The Japanese economy, long a model of prosperity and fiscal discipline, is going through a period of complex turbulence. Between a contraction in its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a consumer crisis, trade tensions and structural weaknesses, the world’s fifth-largest economy seems to be caught in a spiral that is difficult to halt.

A slow but steady decline

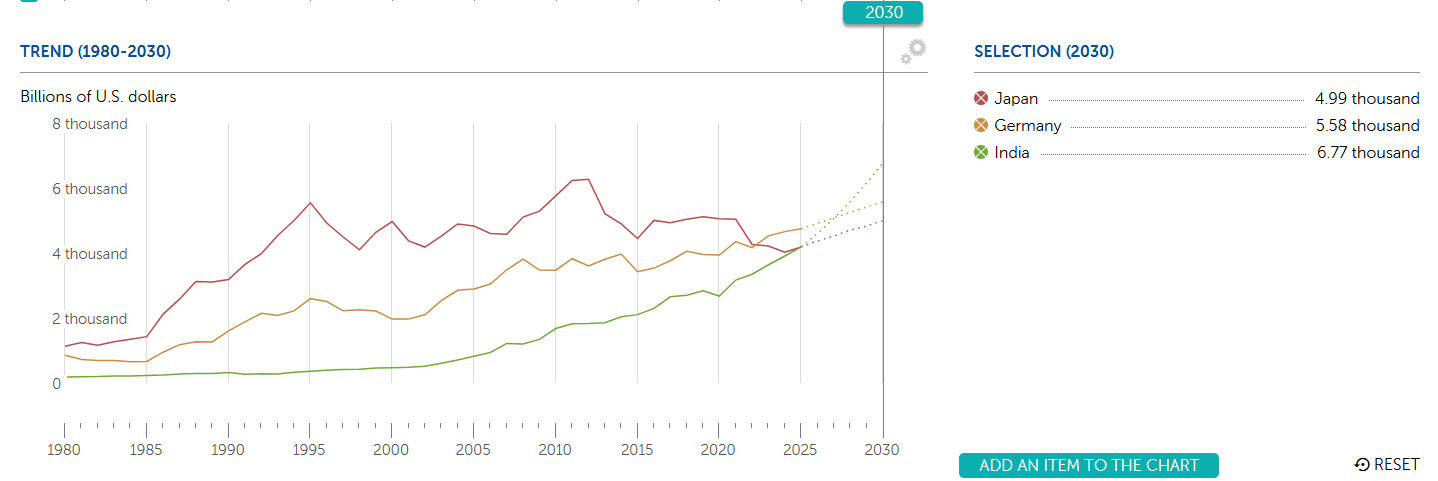

In 2024, Japan officially relinquished its position as the world’s third-largest economy to Germany, in terms of nominal GDP in dollars. This year, it could happen again with India. These are symbolic events, but they reveal a structural dynamic: Japan’s economy has been slowing sharply for 20 years, and has been steadily losing ground since 2012.

This loss of rank is due first and foremost to weak long-term growth, at 0.7% per annum between 2000 and 2022 according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), compared with 1.2% for Germany, for example. But declining demographics and the steady depreciation of the Japanese Yen (JPY), which reduces the value of GDP expressed in foreign currency, have also contributed to Japan’s downgrading in the world rankings.

The Japanese economy contracted by a further 0.2% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2025, continuing the underlying trend in a country with strong human capital but no clear growth engine, torn between exceptional monetary policies and growing budgetary constraints.

The recent international trade tensions initiated by US President Donald Trump only serve to accentuate an already extremely delicate local situation.

Indeed, the IMF’s latest projections now anticipate that Japan could also be overtaken by Indonesia in terms of GDP at purchasing power parity as early as the 2030s.

Source: IMF

Domestic consumption not picking up

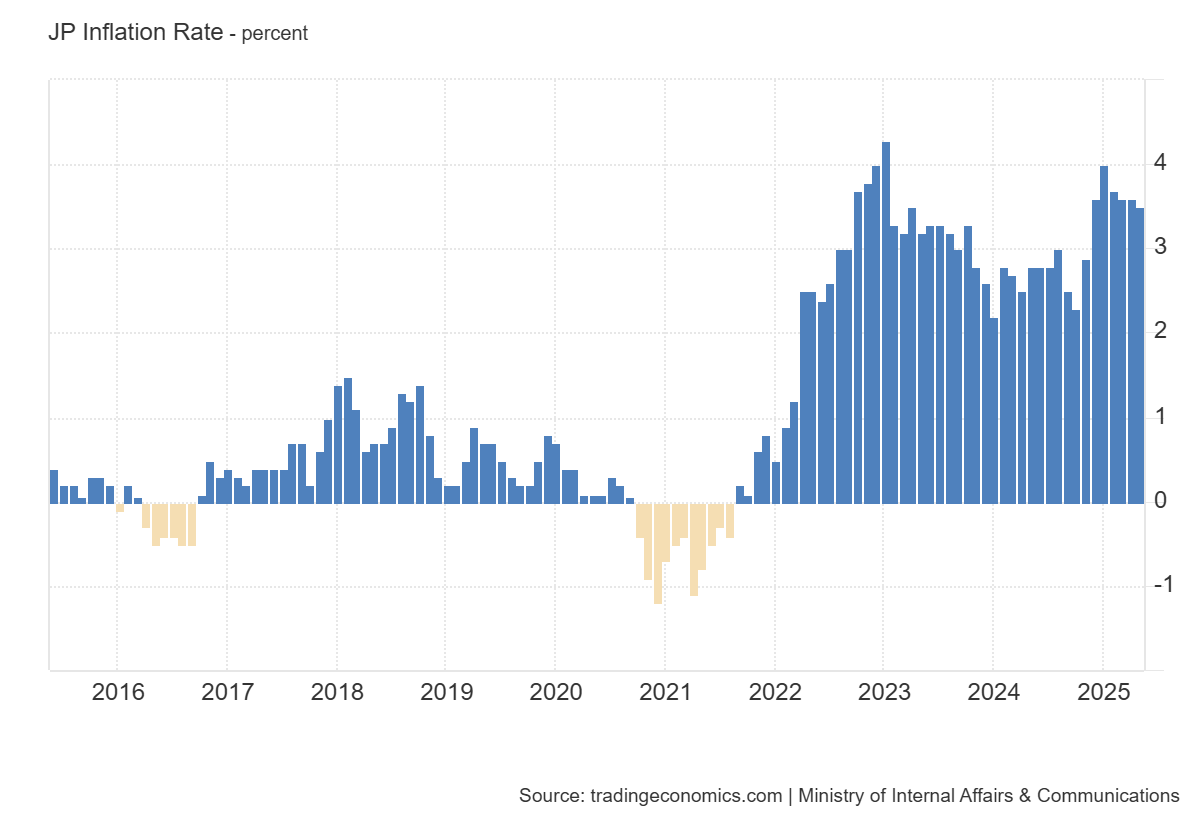

Household consumption, which accounts for more than half of GDP, remains a major challenge for the Japanese economy. Despite historic wage rises of 5.1% in 2024, the highest in 30 years according to Yourstory, inflation has eroded purchasing power.

Real wages are stagnating, and commodity prices, notably energy and food, are weighing on households. Inflation has soared since 2022, reaching 4% in January, slowing to 3.5% for May.

Consumption has thus remained below its pre-COVID 2019 level, reports CNN Business. And recently announced tax measures, such as the increase in the income tax exemption ceiling, are expected to have only a marginal impact of around 0.4% of GDP at best, economists say, again according to the CNN Business report.

Suffocating demographics

Japan’s population has shrunk by more than 4 million in a decade. By 2025, over 28% of the population is over 65, the fertility rate has fallen to 1.15 children per woman by 2024, and the working-age population has declined by over 10% since 1995, according to Yourstory.

This demographic dynamic is deteriorating the country’s productive base, increasing the burden of social spending, and dragging down potential growth.

In particular, Japan is facing a structural labor shortage, and despite the gradual opening up to skilled immigration, the pace remains insufficient.

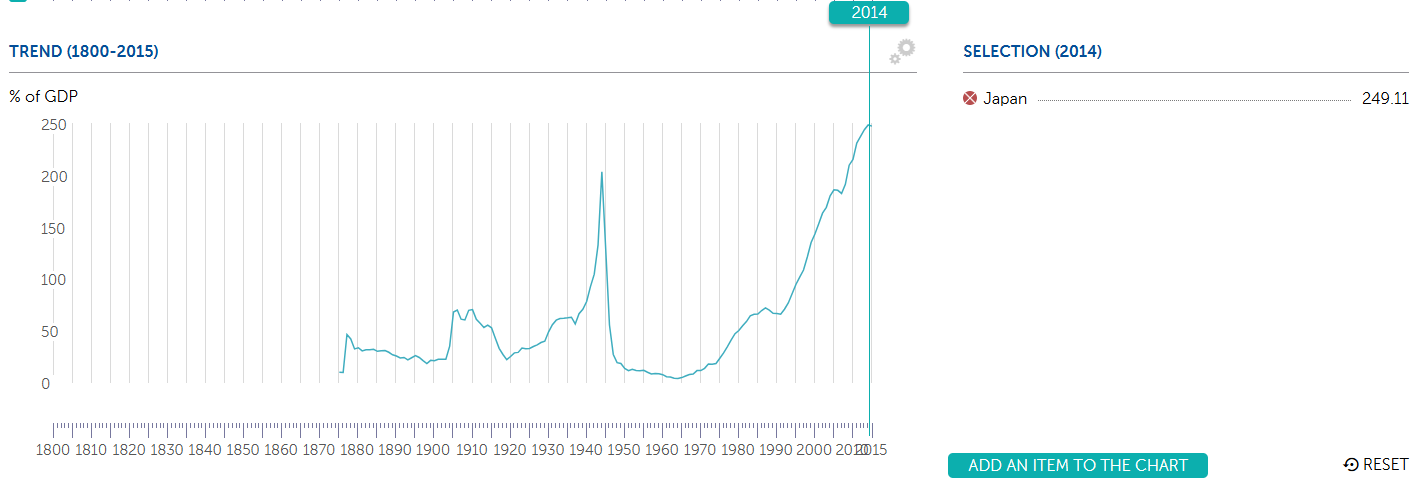

The debt trap and the limits of fiscal policy

Japanese public debt is approaching 250% of GDP, a record among developed countries. While most of this debt is held by domestic creditors, notably the Bank of Japan (BoJ), which holds 53% of sovereign debt, according to Economics Help, the recent rise in interest rates is beginning to drive up the cost of servicing the debt.

Source: IMF

Shigeru Ishiba’s government is therefore faced with a dilemma: support activity via massive fiscal stimulus packages (the latest budget amounts to 114,000 billion Yen), or embark on fiscal consolidation to preserve debt sustainability. In a tense electoral context, the trade-off is politically explosive.

The Japanese bond market: The end of a world?

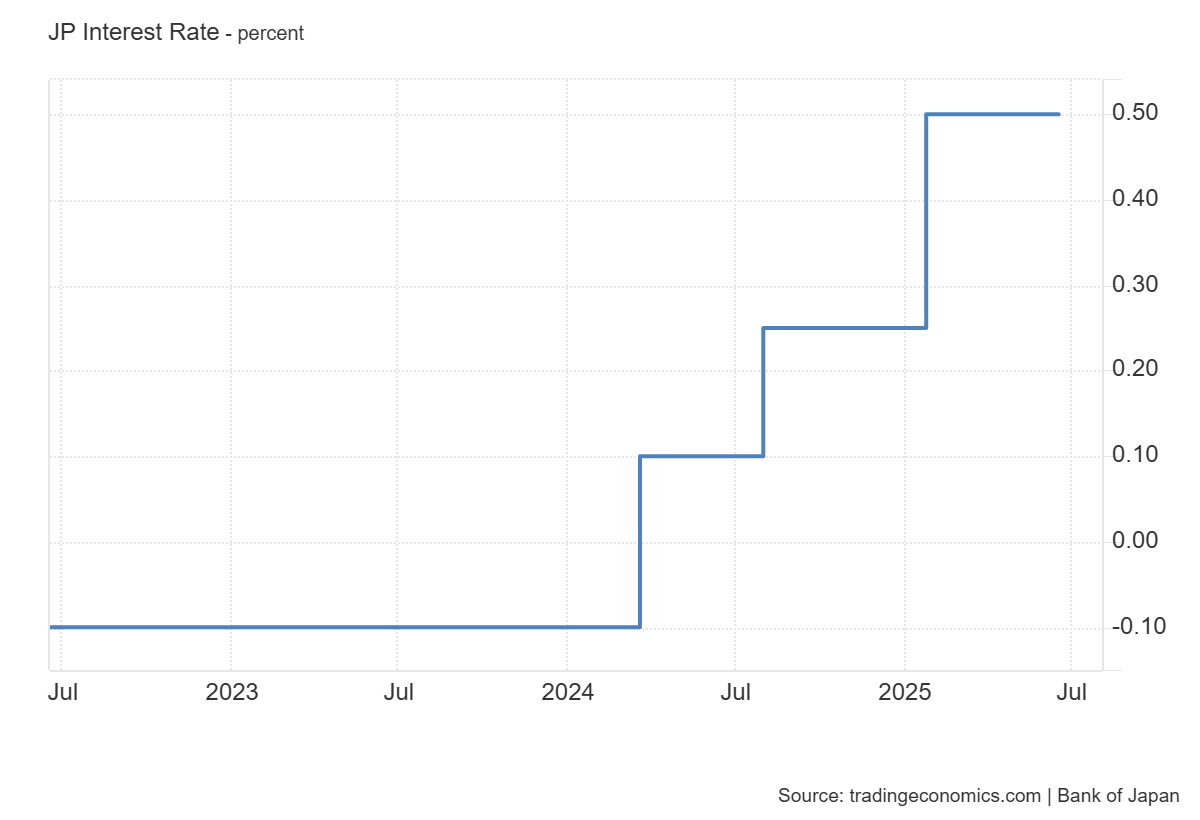

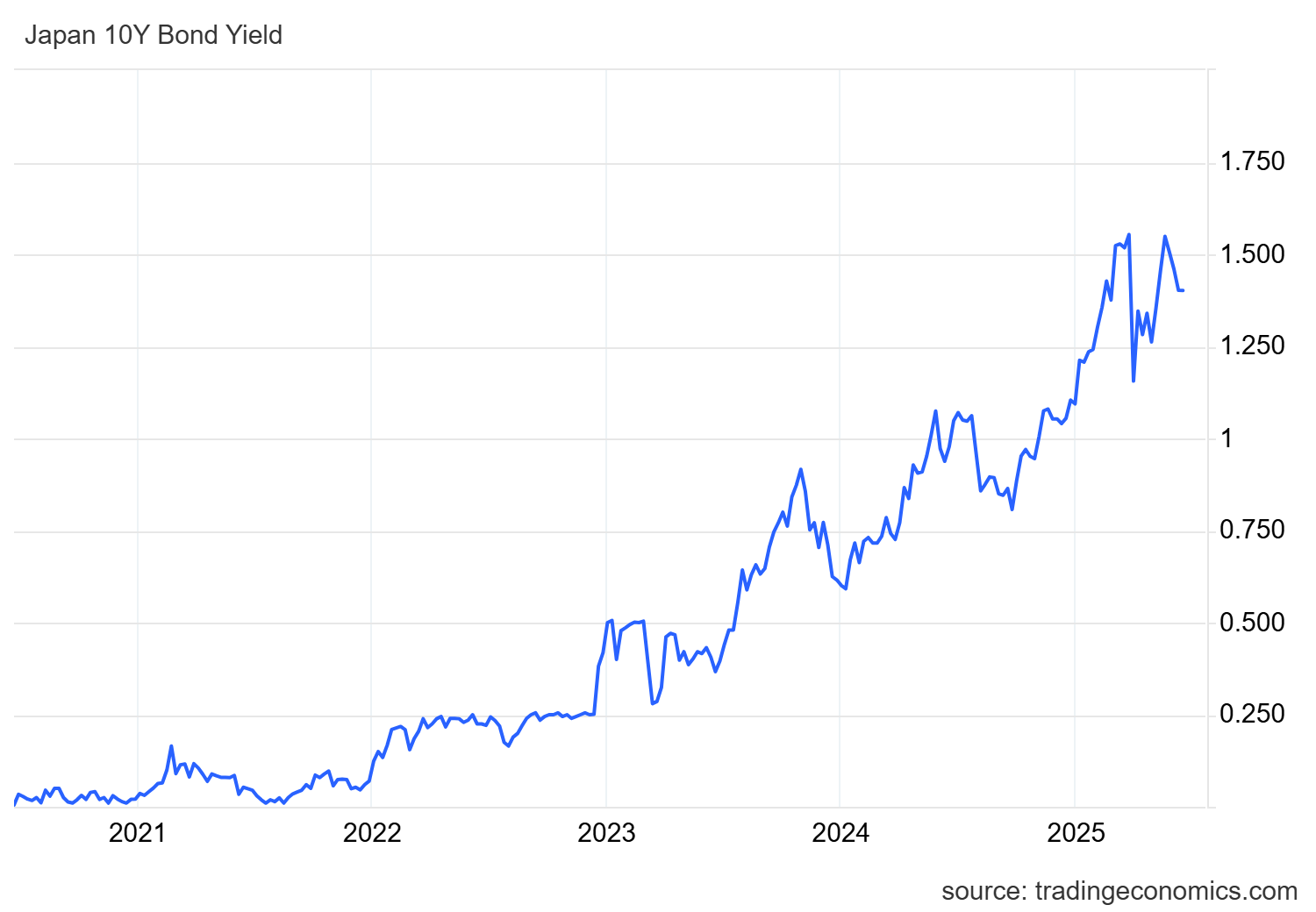

Since 2023, the Bank of Japan has initiated a historic shift away from its ultra-accommodative monetary policy. The key rate was raised to 0.5% in January 2025, and the BoJ reduced its purchases of sovereign bonds, leaving the market to regain its rights.

The effects were not long in coming: the yield curve steepened, yields on 10-year JGBs (Japanese Government Bonds) broke through 1.5%, and 40-year bonds recently experienced lower-than-expected demand at auction, evidence of renewed nervousness.

Even more worryingly, investors are beginning to question the long-term solvency of the Japanese government. While Japan is not at risk of default in the classical sense, the current dynamic is reminiscent of certain warning signs seen in southern Europe in the 2010s.

“Our country’s fiscal situation is undoubtedly extremely poor, worse than Greece’s,” Ishiba said recently, according to Bloomberg.

The Japanese Yen seeks a foothold

On the currency front, the JPY has become one of the great losers of the divergent policies of the major central banks. It has lost almost 30% against the US Dollar in ten years, even though US monetary tightening is beginning to slow down.

USDJPY price chart. Source: FXStreet

The BoJ has tried to support the Japanese Yen through rate hikes, but with no major effect. A weak JPY benefits exporters, but makes energy and raw material imports more expensive. This fuels imported inflation and penalizes domestic purchasing power.

If the Trump administration imposes new trade barriers, the effects on the Japanese Yen could be paradoxical: capital inflows into the JPY as a safe haven on the one hand, but downward pressure from falling foreign trade on the other. The trajectory remains uncertain.

A levitating stock market, despite the real economy

The Japanese paradox is embodied in its stock market. The Nikkei 225 exceeded 40,000 points this year, its highest level since 1989. This boom has been fuelled by share buy-backs and improved corporate governance (reforms inherited from Abenomics), growing interest from foreign investors (notably Warren Buffett), and a weak JPY boosting the profits of multinational exporters.

Nikkei index chart. Source: FXStreet

But this stock market euphoria is disconnected from the real economy. SMEs remain under pressure, productivity is stagnating, and investment remains timid outside sectors such as semiconductors (buoyed by the arrival of TSMC in Japan).

A pending future: Breaking out of the structural trap

Japan remains a stable democracy, a rich economy and a secure, well-equipped society. But its economic potential is hampered by three major obstacles: ageing, a heavy debt burden and low productivity.

To get the ball rolling again, the country will probably have to dare to adopt a radical pro-birth policy (subsidies, parenting aids), free up the entrepreneurial ecosystem (against zombie firms), strengthen its targeted openness to immigration and rethink its energy and industrial policy to reduce dependency.

Japan still has unique human and institutional capital. But at a time when Germany, Korea and India are moving forward, the archipelago must choose: refuse reform in the name of social equilibrium, or face up to its challenges and once again become a powerhouse.

AloJapan.com