Bincsik says that it’s “getting more and more difficult to find kiribako craftsmen.” While out shopping recently, Kuwada was discouraged by how many mass-produced plastic boxes were for sale. In the early 1970s, her father sourced wood from the scraps of some 150 nearby kiri furniture makers; today, only a few of them remain. Acknowledging that hers is a fading practice, she’s been introducing new designs. The online success of a rounded vessel for baby teeth helped Kuwada and her staff of 15 get through the pandemic, and others have been used specially to hold umbilical cords or coffee beans. “The kiribako is beautiful,” said Suzuki. “But the whole idea is that it never distracts from the protagonist, which is what goes inside.” Yet without the care lavished on such containers, their contents could never attain the same level of significance or symbolism. A thing designed to ensure the legacy of other things, the box itself has become one of the most ubiquitous objects in Japanese design and iconography: form forever bound up in purpose.

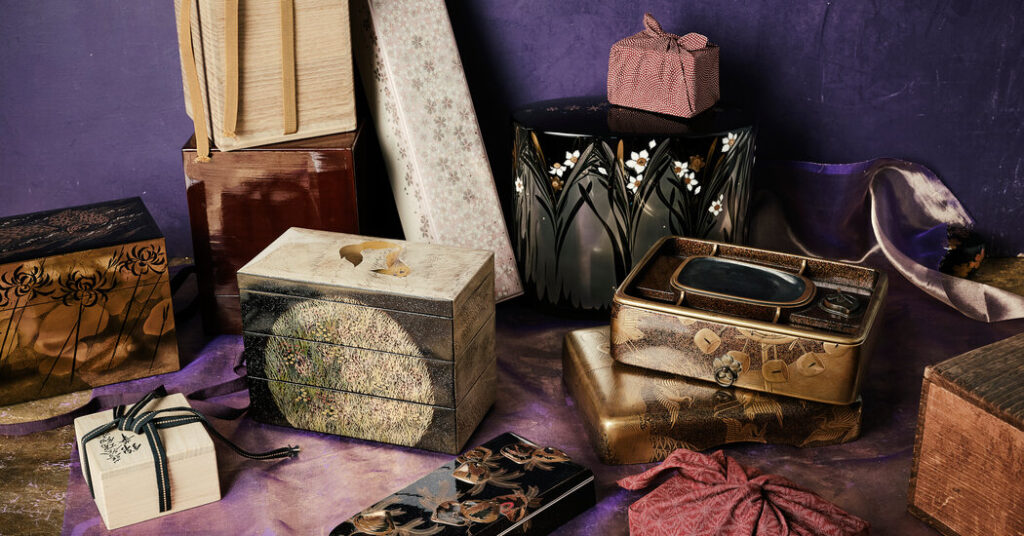

At top, clockwise from far left: Yuji Okado, “Meadow,” 1994, courtesy of Onishi Gallery, New York; Rokubei VI Kiyomizu, courtesy of Joan B. Mirviss Ltd., New York; Yoshiharu Sakashita, “Massed Cherry Blossom,” 2024, courtesy of Onishi Gallery, New York; Keiji Onihira, “Kinsangindai” (Narcissus), 2018, courtesy of Onishi Gallery, New York; Goryo Ichanaka, “Snow, Moon and Flowers,” 1990s, courtesy of Thomsen Gallery, New York; outer wooden box for writing, courtesy of Thomsen Gallery, New York; 19th-century maki-e gold-lacquer artist box for writing, courtesy of Thomsen Gallery, New York; Mushu Yamazaki, maki-e gold-and-silver-lacquer box with shell inlays and silver rims, courtesy of Thomsen Gallery, New York; Toyoshi Suzutani, “Rising Storm,” 2017, courtesy of Onishi Gallery, New York; outer wooden box for Kazumi Murose, courtesy of Onishi Gallery, New York.

Photo assistant: Berk Doan. Set designer’s assistant: Frida Fitter

AloJapan.com