Open this photo in gallery:

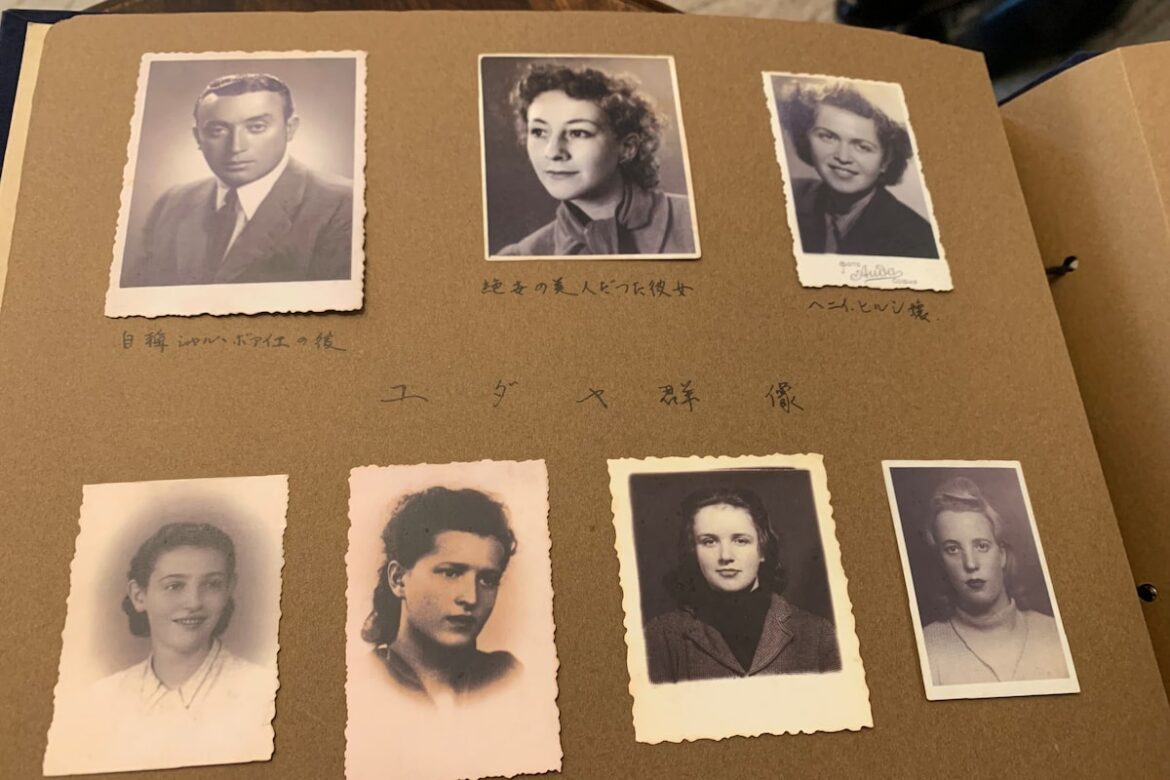

The discovery of a scrapbook, which included seven passport photos of young people, with personal messages in French, Bulgarian, Norwegian and Polish inscribed on the back, set Akira Kitade on a quest spanning decades to find out who they were.Supplied

Akira Kitade was about to retire after a lifetime of service at Japan’s tourist bureau, when his boss took a scrapbook off the shelf in his home and showed it to him. In it were photographs of his boss as a young man on a boat bound for Japan with Jewish refugees during the Second World War.

The discovery of the scrapbook, which included seven passport photos of young people, with personal messages in French, Bulgarian, Norwegian and Polish inscribed on the back, set Mr. Kitade on a quest spanning decades to find out who they were.

This week in Ottawa, at an event hosted by Kanji Yamanouchi, Japan’s ambassador to Canada, Mr. Kitade told how the mystery had finally been solved in Canada. A Montreal photographer had recognized a photo of a beautiful young woman in the scrapbook, sparking a train of other discoveries.

In an interview, Mr. Kitade described how the passport photograph, signed Zosia, with a note scrawled in Polish – “To a wonderful Japanese man – please remember me” – had haunted him. Her expression seemed to embody the anguish of Jews persecuted by the Nazis, he said, and he was compelled to learn her story.

The black and white passport photograph was one of several given to his boss, Tatsuo Osako, onboard a vessel bound from Vladivostok to Japan in 1940 and 1941.

As a young employee at the tourist organization, Mr. Osako had been tasked with escorting Jews by boat from the Russian port.

Their passage had been paid for by an American Jewish organization and they were allowed to enter Japan because of the courageous efforts of a junior Japanese diplomat posted to Lithuania. Defying official orders, Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara in 1940 issued 2,000 transit visas to refugees fleeing Europe to allow them to escape persecution and the Nazi death camps.

The visas he painstakingly wrote by hand were not officially sanctioned by the Japanese government that had sealed an alliance with Hitler’s Germany – but nor were they rejected.

Mr. Sugihara was imprisoned in a Soviet prisoner of war camp until 1947. Upon his return to Japan, the diplomat was summoned by his superior at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and asked to submit his resignation, according to his son, Nobuki Sugihara.

“My father got dismissed straight after reaching Japan after the war without any recommendations,” he said in an e-mail, saying he had been blamed for sending so many Jewish refugees to Japan.

Mr. Yamanouchi, in an interview, said Mr. Sugihara’s reputation has been rehabilitated in Japan and he is now regarded as a hero there.

“On the surface, what he did was a violation of discipline – a violation of his instructions,” Mr. Yamanouchi said. “Now we can easily say that he was right. We are very proud of him.”

At the event paying tribute to Mr. Sugihara, Mr. Kitade and children of Sugihara visa holders who made it to Canada recounted how the Japanese diplomat had defied authority to save thousands of Jewish people’s lives.

Judith Lermer Crawley described how her parents, both Sugihara visa holders, undertook an arduous journey from Lodz in Poland, to Lithuania, where they met Mr. Sugihara. With his transit visas in hand, they travelled through Russia, and then took a cargo ship to Japan from where they voyaged to Canada.

Her aunt, Zosia, had also escaped to safety after Mr. Sugihara wrote her a transit visa. She had travelled on the boat escorted by Mr. Osako to Japan and then on to the United States using the false identify of a woman who had died.

She changed her name from Zosia to Sonia when she arrived in the U.S., where she married and opened a clothing store.

She, it emerged, was that young woman staring out of the pages of the scrapbook who so mesmerized Mr. Kitade.

Mr. Kitade told The Globe he was “excited and thrilled” to find out who she was after years of searching. “The more I found out, the more curious I became,” he said.

In 2014 he had sent copies of the passport photos to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance centre in Jerusalem, to ask for help identifying them. It posted the photos online.

When Ms. Lermer Crawley saw them she immediately recognized her aunt, who had often come to Canada to visit.

Ms. Lermer Crawley contacted Mr. Kitade, telling him that her aunt had made it to New York from Japan. After she died in 1997, her family discovered she had kept the same passport photograph in the scrapbook, along with a business card belonging to Mr. Osako among her papers.

The discovery was followed by other breakthroughs, including identifying the only male passport photo as belonging to a Bulgarian called Nissim Segaloff. On arrival in the United States from Japan, he changed his name to Nicholas Sargent and went on to become a world-famous backgammon player.

Mr. Kitade, as he recounts in a book about his research, delved deeper into Mr. Sugihara’s actions and found that other diplomats had defied orders to help Jews fleeing Hitler reach Japan.

Among them was Saburo Nei, acting consul-general of the Japanese Consulate General in Vladivostok who, in defiance of instructions to limit the number of refugees entering Japan, himself issued Jews transit visas.

The Japanese foreign ministry, concerned by the large number of Jewish refugees arriving using Mr. Sugihara’s visas, sent telegrams to the Japanese embassy in Moscow saying that no further transit visas should be issued. And in 1941, Japanese foreign minister Fumimaro Konoe issued a directive saying that all transit visas for Jewish refugees should be reinspected and only stamped if the destination country’s requirements had all been met.

Objecting to the stringent restrictions, Mr. Nei boldly sent a telegram in response saying he “respectfully” disagreed with the order. He said – including for people heading to Canada – Japan should approve transit visas as it had before.

To comply with the order, Mr. Nei started issuing travel certificates. But he kept stamping Jewish refugees’ official documents – including Sugihara visas – so they could enter Japan.

In another cunning conceit to help Jewish refugees who had no onward destination beyond Japan – a requirement to enter the country – an ingenious Dutch consul, also based in Lithuania, helped them concoct one.

Jan Zwartendijk, based in Kaunus, Lithuania, issued papers allowing Jews fleeing Europe to claim their destination was – improbably – Curaçao, a tiny Dutch-controlled island in the Caribbean off the coast of Venezuela, which required no visa to enter.

The Netherlands was then occupied by Nazi Germany and Mr. Zwartendijk, like Mr. Sugihara, acted without official approval.

The father of Berel Rodal, a retired government official from Ottawa, was a young rabbinical student from Poland when he was given one of Mr. Sugihara’s visas, enabling him to escape to Montreal. This week at the event at the Japanese ambassador’s residence, Mr. Rodal likened Mr. Sugihara’s courage and sense of honour to that of a samurai.

“Sugihara simply was offended by the Nazi treatment of Jews,” he said. “He was a very ordinary man doing the right thing.”

AloJapan.com