A central Japan aquarium offers a rare glimpse of sea otters floating on their backs and using rocks like masterful chefs to crack open clams, mussels and other shellfish treats.

However, unfortunately, the opportunity is nearing its end and signaling wider concern for the species.

People flock every day to the Toba Aquarium in Mie Prefecture to see the last two remaining sea otters in captivity in Japan. They hope to get an up-close look at the cute mammals and their playful antics.

Kira (L) and May, the only two captive sea otters left in Japan, are pictured at Toba Aquarium in Toba, Mie Prefecture. (Photo courtesy of Toba Aquarium)(Kyodo)

In recent years, the wild sea otter population has plummeted as hunters have targeted the animal for its dense and valuable fur. The situation is made even more dire when combined with environmental pollution, including the aftereffects of the massive Exxon Valdez ocean tanker oil spill off the coast of Alaska in 1989 that killed them in their thousands.

Breeding in captivity has also been challenging, and experts are sounding alarm bells about the species’ future.

May, a sea otter, jumps to reach food at Toba Aquarium in Toba, Mie Prefecture.(Photo courtesy of Toba Aquarium)(Kyodo)

“People should not only love sea otters but also pay attention to why they have become an endangered species,” advised one expert.

At the aquarium in the city of Toba, the two sea otters — 21-year-old May and 17-year-old Kira — are by far the most popular attraction.

Photo taken on March 20, 2025, shows a line of patrons waiting to see sea otters at Toba Aquarium in Toba, Mie Prefecture. (Kyodo)

They are the only sea otters remaining in a Japanese aquarium or zoo after the death in January of Riro, who was 17, at Marine World Uminonakamichi in Fukuoka, southwestern Japan.

The average lifespan of sea otters in captivity is typically around 20 years. With both May and Kira being female, breeding is not an option and imports of sea otters also ceased in 2003 due to international restrictions.

According to the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the number of sea otters in captivity in Japan peaked at 122 in 1994. Since then, their numbers have steadily declined as breeding has proven difficult and mothers have suffered lactation issues, causing problems with feeding the pups that have been born.

Opened in May 1955, the Toba Aquarium is celebrating its 70th anniversary this year. It is making painstaking efforts to keep May and Kira healthy and alive as long as possible.

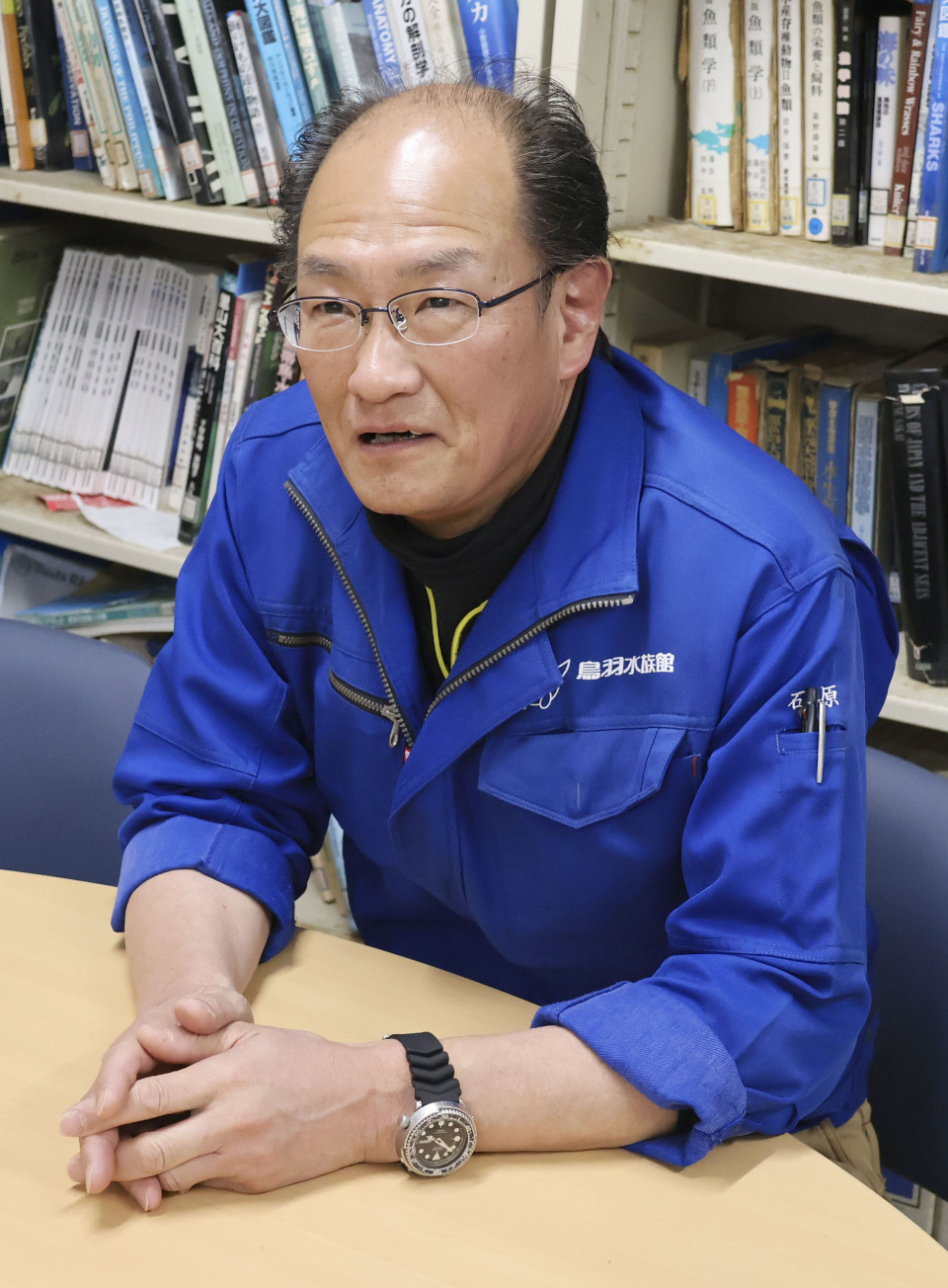

Yoshihiro Ishihara, a keeper at Toba Aquarium, is pictured on March 20, 2025, in Toba, Mie Prefecture.(Kyodo)

Breeder Yoshihiro Ishihara, 64, has devised a creative way to encourage them to exercise during feeding. He attaches squid fins high inside the sea otters’ enclosure so they are forced to jump and extend both paws to grab their food. In this way, Ishihara can determine their muscle condition and cognitive ability.

In an effort to allow as many people as possible to see May and Kira, the aquarium last year began livestreaming their activities around the clock on YouTube.

But, due to their popularity, a time limit at the sea otters’ enclosure was also introduced from March 17. Visitors are only permitted to stand in the viewing area for up to 1 minute.

On March 20, the first holiday following the introduction of the time limit, a long line formed.

Takashi Okura, a 66-year-old business owner from Osaka Prefecture and his wife Yuko, 66, expressed sadness that sea otter numbers have dwindled in recent years.

“We’ll miss them if they’re all gone,” Okura said.

According to Yoko Mitani, a professor of marine mammalogy at Kyoto University and an expert on sea otter ecology, the animals are being preyed upon by killer whales in Alaska, and their habitat is undeniably deteriorating.

Because sea otters live in cold regions, “rising sea temperatures due to global warming pose another threat,” she pointed out.

One ray of hope is confirmation that a population of sea otters has established itself off the eastern coast of Hokkaido, Japan’s northern main island, in recent years.

“Now that attention to sea otters is growing, we should face dealing with their situation head-on,” Mitani said.

Yoshito Wakai, director of Toba Aquarium, is pictured on March 20, 2025, in Toba, Mie Prefecture. (Photo not for sale)(For editorial use only)(Kyodo) ==Kyodo

The Toba Aquarium keeps approximately 1,200 marine species, the most of any aquarium in Japan. In addition to sea otters, it has Japan’s only dugong in captivity, and it was the first place in the world to successfully breed finless porpoises.

There is no suggested path for visitors to follow at the aquarium, allowing people to have unique experiences such as walking through a transport tunnel with marine mammals. The aquarium also engages in research, conservation projects and educational activities using the animals in its care.

“I hope that people come to see the sea otters here and get a true sense of the attraction, prompting them to learn even more about these marine mammals,” Toba Aquarium President Yoshihito Wakai, 65, said.

Related coverage:

FEATURE: Rising pit bull attacks in Japan put spotlight on negligent owners

Chimps solve complex problems better when watched by audience: study

Demand for pet funerals stronger than ever in Japan

AloJapan.com