Emika Kobayashi looks at photos while reminiscing, in the city of Osaka on July 29, 2024. She now runs a nonprofit organization and continues to support those with a cleft palate, their parents and others. (Mainichi/Yumi Shibamura)

OSAKA — When she was born, she had no discernable lips, ears or nose. The resident of this west Japan city was among the roughly one in 500 to 600 babies born in the country with a cleft palate, in which the lips, mouth or upper chin are split.

After undergoing more than 20 procedures, she now supports others with the congenital disease and their parents. In spite of prejudice and setbacks, she has found meaning in life, and she wants parents of children with the condition to know they needn’t feel sorry for bringing their children into the world.

Now 30, Emika Kobayashi was born with undeveloped lips and was diagnosed with a major form of the condition. At three months old, she had surgery to create a closure for her lips, followed by later procedures such as transplanting bone and skin to create earlobes. She underwent at least 20 such operations by the time she was 27.

“I was shocked by my appearance, which went beyond what I imagined,” she said of the first time she saw a photo of herself as a newborn in her medical history chart.

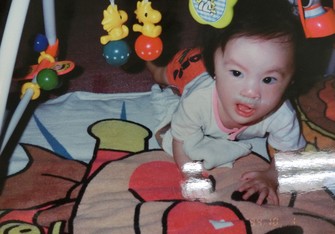

Emika Kobayashi is seen shortly after birth in this photo she provided. She was diagnosed with a serious cleft palate.

Kobayashi was 4 years old when she first became conscious of her appearance. She was teased by her friends at day care, and thought even in her young mind that she wanted “to disappear.”

As an adolescent, Kobayashi stopped attending school due to trouble getting along with others. She became fearful in life as she noticed passersby looking at her strangely or pointing their fingers. Very aware of people’s stares, wearing a mask became indispensable. To avoid worrying her parents, she cried in the shower. She even resorted to self-harm. “I couldn’t accept my existence as someone with a disease. I couldn’t show my weakness to anyone and kept it to myself,” she remarked.

It was the friends she met in high school who saved Kobayashi, who had retreated from life. Her classmates at a correspondence school struggled with circumstances of their own. She felt that she wasn’t the only one with challenges. Having others nearby with whom she could share her feelings enabled her to move forward and do her best for her friends’ sakes. After starting to research makeup, she became less conscious about her appearance. “Looking back, I think I was the one that was most prejudiced,” she said.

Nine years ago, after meeting a mother of a child with the condition, she heard of the woman’s concerns that there was no organization for those affected by the disease to meet. Wishing to share her feelings with others likewise affected, she started organizing events in Osaka, and now runs the nonprofit group Angel Smile Association, which she set up in 2020. “I want to create a society where people no longer have to be hurt emotionally by the scars they bear,” she said.

This photo provided by Emika Kobayashi shows herself as an infant.

Kobayashi consults with those who have the disease and their kin, who face a variety of circumstances. She recalls one mother contacted her soon after giving birth and tearfully confided, “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do.”

What erodes the feelings of patients are society’s prejudices and lack of understanding. Kobayashi said, “We want to break down those barriers by letting more people know about the disease and the patients who have it.”

The symptoms of a cleft palate vary, and those affected all have their own ways of thinking. Each has their worries, and each has their life. Kobayashi, who found light at the end of a dark tunnel, stated, “I want to send out the message that I’m happy to be alive.”

(Japanese original by Yumi Shibamura, Osaka City News Department)

AloJapan.com