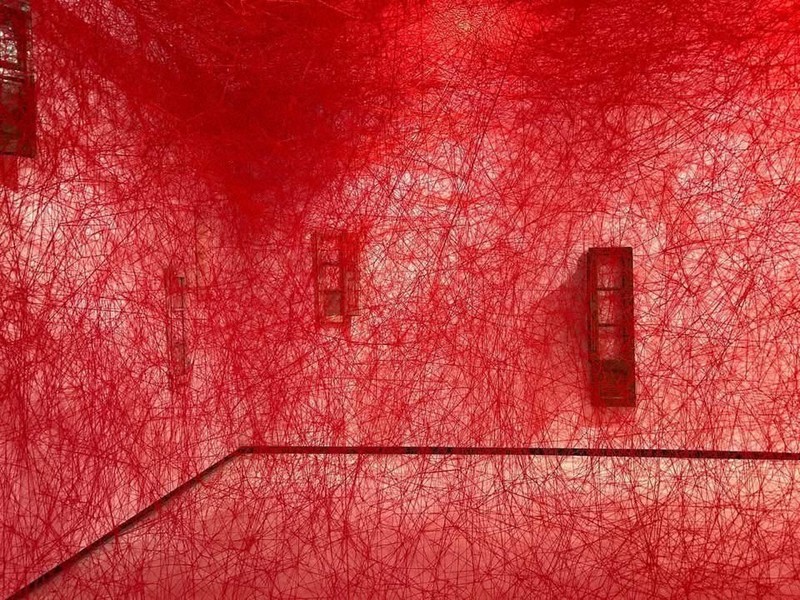

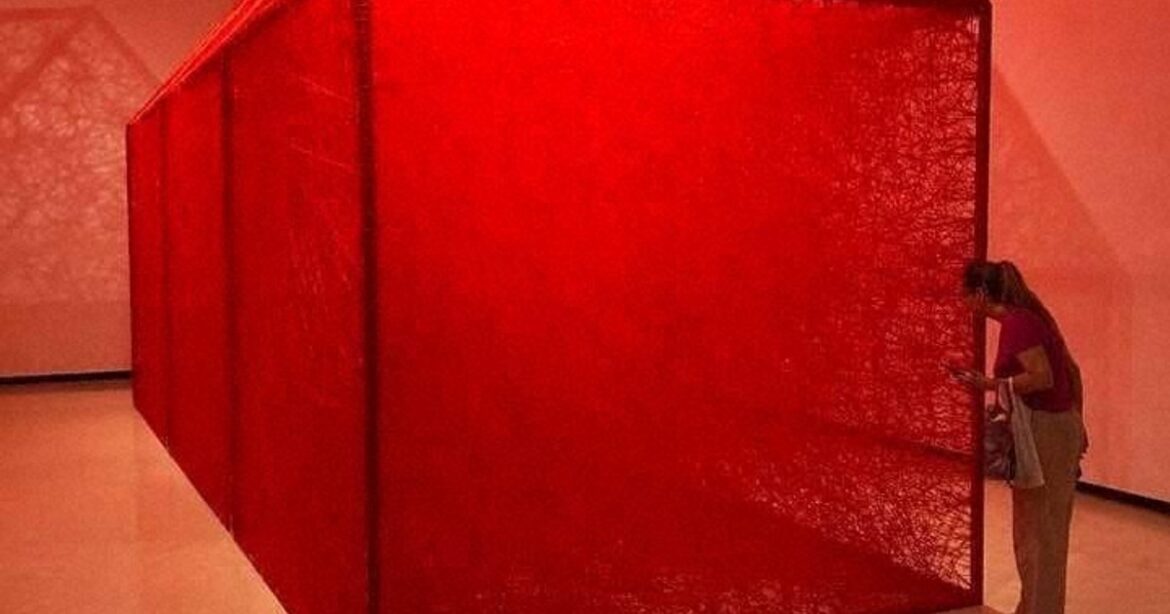

The expansive foyer of the building was punctuated by a crimson clue — completely unnoticed by me as we entered — to what was coming: billowing blood red lengths of cloth, like sails in the sky. Downstairs in the exhibit proper, you first enter a large room containing a house completely conjured from vibrant red thread. Another room leads you on a pathway around a community of dwelling-like spaces, all composed of red threads. The effect is a curious one. You feel a sense of calm and something soothing, while yet being aware that the red threads hint at capillaries of blood. Are the strands really meant to signify blood, that most unsettling of substances, or was that simply my imagination making an unwarranted connection? And why, then, is the effect so calming?

(Damian Flanagan)

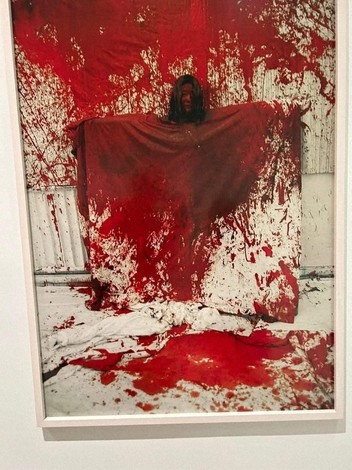

When you enter the third room, all starts to becomes clear. We move back in time to the beginning of Shiota’s career and a long-standing connection to the obsessive theme of “blood”. Trying to uncover a deeper reality in her artworks, Shiota hit upon the idea that she was showing a calm, socialized, pleasant face to the world while something far more disturbing and terrifying lurked inside her psyche. Her facade of creamy skin was hiding the explosive, painful potentiality of blood that was her true inner essence. Shiota’s inspiration was to expose the primeval and interior, so she first dressed the human body in a white surplice daubed with the messy confusion of blood, like a sacrificial victim, and then stripped naked, daubed in blood, and rolled in the muddy earth. This is art that is literally baring all, stripping away artifice and taking considerable risks.

This is not the gentle art some might stereotypically expect from a Japanese artist. But then I noted that Shiota, now a longstanding resident of Berlin, originally hails from Osaka. And as anyone familiar with that metropolis will know, the people of Osaka are a brand apart — grittier, more outspoken, funnier and far “earthier” than many of their Japanese compatriots.

(Damian Flanagan)

Having explored her theme of being defined by an interior narrative of “blood”, Shiota developed the subject in numerous intriguing ways. There is a picture of an hour glass composed of blood-like particles as if our entire lives are measured by each dripping pulse of blood, and a large hanging installation of what looks like the organs of menstruation. Proceed into the fourth and final room and we discover a hospital bed set up with a drip, hinting at the rites of both our bloody entrance and often our exits from the world, and finally an entire labyrinth of tubing to walk around, pulsating with a blood-like substance connected to a heart-like pump, the ultimate exteriorisation of the blood networks contained, mostly unconsciously, within our mortal frame. It’s an unnerving and sobering space to contemplate the mechanics of your own existence.

In a world obsessed with classifications of skin into White, Black and Brown, you are suddenly acutely aware that the true hidden colour of all human beings is, underneath it all, Red. I was reminded of the words of Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice”, “If you prick us, do we not bleed?”

(Damian Flanagan)

You wander back through all this visceral “blood-art” to the rooms in which you entered and contemplate again why that community of dwellings made up of blood-red threads appears as so strangely soothing. And then it came to me. Because blood as well as signifying pain and mortality is also the means by which we construct families, homes and communities.

(Damian Flanagan)

Blood ties are most frequently the means by which a home is kept together, through birth and death just as much as the physical materials hold together the buildings themselves. Having the company and support of people with whom we share familial blood is a foundation stone of society, and can ground and comfort us from the slings and arrows of a sometimes hostile exterior world, and a sometimes precarious solitary interior existence.

“Blood runs thicker than water” runs the adage, and you can reflect on that ancient wisdom as you perceive the means by which Shiota has skillfully sublimated an unnerving landscape of self-questioning “blood-art” into an affirmative outer protective womb of blood threads.

I read afterwards that Shiota often personally works on the construction of the installations, labouring through the night to get them finished on time, as if the very process of construction is an integral part of the artistic journey. I imagined her “sweating blood” to ensure her blood threads were knitted together on time. This blood-red contemplation of the true nature of existence is one assuredly worth taking.

(Damian Flanagan)

@DamianFlanagan

(This is Part 67 of a series)

In this column, Damian Flanagan, a researcher in Japanese literature, ponders about Japanese culture as he travels back and forth between Japan and Britain.

Profile:

Damian Flanagan is an author and critic born in Britain in 1969. He studied in Tokyo and Kyoto between 1989 and 1990 while a student at Cambridge University. He was engaged in research activities at Kobe University from 1993 through 1999. After taking the master’s and doctoral courses in Japanese literature, he earned a Ph.D. in 2000. He is now based in both Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture, and Manchester. He is the author of “Natsume Soseki: Superstar of World Literature” (Sekai Bungaku no superstar Natsume Soseki).

AloJapan.com