JAPANESE STREET FOOD: WHY JAPAN AVOIDS MEAT FOR THOUSANDS OF YEARS

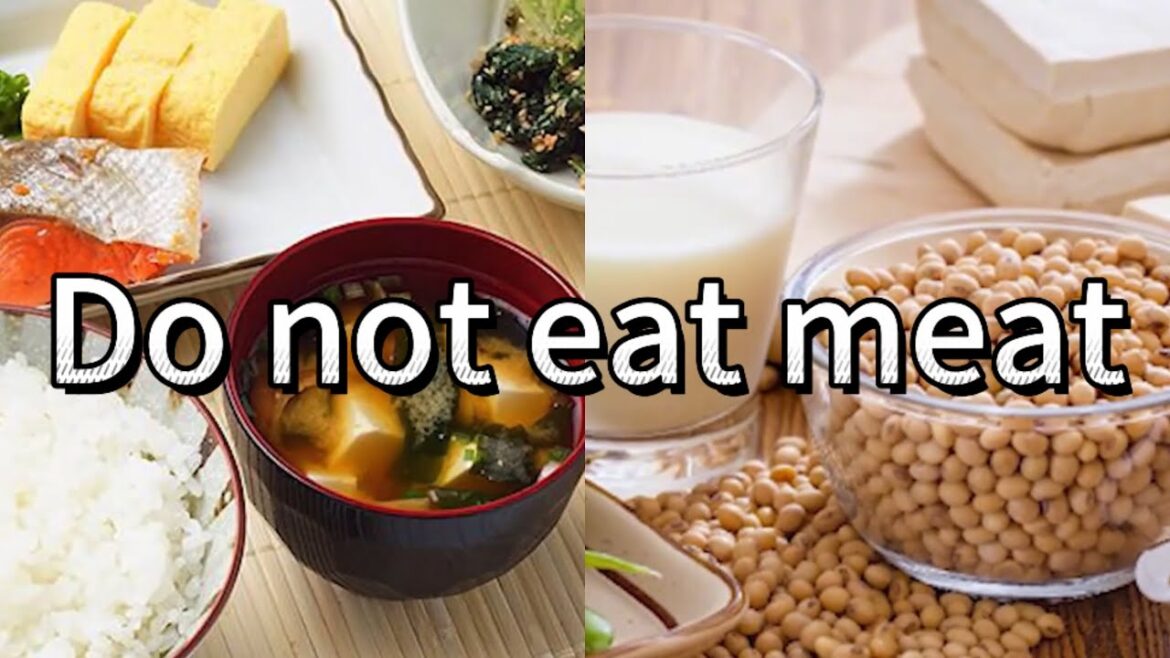

For over a thousand years, from the 7th century to the 19th century, the Japanese people barely touched beef, horse meat, pork, or any four-legged animals. Instead of meat, they ate fish, tofu, rice, vegetables, and seaweed. From this, they created a cuisine that was simple, elegant, and deeply Japanese. Why would an entire nation avoid meat for such a long time? This is the story of Japan. We need to go back in time to the year 675 in the capital city of Asuka, a city of wooden houses and shrines nestled beneath the trees. At the time, the emperor of Japan was Emperor Tenmu. He made an unprecedented decision. He banned the consumption of meat from four-legged animals like cows, horses, monkeys, and dogs. This was no small matter. The ban was written on wooden plaques and sent throughout the country. From rice fields to windy coasts, everyone had to comply. From farmers to samurai wielding swords. Emperor Tenmu was not just a king. He was also deeply devoted to Buddhism, a new religion brought from China and Korea. Buddhism teaches that killing animals creates bad karma and disrupts inner peace. He wanted his people to live gently, avoid killing, and make the nation more serene. But the ban also served another purpose. It allowed the court to tighten control and unite the various tribes into a single unified Japan. When everyone follows one law, the country grows stronger. Buddhist monks in saffron robes traveled across the land to explain the ban. They told stories about how killing animals would bring suffering in the next life, which frightened many. Even though not everyone fully understood Buddhism, people began reducing their meat consumption. Still, not everyone followed the rules. In remote mountain areas where officials had little control, some people secretly hunted deer or wild boar. They kept it hidden because being caught could mean harsh punishment like losing their land or being exiled from the village. Even so, Emperor Tenmu’s decree changed the Japanese diet and began an era without meat that lasted a thousand years. To understand why the Japanese avoided meat for so long, we must consider Buddhism, a religion that deeply influenced the people of that time. Buddhism came to Japan in the sixth century and quickly won the favor of nobles and officials. Monks taught that all living beings have souls and killing them for food was a sin. Eating meat wasn’t just about hunger. It polluted the soul and made inner peace harder to find. In mountain temples, monks lived meat-free lives and developed a unique style of cooking we now understand as vegetarian. These vegetarian dishes were both delicious and beautiful. They used tofu as soft as clouds, fragrant miso, sweet wild mushrooms, and fresh vegetables. A vegetarian meal was often quite diverse, made up of many small dishes, each arranged on wooden trays like a painting. These dishes were not just for eating. They brought calmness to the spirit in line with Buddhist ideals. Wealthy families and officials in cities also adopted monastic eating habits. They saw vegetarianism as refined, a sign of morality. At large banquetss, you would not see beef or horse meat. There was only grilled fish, white rice, and vegetables. Gradually, city dwellers began to follow suit, even if not all of them were Buddhists. Many started to believe that avoiding meat was simply the right way to live. It wasn’t just Buddhism. Shinto, Japan’s ancient religion, also made people hesitant to eat meat. Shinto holds that mountains, rivers, trees, and of course, animals all have spirits known as kami. Horses used in shrine ceremonies were seen as messengers of the gods. Cows, which helped farmers plow fields, symbolized abundance. Eating these animals was considered disrespectful, polluting both body and soul. In Shinto rituals, everything had to be pure. Blood and meat were seen as unclean. So only offerings like dried fish, rice or vegetables were presented to the gods. A simple tray with sake, grilled fish, and daicon radish. Carefully arranged showed devotion. This mindset affected daily life. Many Japanese people avoided meat not just because of the law, but because they believed it brought them closer to nature and the divine. Buddhism, which preached compassion, and Shinto, which emphasized purity, together built a wall that separated the Japanese people from meat. Eating meat became not only a legal issue, but something unnatural in the eyes of many. So, what did the Japanese eat instead of meat? Japan is a land of mountains and sea, and its natural environment allowed people to thrive without meat. About 70% of the country is mountainous with no wide pastures for raising cows or pigs like in Europe. Instead, the Japanese cultivated rice in small patties. Rice became the staple food, the heart of every meal. A hot bowl of white rice wasn’t just filling, but a symbol of the farmer’s pride. The sea surrounding Japan was like a treasure trove. Mackerel, sardines, shrimp, squid, and seaweed were everywhere. Fishermen would set out each morning and return with fresh catches. Fish was prepared in many ways. Grilled, salted, steamed with ginger, eaten raw as sashimi, or dried for storage. In coastal regions, a typical meal included grilled fish, rice, and seafood soup. Easy to make, easy to find, and no one felt the absence of meat. Soybeans also played a central role in the Japanese kitchen. From soybeans, people made tofu, miso, soy sauce, and even natto, a fermented, strong smelling, but highly nutritious dish. Tofu was cheap, easy to prepare, and could be turned into hundreds of dishes. In places far from the sea, tofu was the main source of protein, and was often jokingly called the meat of the poor. Miso was found in every household, used in everything from simple soups to hearty stews. Vegetables and mushrooms were also essential. Daikon radish, carrots, pumpkin, cabbage, and various mushrooms were grown everywhere. The Japanese preferred to cook them simply, boiled, steamed, pickled, or lightly stir-fried to preserve their natural sweetness. A typical daily meal might include rice, fish, soup, and a plate of fresh vegetables enough to be satisfying and beautiful to look at. Clearly, the meat ban transformed the way Japanese people lived. But not everyone followed the rules so easily. In major cities like Nara or Kyoto, where temples and officials were concentrated, people were used to avoiding meat. The markets there were full of fresh fish, tofu, and vegetables. Small shops sold noodles, rice balls filled with fish or steamed tofu. In wealthy households, meals were arranged like works of art with fish as the centerpiece. Meals were served with rice and plenty of vegetables, but things were quite different in remote mountain regions. People there continued to hunt deer, wild boar, and rabbits for food. To skirt around the law, they cleverly referred to these animals as mountain fish. Still, since fish and tofu were much easier to obtain, many people weren’t particularly fond of meat. For them, a meal with dried fish and vegetables was already delicious enough. This meat ban also changed how the Japanese viewed animals. Cows and horses were no longer seen as food, but as companions. Cows helped plow rice fields and horses carried goods. Killing them was considered wasteful, even immoral. Even guard dogs were protected, a sign of deep compassion. Emperor Tenmu’s meat ban didn’t end with his reign. It continued through different eras, sometimes enforced more loosely. During the Nar period, the court introduced laws banning the killing of animals during festival months called non-killing months, and encouraged the people to eat vegetarian meals as a show of devotion. By the Han period, vegetarianism became fashionable among the aristocracy. Lavish banquetss featured dozens of small dishes served on lacquered trays, steamed fish, tofu, mushrooms, turning meals into a form of art. Chefs competed to create beautiful dishes, elevating cuisine into an expression of elegance. Later, when the samurai class took power, some people did eat wild game, but kept it secret. Fish and vegetables remained the main stays of daily meals. Even during peaceful times, meat was rare. In Ido, modern-day Tokyo, markets were filled with fish, tofu, and soba noodles. Pork only began to appear when Western merchants arrived in Nagasaki, but commoners still rarely ate it. Though no longer strictly enforced, the meat ban had become a deeply ingrained habit in Japanese life. Everything changed during the Maji era in the late 19th century. Japan opened up to the west and the government sought to adopt western ways including their diet. It was said that eating meat made Europeans strong. So beef became a symbol of modernity. In 1872, Emperor Maji shocked the nation by publicly eating beef at a banquet. Newspapers called meat a superfood and encouraged people to give it a try. From then on, meat dishes began to appear in cities. Sukiyaki, a sweet beef hot pot, became a favorite. Tonkatu crispy fried pork cutlets also made its debut, but not everyone was immediately convinced. Some thought beef had a strange smell. Others feared it would make them impure. It took decades and the growth of railroads and livestock farming for meat to become truly widespread. Even so, fish, tofu, and rice have remained the heart and soul of Japanese cuisine.

3 Comments

Best content

I am animal lover

it's a matter of "water" and "fire" ki in their religion, both are needed but too much of one or the other causes a lack of balance

Bro you know fish is also meat right?