The Imperial House of Japan is not a normal family. It is the oldest existing hereditary monarchy in the world, a mysterious clan descended from the gods of Japanese mythology.

The family is also totally powerless, a toothless organ of the government with parliamentarians drawing up new rules for its future offspring.

Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako, long before they ascended to their palace in Tokyo, tried their best to secure a male heir to the Chrysanthemum Throne. They had only one daughter, Princess Aiko.

Crown Prince Fumihito and Crown Princess Kiko had also made a serious effort, giving birth to two more princesses, Mako and Kako. Still, there were no sons.

Bureaucrats were in a panic. Constitutional scholars were sounding the alarm. Royal ladies were infighting, and accusations of blame were filling the imperial court. The prime minister got involved. Government committees were formed. The 2,000-year-old Yamato dynasty was at risk of dying without a male heir in the next generation.

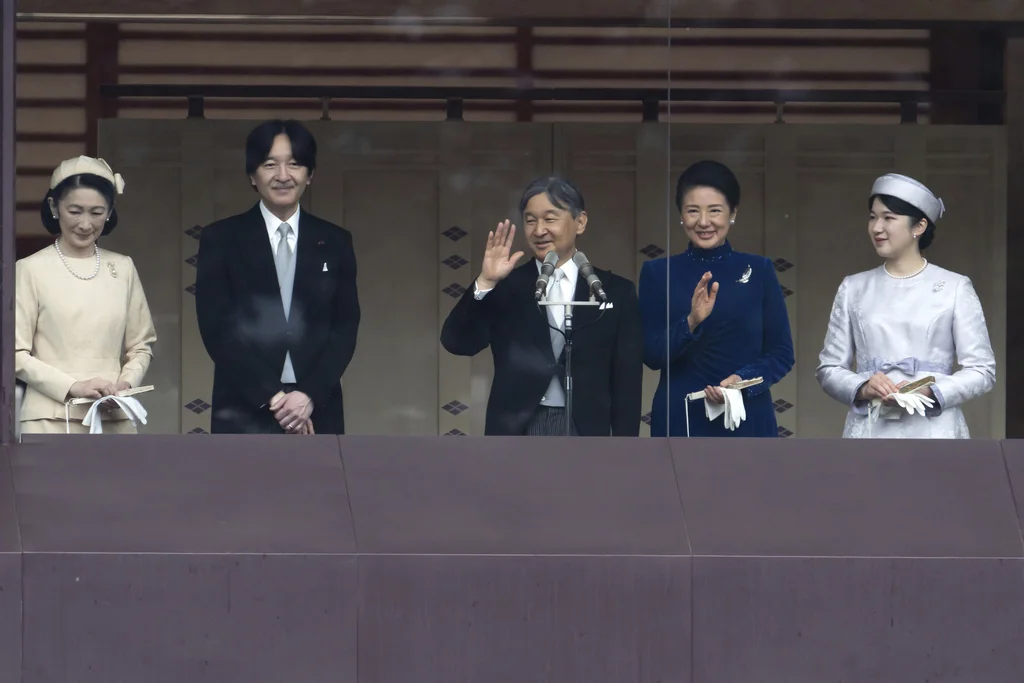

Japanese Emperor Naruhito, center, and Empress Masako wave to well-wishers from the balcony of the Imperial Palace as Crown Princess Kiko, far left, Crown Prince Akishino, and Naruhito and Masako’s daughter, Princess Aiko, far right, look on on Friday, Feb. 23, 2024, in Tokyo. (Tomohiro Ohsumi/Pool Photo via AP)

Japanese Emperor Naruhito, center, and Empress Masako wave to well-wishers from the balcony of the Imperial Palace as Crown Princess Kiko, far left, Crown Prince Akishino, and Naruhito and Masako’s daughter, Princess Aiko, far right, look on on Friday, Feb. 23, 2024, in Tokyo. (Tomohiro Ohsumi/Pool Photo via AP)

Then, in 2006, a miracle arrived at a Tokyo hospital: Kiko gave birth to her third child, Prince Hisahito.

The young prince, now a lanky and somewhat awkward teenager, enrolled at the University of Tsukuba in April. Looming over his studies and extracurriculars is a singular dread. He alone is responsible for continuing the ancient dynasty.

Japanese lawmakers are now close to a breakthrough that will lift that weight off his shoulders and ensure the years of strife and panic that plagued the Imperial Palace will never happen again.

Deities and DNA

The decades of succession concerns prompt an obvious question: Why not let a princess become head of state?

The answer exists at a striking intersection of science and the supernatural — the Japanese royals fiercely protecting specific Y chromosomes they believe were inherited from the descendant of a sun deity in time immemorial.

According to legend, the first emperor of Japan was the warrior-king Jimmu, believed to be the great-grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu. It is for this reason that, in Japanese, the emperor is known as Tenno — the “heavenly sovereign.”

Historical scholars believe he and the eight emperors following him have been mythological inventions, but more concrete evidence of a patrilineal dynasty is documented beginning with Emperor Sujin in the 1st century B.C.

In this photo provided by the Imperial Household Agency of Japan, Japanese Prince Hisahito speaks at his first press conference on Monday, March 3, 2025, at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. (Imperial Household Agency of Japan via AP)

In this photo provided by the Imperial Household Agency of Japan, Japanese Prince Hisahito speaks at his first press conference on Monday, March 3, 2025, at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. (Imperial Household Agency of Japan via AP)

For over 2,000 years, the Chrysanthemum Throne has been passed from male to male within that same ancient family. The protocol for selection has varied, sometimes rotating across multiple brothers of the same generation or jumping across family trees to cousins, but always theoretically connecting back to the same common ancestor: Jimmu.

Particularly cunning or politically convenient women have infrequently maneuvered into the halls of power, but these female monarchs have served mostly as short detours during times when a male crown prince was either too young or too weak to stand on his own.

However, there has never been a male emperor descended from a female line, as their lack of descent from a male emperor would have been seen as illegitimate.

When Emperor Meiji the Great modernized the Japanese Empire at the turn of the 20th century, the household instituted strict agnatic primogeniture to mimic contemporary arrangements among Europe’s royal families.

In modern times, this patrilineal genetic heritage is symbolized by the Y chromosome, the sex chromosome exclusively transferred from fathers to sons.

Such a complex scientific concept would have been unknown in premodern royal courts, but Japanese traditionalists see it as concrete evidence for timeless tradition — to remove gender restrictions from the succession process would ultimately lead to the loss of this unchanged, 2,000-year-old chromosome.

Rearranging royalty

Members of Parliament taking part in the development meetings are coming together on the idea that male relatives from the collateral branches of the imperial family, stripped of royal status by the U.S. military occupation after World War II, may be adopted into the emperor’s household if the throne is without a suitable heir.

Japanese Emperor Naruhito, center, Empress Masako, second right, and other royal family members walk down a hill to greet guests during the spring garden party on Tuesday, April 22, 2025, at the Akasaka Palace imperial garden in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama, Pool)

Japanese Emperor Naruhito, center, Empress Masako, second right, and other royal family members walk down a hill to greet guests during the spring garden party on Tuesday, April 22, 2025, at the Akasaka Palace imperial garden in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama, Pool)

Before the end of World War II, imperial highnesses were in abundant supply. Over the course of centuries, 11 agnatic branch families were established with documented patrilineal connection back to the ruling household. When the main family began dying out and failed to produce an heir, the branch families were always there to lend a male with the right genetic pedigree for adoption.

Following the collapse of the Empire of Japan, the United States allowed the emperor to remain as head of state. Occupation authorities believed the execution or removal of the sovereign could so severely traumatize the already dispirited public that it could lead to mass suicides.

The same grace was not extended to the dozens of collateral princes and princesses, who were stripped of their royal status and rendered commoners. The imperial family was cut down to only then-Emperor Hirohito and his immediate kin.

This sudden change to the imperial structure was the genesis of the 21st-century succession crisis.

Branch families have taken their commoner status in stride but have always made clear that they were ready to jump back into the royal lifestyle if requested.

“We would have no choice but to follow if the emperor, as well as the government, tells us to return to the imperial family,” former Prince Hiroaki Fushimi, 93, said in a 2022 interview.

The suggested carve-out for adoption of collateral princes into the imperial family, if adopted, would create a failsafe to prevent future succession crises.

Radical reformers hoping to see the possibility of a female monarch in the future will almost certainly be disappointed, but the women of the imperial family do stand to gain from the reforms.

Japanese Emperor Naruhito stands as he opens an extraordinary session on Thursday, Aug. 1, 2019, at the upper house of Parliament in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Japanese Emperor Naruhito stands as he opens an extraordinary session on Thursday, Aug. 1, 2019, at the upper house of Parliament in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Imperial princesses lose their status as royals when they marry a commoner. The U.S. abolished the Japanese nobility in the postwar era, leaving only the imperial family as noncommoners.

The only way for a princess to stay royal is to stay single her entire life or marry a direct relative within her own family — an arrangement no one is particularly interested in pursuing.

The Japanese legislature is preparing to abolish this entanglement and simply allow princesses to stay royal regardless of the status of their spouse. This would keep the family large enough to deploy members to public events without running the dwindling royals ragged.

The Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, the main opposition party, is pushing to also allow the government to selectively grant royal status to the husbands and children of princesses.

The ruling Liberal Democratic Party contends that opening royal status to commoners is just one step down a path that will ultimately lead to the abandonment of patrilineal legitimacy, ultimately discarding the sacred Y chromosome.

With the LDP’s secure grip on the legislature, it is unlikely that there will be any peasant-to-prince stories anytime soon.

A symbol of unity

To those who do not place particular value on tradition, this entire debacle may seem absurd to the point of hilarity.

The imperial family holds less sway over Japanese society than the average salaryman, who at least can vote in elections.

In most constitutional monarchies, the sovereign is functionally ceremonial but enjoys a few hypothetical powers they may or may not choose to utilize.

The Constitution of Japan, written in English by post-WWII occupying forces and only translated into Japanese after the fact, demands the emperor “shall not have powers related to government” and instead “shall be the symbol of the State and of the unity of the People, deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power.”

British King Charles III, right, with Japanese Emperor Naruhito, Empress Masako, and Queen Camilla, pose for the cameras ahead of the State Banquet during the State Visit to Britain of the Japanese Emperor and Empress on Tuesday, June 25, 2024, in London. (AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth, Pool)

British King Charles III, right, with Japanese Emperor Naruhito, Empress Masako, and Queen Camilla, pose for the cameras ahead of the State Banquet during the State Visit to Britain of the Japanese Emperor and Empress on Tuesday, June 25, 2024, in London. (AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth, Pool)

The emperor’s power is purely cultural and spiritual.

Owing to his mythological genealogy, the emperor is considered the highest authority in Shinto, the native religion of the island. A portion of his calendar consists of religious ceremonies, such as the Daijosai — a secretive thanksgiving ceremony in which the monarch offers up a fresh crop of rice to Amaterasu.

He is also the guardian of traditional culture, hosting events celebrating antiquated art forms such as poetry readings and Japanese equestrianism. He is also a patron of sumo, the oldest organized sport in the world, with a top prize known as the Emperor’s Cup.

As head of state, he is deployed to foreign nations as the arch-ambassador of Japan and welcomes foreign leaders visiting Japan to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

Regardless of distinctions between unifying the people and leading a nation, the imperial role is a stressful one.

Before taking the throne, Naruhito penned a memoir about his longest time overseas. Titled The Thames and I, the book describes his years as an exchange student at the University of Oxford as the happiest years of his life.

The Japanese legislature may soon confirm and enact the succession policies that will allow teenage Hisahito to no longer worry about the necessity of bearing a son, but there is no legal arrangement that will make his inevitable time on the throne any less exigent.

JAPANESE AGRICULTURAL MINISTER RESIGNS AFTER SAYING HE ‘NEVER BOUGHT RICE’

During his debut press conference in March, the young prince told reporters he believes the ideal emperor is one who is “always thinks of the people” and “stays close to them.”

The Japanese government would agree, with the qualification that a certain Y chromosome is also a prerequisite.

AloJapan.com