In honor of Shavuos, a Yom Tov associated with geirim, From the Margins of Chabad History explores fascinating stories of geirei tzedek with a Chabad connection, from isolated Russian villages to Tokyo, Japan.

By Shmuel Super

Introduction

Shavuos is a Yom Tov associated with geirim, as this is the day when our ancestors “converted” to Judaism by accepting the Torah and entering into a covenant with Hashem. This is one of the reasons given for the minhag to read Megilas Rus on Shavuos (Abudraham, Seder Tefilos Hapesach), because Rus was also a convert. It is therefore fitting to devote the present article to some fascinating stories of geirim in Chabad history.

First, some historical background. Under the laws of the Russian Empire, conversion to Judaism was strictly forbidden and severely punished. As a result, it was rare for non-Jews to seek to convert to Judaism, and rabbonim were also afraid to perform conversions.

The Russian government censor even prohibited the mention of conversion to Judaism in print. To satisfy the censor, discussion of geirus in Halachic works had to come with a clarification asserting that these laws aren’t actually practiced in the current time and place. For example, editions of the Shulchan Aruch published in the Russian Empire added a note to hilchos geirus in Yoreh Deah, siman 268, stating “these halachos are practiced in countries where the government allows conversion.”

The lines about gerim in a manuscript copy of the maamar, Agudas Chasidei Chabad, ms. 77, p. 74.

The lines about gerim in a manuscript copy of the maamar, Agudas Chasidei Chabad, ms. 77, p. 74.

Not only in print, but even in writing, rabbonim exercised caution when discussing conversion. When the Tzemach Tzedek in Biurei Hazohar (p. 730) discusses the maamar Chazal that the reason for the galus of the Jewish people was to add geirim, he points out that geirim are quite rare, and then adds, “This is the case even in places and times when the government permitted accepting geirim, how much more so now, when we don’t accept any geirim at all.”

This censorship was not committed by the Russian government, as these maamarim were published for the first time in America in 5738. This is how the maamar was self-censored in manuscript, because even in writing, one had to be careful when discussing conversion.

The Schocken Institute for Jewish Research, ms. 70130

The Schocken Institute for Jewish Research, ms. 70130

In the recently discovered manuscript version of siman 156 from the Alter Rebbe’s Shulchan Aruch, the mitzvah of ahavas hager is worded as “loving a ger who came from a distant land” (seif 5). This is clearly an attempt to placate the censor by presenting a ger as someone who must have immigrated from another country, where the government allowed this. Nevertheless, the capricious Russian censor of the Shulchan Aruch was not satisfied, and struck out the entire passage about geirim from the printed edition.

Nevertheless, there were rare cases of geirus in the Russian Empire. In this article, we will survey stories and testimonies about conversion with a Chabad connection.

Sipurei Chasidim

We begin with two stories from the early generations of Chabad that illustrate the dangers of conversion in the Russian Empire.

Our first story appears in Shemuos Vesipurim, vol. 2, story 84. This volume contains stories that the editor R. Foleh Kahn collected from various sources, which he lists in the introduction. However, this story is part of a unit in the book for which the source is not referenced. Here is the story, in English translation:

R. Aryeh, a chasid of the Alter Rebbe, was the government-appointed town official, known as the “burgermeister.” This position was similar to that of the rav mitaam—the registry books for marriages, births, and—lehavdil—deaths, were all under his authority.

Once, a non-Jew converted to Judaism in a certain place. In an attempt to protect the convert and those involved in the conversion, R. Aryeh was asked not to record the death of a Jewish man who had just passed away and happened to be the same age as the convert. This would enable them to give the convert the deceased person’s documents and identity, thereby safely resolving the matter.

R. Aryeh acceded to the request. However, someone informed on him to the government, and he was arrested. Facing a trial, he was in grave danger.

R. Aryeh traveled to the Alter Rebbe. The Alter Rebbe asked R. Aryeh when the trial was scheduled, and R. Aryeh told him the date.

The Rebbe said, “It would be worthwhile to try to postpone the trial date.” R. Aryeh was successful in doing so.

When the second date approached, R. Aryeh traveled to the Rebbe again, and once again the Rebbe advised him to try to postpone the trial. This repeated itself several more times.

Finally, R. Aryeh told the Rebbe that he could no longer delay, and the trial would soon take place.

The Rebbe said to him: “The wedding of my grandchild with the grandchild of the holy Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev is approaching soon. Come to the wedding and try to approach my mechutan and tell him about your situation. He will certainly help you.”

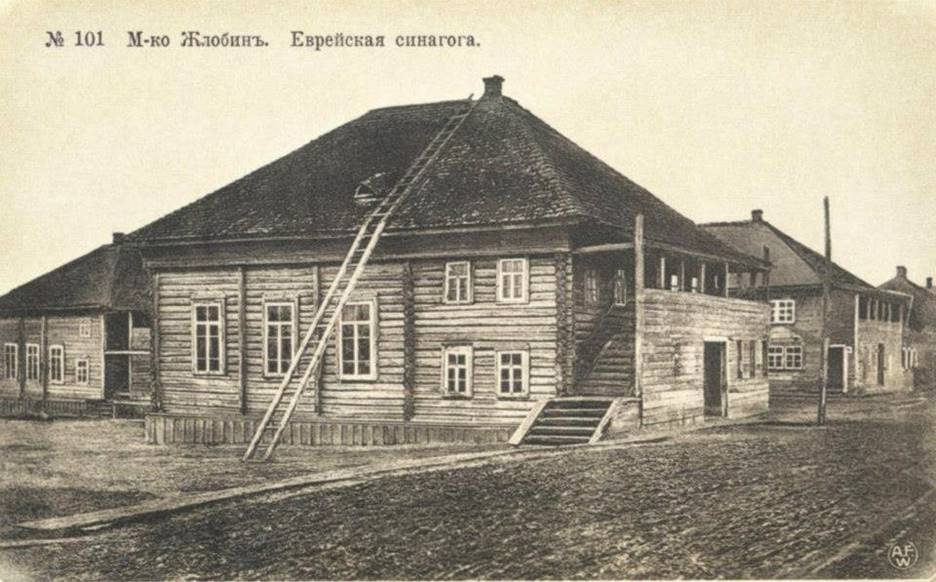

A shul in Zhlobin, c. 5660

A shul in Zhlobin, c. 5660

R. Aryeh did as he was advised. He came to Zhlobin, where the wedding was held, and tried to approach R. Levi Yitzchak. But thousands of people were surrounding the house where the tzadik was staying, and it was impossible to enter.

Seeking a way to get in to see the tzadik, R. Aryeh decided to come back after midnight and wait at the entrance to the tzadik’s room, hoping to be the first to enter the next day.

He came at night and saw R. Levi Yitzchak lying in his bed. Two gabaim stood on either side of the bed, one holding a Mishnayos and the other holding a Zohar. They were reading simultaneously, one from the Zohar and the other from the Mishnayos, while the tzadik appeared to be asleep. But when one of the gabaim made a mistake, the Rebbe turned to him and said, “nu, nu.” This went on for about two hours. R. Levi Yitzchak then rose from his “sleep,” and the gabaim allowed R. Aryeh to enter.

When R. Aryeh entered, the Rebbe asked him who had sent him here. He replied, “My Rebbe.” R. Levi Yitzchak asked him who his Rebbe was, and he mentioned the Alter Rebbe’s name. “Ah, the mechutan! He’s your Rebbe?” R. Levi Yitzchak exclaimed. “The mechutan, the tzadik, the gaon, the ish Elokim!” R. Levi Yitzchak continued. He repeated himself several times, each time with different praises for the Alter Rebbe, all with a warm and loving demeanor.

R. Levi Yitzchak then turned to R. Aryeh, nu, sertze, tell me, what do you want?” (Sertze is Russian for “heart,” a term of endearment R. Levi Yitzchak often used.) R. Aryeh said that he was a burgermeister, and explained his predicament. The tzadik asked R. Aryeh what a burgermeister is, and R. Aryeh explained it to him. “What?” the tzadik asked, “A Jew is the town official? How can that be?” R. Aryeh replied, “My Rebbe advised me to accept this position.”

R. Levi Yitzchak then exclaimed, “Ah! So my mechutan, the gaon and tzadik, told you to fill this position. So, nu, Hashem will help you and protect you from all trouble.”

When R. Aryeh returned to the Alter Rebbe and recounted what had happened, the Rebbe said, “Nu, did I give you good advice? Yes?” The Alter Rebbe repeated himself, “I gave you good advice, no?”

In the end, the day before the trial, a fire broke out in the courthouse. All of the documents were burned, including the indictment against R. Aryeh, and he was saved from trouble.

***

Our second chasidishe conversion story takes place during the next generation of Chabad, the time of the Miteler Rebbe. There are a few versions of this story, with differences between them. We will use the version published by R. Yehudah Chitrik in Reshimos Devarim (pp. 113–114), in the name of the mashpia R. Groinem. A discussion about the story and other versions of it appears in R. Yehoshua Mondshine’s introduction to Shut Zecher Yehudah, pp. 8–9.

The gaon and chasid R. Zalman Zezmer once spent Shabbos in Lubavitch during the nesius of the Miteler Rebbe, and heard a maamar chasidus from the Rebbe. Back at his lodgings, R. Zalman commented to some people that he had not heard any novel insights in that day’s maamar.

Gossipers reported R. Zalman’s words to the Miteler Rebbe. The Miteler Rebbe was very displeased, and exclaimed: “He says there was nothing new in the maamar? I’ll send him to Siberia!”

Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, ms. 173, p. 109. The text reads:

Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, ms. 173, p. 109. The text reads:

“A copy of the recommendation R. Hillel wrote to the city of Repke on behalf of R. Zalman Zezmer’s son.

“Had you known his late father of blessed memory you would certainly make every possible effort to assist him, as the pasuk states, ‘I have not seen a tzadik forsaken.’ For there was none like him before, and I haven’t yet seen anyone like him since, an oved Hashem with mind and heart. His heart was like that of a lion, and his understanding of the depths of the Divine light was vast, elevation after elevation, with no limit.”

Some time later, the people of the town of Paritch were looking for a rov. R. Zalman was interested in the position, but he knew that the Miteler Rebbe had a kpeida on him. He therefore asked the great chasid R. Hillel Paritcher to advocate for him to the Rebbe. R. Hillel was one of the chasidim who had been brought to Chabad by R. Zalman.

When R. Hillel suggested to the Miteler Rebbe that he send R. Zalman to serve as the rov of Paritch, the Rebbe said: “I should send him to Paritch for the rabbonus? I’ll send you to Paritch!”

In his final years, R. Zalman lived in the town of Krislava. He and two other rabbonim performed a giyur for a woman, an act that was forbidden according to the government’s laws. They were reported to the authorities, put on trial, and R. Zalman was sentenced to exile in Siberia.

Just a few days before the government officials came to carry out the sentence, R. Zalman passed away and was buried in Krislava. When the officer came to take R. Zalman and chain him up and send him to Siberia, he was told that R. Zalman had passed away and had been buried. The officer refused to believe them. They were forced to open the grave and show him that R. Zalman was indeed buried there.

In this way, the words of the Miteler Rebbe were fulfilled, and the zechus of R. Zalman stood by him, as he was niftar before the sentence could be carried out.

***

The Subbotniks—An Overview

There was one major conversion episode of conversion in the Russian Empire—the Subbotniks. However, the details of this case are shrouded in mystery and still debated today. The following is a basic outline of the Subbotnik story, based on the information collected in the kuntres Shabbos shel Mi.

Around 5530 (1770), a group of Russian Orthodox Christian peasants in the Voronezh region broke away from Christianity. They believed only in the books of the Tanach, and they refused to participate in Christian ceremonies, which they considered idolatrous. They observed a day of rest on Shabbos, earning them the name “Subbotniks” (Subbota is Russian for Shabbos).

The Russian authorities cracked down harshly on this sect of what they called “Judaizers.” The crackdown was initially successful, but a few decades later, in 5574 (1814), reports came that the sect was spreading again in villages in the Voronezh area. Their numbers were estimated at 20,000.

The authorities responded with even harsher decrees, including conscription to military service and exile to Siberia. The persecution forced the sect underground, with many continuing to practice their unique customs in secret.

At this time, Jews in the Russian Empire were officially restricted to living within the “Pale of Settlement.” Voronezh was well beyond the pale, so there were no organized Jewish communities in the area. However, Jewish merchants did occasionally pass through the region and may have had some degree of contact with these Judaizers.

A Subbotnik, c. 5673

A Subbotnik, c. 5673

In 5647 (1887), the Russian government officially recognized the Subbotniks as an independent religious sect and allowed them to conduct their practices openly. During this period, more Jews were passing through the area, and the Subbotniks engaged with them to learn more about Jewish practices. By this time, many Subbotniks considered themselves Jewish, and they adopted practices they learned from Jews. They began to wear tzitzis and tefillin, grew beards, celebrated yamim tovim, obtained sifrei Torah, and studied Hebrew.

But were these “Judaizers” actually Jewish? To become Jews, they would need to have undergone a halachic conversion, but it is unclear to what extent this happened. Of course, considering that giyur was strictly forbidden, we can’t expect to find documented evidence of it even if it did occur.

It seems that, over time, at least some Subbotniks did undergo proper giyur by real rabbonim, but it is hard to conceive of mass giyur being conducted for entire groups. It is also possible that unlearned Jews performed some kind of unauthorized conversion for them, which would have dubious halachic status.

The halachic status of the Subbotniks continues to be debated by contemporary poskim, with most requiring them to undergo a giyur, at least lechumra. The kuntres referenced above is one of the recent publications on the topic.

The birth of the Subbotnik sect and the rise of Chasidus Chabad occurred at roughly the same time. Although the movements were geographically very distant, there was sporadic contact between them.

Fascinatingly, the Chabad mekubal and innovative thinker R. Chaim Eliezer Bichovsky even speculated about a spiritual link between the genesis of the Subbotniks and the Alter Rebbe. In the context of a discussion about the spiritual powers that attract the neshamos of those destined to be geirim, he writes (translated): “Based on this, we can suggest that the journey of the Alter Rebbe through Russia and his passing there was in order to bring the souls of geirim. I believe that the movement of the Subbotniks to convert occurred at this time” (Kisvei R. Chaim Eliezer Bichovsky, p. 118).

Indeed, R. Bichovsky was correct about the chronology, as the second rise of the Subbotnik sect—and its more “Jewish” phase—began immediately after the Alter Rebbe’s journey into inner Russia, not too far from the Voronezh region.

Geirim Visit Lubavitch

The following account about the encounter of three families of geirim with the Rebbe Maharash and Lubavitcher chasidim was printed in the Hameilitz newspaper of 23 Shevat 5629 (February 4, 1869).

The piece quoted from Kisvei R. Chaim Eliezer Bichovsky in the author’s original handwriting. Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, ms. 307, p. 108.

The piece quoted from Kisvei R. Chaim Eliezer Bichovsky in the author’s original handwriting. Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, ms. 307, p. 108.

In this article, Hebrew writer and later Zionist activist Yehoshua Sirkin reports on his visit to Magdeburg, Germany. In the course of the article, he describes an encounter with a prospective convert in Magdeburg, which leads him to relate an event that occurred the previous year in 5628. Here is the relevant piece, in English translation. The writer’s negative personal opinions about chasidim have been omitted:

Speaking of conversion, I am reminded of what I witnessed last year in Moscow. I saw three Russian families, husbands and wives, all craftsmen, who had come from the city of Kazan, where they had publicly accepted the Jewish faith in the proper way. However, the regional governor expelled them from Russia. They traveled through Moscow to the city of Lubavitch to see the local Rebbe and seek his counsel and advice, and from there they planned to journey to the Holy Land.

When I spoke to them, I realized that they had already encountered Lubavitcher chasidim along their way…

I was astonished to see people whose facial features testified to their origins, wearing long tzitzis that reached their heels, yet davening from their hearts in their own language and reading Tanach in a Slavic tongue, because they could barely read Hebrew. I still don’t know what happened with them subsequently.

The origin of these converts is unclear—Sirkin only tells us that they converted in the city of Kazan, which is east of Voronezh. Kazan was outside the Pale of Settlement, but Jews who had served in the Russian army as Cantonists were allowed to live there, and by 1861, there were 184 Jews there (Encyclopedia Judaica, Kazan). While we can’t know for sure, it seems logical to assume that these converts were Subbotniks.

The Subbotnik and the Shochet

Our next point of contact between chasidei Chabad and the Subbotniks occurs in 5658 in the chasidishe city of Homel. We read about it in the 16 Tamuz 5669 (July 5, 1909) edition of the Haynt newspaper, printed in Warsaw. Over the previous weeks, the Haynt newspaper had carried two articles about Subbotniks (see here and here), inspiring a reader who signs as “D. Moskvin” to send in his memories of meeting a Subbotnik over a decade earlier in Homel.

The chasid featured in this account is R. Leib Chasdan, the chasidishe shochet of Homel, who was a chasid of the Tzemach Tzedek, Rebbe Maharash, and Rebbe Rashab. R. Leib had earlier served as a shochet in the town of Sebezh, giving him the lifelong nickname “the Sebezher shochet.”

R. Leib is the ancestor of the Chasdan family, and information about him and his family appears in the first chapters of the recently published book Chasdei Yisrael, about his grandson R. Yisrael Chasdan. He was also the maternal uncle of R. Zalman Duchman, and several stories he told are recorded in L‘sheima Ozen. Interestingly, R. Leib was a descendant of R. Zalman Zezmer, whose connection to geirim was related above.

Here are the key points of the story the article tells:

In 5658, a large 38-year-old Russian-looking peasant arrived in Homel. He said he came from the city of Rasskazovo, in the Tambov region, where 2000 of the city’s 20,000 are converts who observe Judaism to the best of their abilities.

The man had a Hebrew name, Binyamin ben Kalman, but he only spoke Russian. He was even baki in Tanach, which he read in Russian. He related that his entire community has no access to kosher meat, as none of them are trained in the halachos of shechitah. As the most Jewishly knowledgeable person in town, the community had chosen him to go and study shechitah so that they could all eat kosher meat.

Seeing that the man was sincere, R. Leib the shochet—whom the writer describes as “a passionate Lubavitcher chasid, a lamdan and a baal pilpul”—agreed to teach him. Teaching the Subbotnik to sharpen a chalaf was easy enough, but when it came time to teach the halachos of shechitah, the language barrier was a problem. The Subbotnik didn’t know Hebrew or Yiddish, and R. Leib didn’t know any Russian. The problem was solved by R. Leib’s oldest son, who was more modern and had a secular education. With him serving as the interpreter, the Subbotnik was able to learn the halachos of shechitah within three months.

The visiting Subbotnik did not know any details about the origins of his sect. All he knew was that he had heard from his great-grandfather that in the time of Czar Nikolai I, their group had been persecuted and pressured to return to Christianity, but the more they were oppressed, the stronger they clung to their beliefs.

While in Homel, the Subbotnik would attend shul three times a day for davening, and after davening, he would recite the entire Tehilim as well—all in Russian. He had tefillin, which he wore for shacharis. Living for the first time in a fully educated and practicing Jewish community was a very moving experience for the Subbotnik, and the writer describes how this big Russian peasant cried from emotion when he experienced the beauty and purity of Shabbos at R. Leib’s home for the first time.

Interestingly, from this article and others, it seems that the mainstream Russian Jews did not question or investigate the Jewishness of the Subbotniks. They appear to have simply accepted the people they met as Jewish when they told them that they were part of a community that had converted to Judaism. However, it is possible that they did ask more questions and require a giyur lechumra if a Subbotnik was actually seeking to join their community and marry with them.

Awaiting Mashiach

Our final Subbotnik-related story was told by none other than the Rebbe himself. The Rebbe, known at the time as “the Ramash,” related this story at a farbrengen of chasidim in 770 for Chai Elul of 5706, and it was recorded by R. Avraham Weingarten, a bochur in 770 at the time. This story was published in a Weingarten family teshurah (Wertzberg, 5663, p. 7). Here is a translation:

[The Ramash related] that three Jews with long beards once came to his father in Yekatrinoslav. They came from a village where all of the inhabitants had converted themselves. They said that as there is a war now, it seems that Mashiach will be coming soon. However, they live in a little village, and are afraid that Mashiach won’t pass through their town. Since Yekatrinoslav is a large city, Mashiach will certainly come there, so they are asking the rov to notify them when Mashiach comes.

***

A Japanese Ger Tzedek

Our final convert is more recent—Japanese scholar Setsuzo Kotsuji. Born in Kyoto, Japan, Setsuzo was a descendant of a long line of Shinto priests. In his youth, he became a monotheist and converted to Christianity. His interest in the Bible led him to study Hebrew, and he became a professor of Bible and Hebrew at Tokyo University.

When Japan conquered Harbin, China, Kotsuji became a government envoy to the local Jewish community, and his interest in Judaism deepened. During World War II, thousands of Jewish refugees from Europe arrived in Japan on transit visas, and Kotsuji successfully lobbied and bribed officials to allow them to stay. He worked to counter the anti-Jewish propaganda the Germans were spreading in Japan, and he was arrested and tortured as a result.

Left to right: R. Shlomo Shapiro, Dr. Setsuzo Kotsuji, the Amshinover Rebbe, the Lomza rov R. Moshe Shatzkes, Captain Yuzuru Fukamachi and Leo Hanin outside the Naval Officers Headquarters in Tokyo.

Left to right: R. Shlomo Shapiro, Dr. Setsuzo Kotsuji, the Amshinover Rebbe, the Lomza rov R. Moshe Shatzkes, Captain Yuzuru Fukamachi and Leo Hanin outside the Naval Officers Headquarters in Tokyo.

R. Pinchas Hirschprung, later the rov of Montreal, was one of the refugees in Japan and Shanghai, together with a group of talmidim from Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. He wrote a fascinating Yiddish memoir about his wartime experiences, titled Fun Natzishen Yomertol: Zichrones fun a Polit. The memoir has been translated into English under the title The Vale of Tears. The final chapter of the memoir is devoted to Professor Kotsuji, and we will quote some excerpts from the English translation (pp. 259-261):

While I am on the subject of Japan, I would be remiss if I did not write a few words about the Japanese professor Abram (Abraham) Kotsuji. When we arrived in Japan, a foreign country with a foreign language and foreign way of life, we met a friend of the Jews and a friend of the Torah. He treated us with love and respect and did everything he possibly could to assist us. Thanks to him, Japan was a much more welcoming place for us than we could ever have imagined.

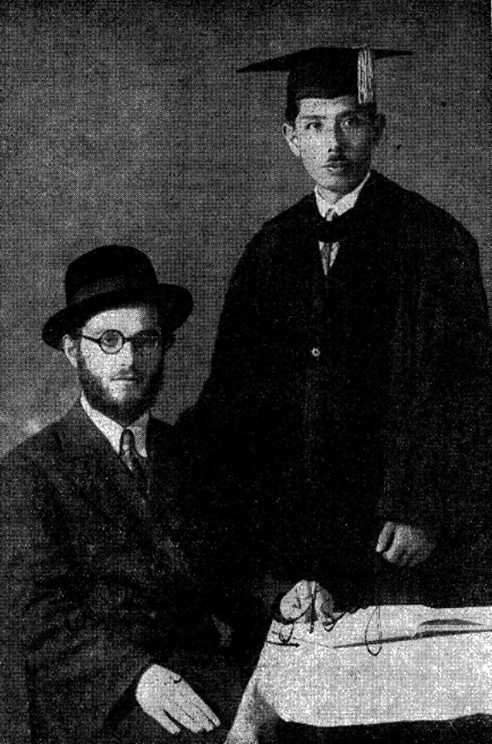

Professor Kotsuji with R. Avraham Mordechai Hershberg in Japan. R. Hershberg (5676–5743) was later the Chief Rabbi of Mexico.

Professor Kotsuji with R. Avraham Mordechai Hershberg in Japan. R. Hershberg (5676–5743) was later the Chief Rabbi of Mexico.

This picture is published in Fun Natzishen Yomertol: Zichrones fun a Polit, p. 246.

Abram Kotsuji, a professor of theology at the University of Tokyo, managed to obtain a temporary permit from the Japanese government for the Jewish refugees to open a yeshiva for the refugee scholars. For the first time in the history of Japan, there were functioning yeshivas in both Kobe and Shanghai. My friend Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Hershberg became a close personal friend of the highly esteemed academic. Before we left Japan, the professor gave him a very valuable gift, a Hebrew textbook that he, Professor Kotsuji, had authored. This book was printed in Hebrew and Japanese in the only Hebrew printing house in Japan, which belonged to Professor Kotsuji’s Department of Theology at the University of Tokyo. It was a textbook for Japanese students.

Professor Kotsuji was so in love with the Hebrew language that he founded the Tarbut Ivrit to enable Japanese scholars to study it. For this purpose, he also had his own special institute in Kamakura where he taught Japanese students theology in the Hebrew language, the Bible in the original. “You, the scholar refugees, have an important mission. You must save the Torah from the conflagration and carry it with you wherever you go. It does not matter to what distant land your journey as a refugee may take you, be it a faraway island in Asia or Africa, or a colony somewhere in South America, you must bring the Torah with you and plant Jewish life there.” That is what the professor told the yeshiva students when we honoured him with a banquet to acknowledge his service to the Jewish refugees, as well as his keen interest in Jewish learning.

Professor Kotsuji assisted the refugees significantly by persuading the Japanese authorities to be lenient in enforcing the terms of the transit visas, thus allowing the refugees to remain in the country longer than stipulated. In Kobe, we were looked after by the Yevkom, a committee founded by the Kobe Jews for the purpose of supporting refugees during their temporary stay. It was in the Yevkom that we first met Professor Kotsuji. He became such a close friend of Rabbi Hershberg that he invited him to his home, took long walks with him, and had a photograph taken of the two of them together.

In the Yevkom, we discovered that prior to our arrival in Japan, Professor Kotsuji, at the request of the Kobe Jewish community, had interceded with the Japanese authorities to extend the transit visas for the refugees. The transit visas had been issued for a short period only – ten days. The refugees, however, needed to remain in Japan for a longer time. Professor Kotsuji used his influence with the Japanese authorities to have the length of our stay extended.

On our ship, there had been seventy-two refugees who did not have visas for Curaçao in the Dutch West Indies, and the Japanese authorities sent them back to Vladivostok. The Yevkom asked Professor Kotsuji to intercede on behalf of these refugees. In response to this request, he managed to get permission for them to enter the country. Even the German radio reacted to the fact that the refugees were being sent back from Tsuruga to Vladivostok. It announced that neither the Soviet Union nor Japan were eager to allow in those “elements” that the Third Reich had “thrown out.” Professor Kotsuji, by his actions, had given the Third Reich a slap in the face.

The yeshivas invited Professor Kotsuji to pay them a visit. He complimented them on their method of study, but one thing, he said, was incomprehensible to him – swaying back and forth during study. “I don’t understand,” he said, “how one can focus one’s thoughts while rocking one’s head up and down.”…

Professor Kotsuji inscribed the Hebrew-Japanese book that he gave as a gift to Rabbi Hershberg with his signature, “Abram Kotsuji.” When Rabbi Hershberg asked him why he had written “Abram” instead of “Abraham,” the professor answered that our ancestor began calling himself Abraham only after he had been circumcised. Rabbi Hershberg then asked him a personal question: Why had he not converted to Judaism? “I can do more for Jews as a true Japanese than if I were to officially become Jewish,” he replied.

***

Professor Kotsuji in Shaarei Tzedek hospital in Yerushalayim where he had his bris milah. He is talking to Professor Yisrael ben Zeev, an advocate for converts to Judaism, who helped arrange his conversion.

Professor Kotsuji in Shaarei Tzedek hospital in Yerushalayim where he had his bris milah. He is talking to Professor Yisrael ben Zeev, an advocate for converts to Judaism, who helped arrange his conversion.

Picture from The Sentinel, November 5, 1959.

R. Hirschprung published his memoir in 5704. Fifteen years later, in 5719, Professor Setsuzo Kotsuji traveled from Japan to Yerushalayim and converted to Judaism, taking the step from a chasid umos haolam to a ger tzedek. He took the Jewish name Avraham.

In Eretz Yisrael, Professor Kotsuji was warmly welcomed by the refugees whom he had helped save during the war, including the rabbonim and talmidim of the Mir Yeshivah.

An article in the Israeli Hatzofeh newspaper reported on Professor Kotsuji’s reception in Eretz Yisrael and his preparations to travel to America for a lecture tour. Interestingly, this article points to a close connection with Chabad, reporting that the professor had davened at the Chabad shul in Yerushalayim, had been hosted by R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin for Shabbos meals, and spent a few days in Kfar Chabad. The article also says that Kotsuji will be greeted in America by emissaries of the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Hatzofeh, 5 Kislev 5720 (December 6, 1959).

Hatzofeh, 5 Kislev 5720 (December 6, 1959).

Courtesy of the Historical Jewish Press website—www.Jpress.org.il—founded by the National Library and Tel Aviv University.

Indeed, in his autobiography From Tokyo to Jerusalem, Kotsuji mentions that he visited Kfar Chabad in 5719, where he met two old Jewish friends from Japan, “a certain Plotkin and Joseph Moiseef” (p. 195).

Recently, a letter of the Rebbe to Professor Yisrael ben Zeev, an advocate for converts to Judaism and an anti-missionary activist in Eretz Yisrael was sold at an auction. Ben Zeev had helped arrange Kotsuji’s giyur in Yerushalayim, and in this letter, a few years later in 5724, the Rebbe writes to him about assisting Professor Kotsuji’s wife to undergo conversion.

The Rebbe writes that he had spoken to Professor Kotsuji about this directly in the past, but the matter had not advanced.

In the diary of 770 yeshivah bochur Yisrael Yoel Sosover from 1 Tammuz, 5626, he records that “the rabbi from Australia” had a fifty-minute yechidus with the Rebbe that night, and that one of the requests the Rebbe made of him was to attempt to have “the wife of the ger tzedek” convert—clearly referring to Mrs. Kotsuji.

The Rebbe’s letter to Professor Ben Zeev about Professor Kotsuji, dated Rosh Chodesh Shevat, 5724.

The Rebbe’s letter to Professor Ben Zeev about Professor Kotsuji, dated Rosh Chodesh Shevat, 5724.

Perhaps the reason the Rebbe was so interested in Mrs. Kotsuji converting was because the professor was aging and needed assistance.

The source and extent of Professor Kotsuji’s relationship with the Rebbe and Lubavitch remains unclear. Family members of the Lubavitcher bochurim who spent time in Japan whom this writer spoke to were unable to shed light on the matter. If any readers have additional information on this topic they are encouraged to share it with us.

Professor Kotsuji spent a decade at the end of his life in New York, where the grateful Jewish community assisted him as he aged. He then returned to Japan, and passed away shortly thereafter on 6 Cheshvan 5734. He was buried in Yerushalayim.

To view all installments of From the Margins of Chabad History, click here.

AloJapan.com