CNN

—

In 1970, when the World Fair came to Asia for the first time, Shin Takamatsu was just a student.

The aspiring architect was studying at Japan’s Kyoto University while supporting a wife and young child, but he desperately wanted to be involved. This was, after all, one of the foremost architectural showcases in the world: over its history, iconic landmarks including the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, and the Space Needle were first displayed at the event.

So when he heard that the event’s construction site in nearby Osaka needed bulldozer drivers, he jumped at the chance, quickly getting his license and taking up a lucrative part-time job that gave him a front-row seat to watch the expo come to life.

“It was an exhilarating feeling to be in the middle of a tremendous creative phase,” Takamatsu recalled. “Many dazzling, futuristic buildings were being constructed. But as I watched them, I felt that something was missing.”

As a student, he didn’t know exactly what that was. But the experience stayed with him, and over the years, it shaped his approach to architecture.

“I came to realize that the future cannot be envisioned solely by looking forward. By looking toward the past and interpreting and understanding it, we can develop a perspective on the future,” he said.

In his latest project, his architectural philosophy and personal story come full circle: at Expo 2025 Osaka, Takamatsu returns to the event as the architect behind one of its most striking buildings.

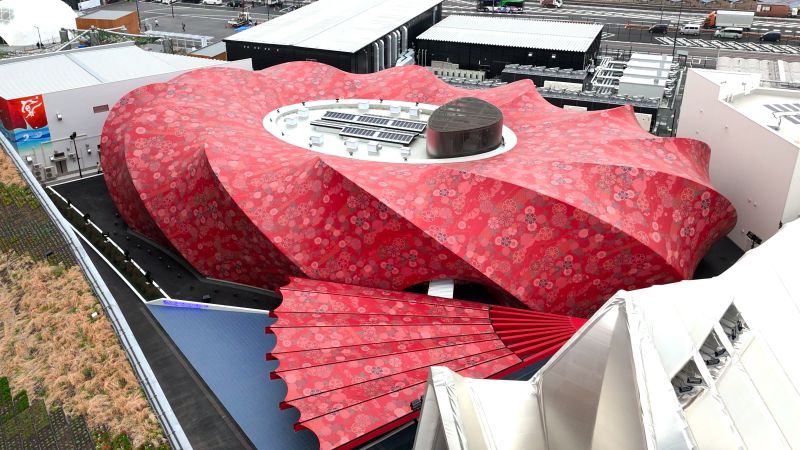

The pavilion — run jointly by housing company Iida Group and Osaka Metropolitan University — is modeled after a Möbius strip, which “continues endlessly in a single loop,” and reflects “reincarnation or sustainability,” explained Takamatsu.

The pavilion looks like a delicately wrapped gift box, covered in a vibrant red, cherry blossom-adorned Nishijin brocade — a traditional textile that has been woven in Kyoto for 1,500 years and is typically used for luxury goods, like kimonos and obis, a kind of belt sash.

Over 3,500 square meters (37,600 square feet) — the equivalent area of more than eight basketball courts — of the handmade silk material covers the pavilion’s exterior, setting a Guinness World Record for the largest building wrapped in Jacquard fabric — a material with the design woven directly into the textile — and another for the largest roof in the shape of a fan.

For Takamatsu, the historic textile represented the perfect way to bridge the past and future.

“It is the culmination of techniques that have been continuously refined over those 1,500 years,” he said, adding that architecture like this “cherishes history and traditions, while proposing a future based on them.”

While the use of fabric in architecture is uncommon, textiles have been used in manmade structures for tens of thousands of years.

Bedouin tents in the Middle East, Native American teepees, and yurts in the Steppes of Central Asia and Mongolia are all examples of nomadic, semi-permanent structures where fabric provides warmth and protection from the elements, while being lightweight and flexible enough to carry.

But modern architects have been reluctant to use fabric in construction, said Sukhvir Singh, a design professor and textiles expert at Shree Guru Gobind Singh Tricentenary University, in India, which he attributes to a lack of familiarity with the materials and their technical properties.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that architects began experimenting with fabrics: German architect Frei Otto was one of the pioneers of lightweight architecture, and at Expo 1967, hosted in Montreal, his design for the German Pavilion used a tensile steel structure to support a lightweight polyester canopy, leading to its nickname, “the floating tent.”

Since then, textiles have been used frequently in temporary structures for major events, such as the Olympics or World Expos. “During these mega gatherings, we have less time, and we have to erect many buildings as soon as possible,” explained Singh, adding that textiles, which are lightweight and are largely prefabricated off-site, are often the obvious solution because of their low cost, flexibility, and ease of installation.

And there’s been a lot of development in the strength and durability of fabrics in recent decades, with carbon fiber-enhanced fabrics that “are stronger than steel,” as well as “high-performance textiles” that can provide added functionality to building facades, such as self-cleaning or energy harvesting, said Singh.

But using handmade silk brocade is quite different from using synthetic polyesters, and there were many technical challenges to overcome for Takamatsu’s pavilion. For example, the textile is “weak against rain, typhoons, and wind,” so it had to be given a special coating and insulating layers to make it fire and climate-resistant, explained Takamatsu.

The fabric was made by HOSOO, a company that’s been weaving Nishijin brocade since 1688. Takamatsu approached Masataka Hosoo, the 46-year-old, 12th-generation president of the family business, about four years ago — who was eager to take on the “unprecedented challenge” of transforming a heritage textile into an architectural structure.

“In fact, I had been nurturing the idea of architectural textiles for over a decade,” explained Hosoo.

Nishijin brocade had been declining in demand for decades: in 2008, sales of the fabric had fallen by 80% from 1990. Hosoo saw the need to adapt his family business to modern consumers’ needs.

So in 2010, the company developed “the world’s first loom” capable of weaving Nishijin textile with a width of 150 centimeters (58 inches), nearly five times the typical width, according to Hosoo.

“Expanding this technique to a much wider format was a significant challenge, requiring extensive innovation and technical precision,” he added.

The larger loom enabled the company to apply its fabric beyond kimonos, into products such as cars, camera accessories, and furniture, and has led to collaborations with luxury brands like Gucci and Four Seasons.

When it came to weaving the brocade for the pavilion, the larger loom was essential — and even then, it still took a team of multiple artisans and engineers two years to produce the required volume of fabric.

“The shape itself isn’t that difficult, but because it’s a form that writhes like a dragon, each part has to be bent, and no piece is identical,” said Takamatsu. To help with this process, HOSOO developed proprietary 3D software that could map out the textile, aligning the pattern precisely across the complex curves of the building.

“The possibilities for textiles are limitless. We’re excited to further explore how textiles can transform architecture and expand into entirely new domains,” said Hosoo.

The Expo in Osaka will run for six months, through to October 13 — at which point, the future of the kimono fabric-covered pavilion is unknown.

Historically, Expo pavilions are “momentary” pieces of architecture that are often dismantled. Some architects lean into that, with eco-friendly construction materials that can be recycled or biodegrade quickly, or modular designs that are easy to disassemble and rebuild.

On the other hand, some structures have become so iconic, they’ve outlived their intended six-month lifespan by decades: the Crystal Palace, which housed the inaugural World Expo in London in 1851, was relocated after the exhibition and remained standing for more than 80 years; and the “Atomium,” the flagship structure of the 1958 expo in Brussels, Belgium, was so popular that the city decided to keep it, renovating the monument in 2006.

A look inside Osaka’s latest World Expo

A look inside Osaka’s latest World Expo

04:28

In terms of engineering, “creating architecture that only lasts six months is the same as creating one that lasts 100 years,” said Takamatsu. So while the future of the brocade-covered pavilion is uncertain, Takamatsu hopes it will be relocated to a permanent location, such as the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

Looking around the Expo site, Takamatsu is heartened by the varying responses to the event’s theme, “Designing Future Society for Our Lives.” Whether the buildings live on or not, the ideas behind them will — which Takamatsu hopes will inspire a generation of architects, just as they did him in 1970.

“It’s not just one design, but rather, various designs resonating with each other, creating a future that sounds like a symphony. I believe this is the greatest message of this pavilion, as well as the many other pavilions at the Expo.”

AloJapan.com