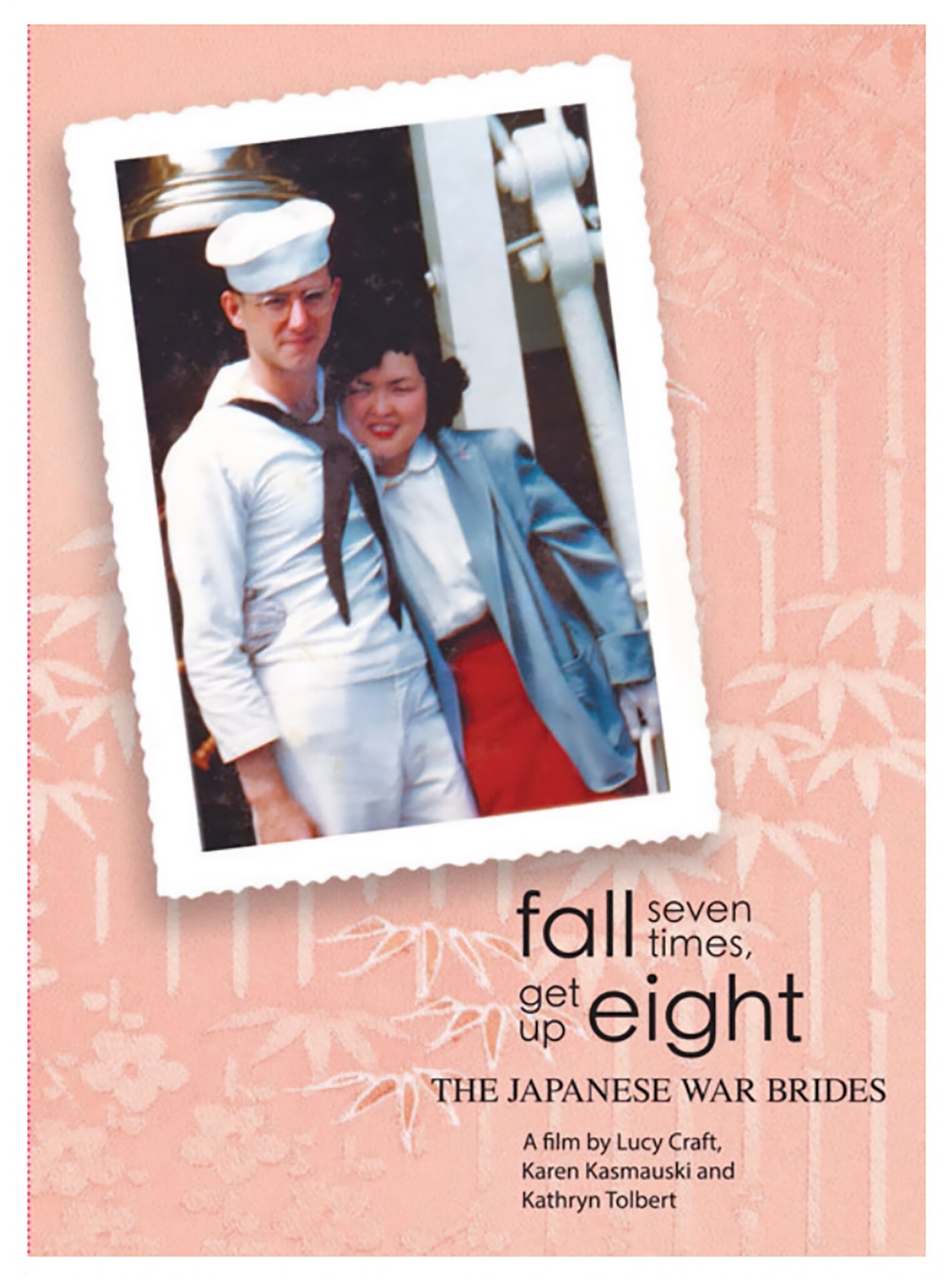

A powerful but underrecognized chapter in American history is the story of Japanese war brides—women who married American servicemen during and after World War II. These women, who left everything behind to start a new life in an unfamiliar land, played a vital role in shaping postwar United States and the Japanese American community. Their journeys and challenges are explored in depth in the documentary short Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight, a film by Blue Chalk Media in collaboration with Lucy Craft, Karen Kasmauski and Kathryn Tolbert, all of whom share a personal connection to the war brides through their own mixed-Japanese heritage.

I had the honor of working as a video editor with Tolbert on a new Smithsonian Institution exhibit dedicated to honoring these stories and exploring the impact these women had on both their families and their communities. As the granddaughter of a Japanese war bride myself, these stories left me with a profound sense of connection to the lives these women led and the sacrifices they made.

“Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight” is a documentary short film by Blue Chalk Media in collaboration with Lucy Craft, Karen Kasmauski and Kathryn Tolbert.

Steve Kasmauski

The research and work of Craft, Kasmauski, and Tolbert serve as the backbone of the traveling multimedia exhibit titled Japanese War Brides: Across A Wide Divide, which is currently at the Irving Archives and Museum in Irving, Texas, until April 6, 2025.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tal Anderson: Can you introduce yourselves and tell me a little about your backgrounds?

Lucy Craft: I’m Lucy Craft. I’m a journalist based in Tokyo, and for more than 10 years, I’ve been working with two partners on the history of the Japanese war brides in America. I want to say that all three of us were raised as white kids. In my case, though my mother took me to Japan several times as a child, everyone around me growing up was white. Any exposure I had to other cultures was fairly minimal.

Lucy Craft (middle) and her parents.

Courtesy of Lucy Craft

I was also sent to a Jewish Sunday school, so when I was an insecure teenager, I kind of defaulted to that identity. I ran a Jewish youth chapter, I worked on a kibbutz, I studied Hebrew, and I was all prepared to go and live and work in Israel. Then, all of a sudden, for various reasons, I had this unexpected detour to Asia, and I’ve lived here ever since.

I could never identify as Japanese, nor as Japanese American, which doesn’t really seem to fit who I am either. So I guess that “American expat in Japan” is the closest to who I am right now.

Karen Kasmauski: I’m Karen Kasmauski, and I’m a photojournalist and story developer. I have worked most of my career on stories about culture, women and the issues that concern them.

My father was enlisted in the military, so my world was a little different than Lucy’s. We did some traveling between the various bases, but the culture was military culture. When I was growing up, the Vietnam War and a lot of other issues were going on, and we were a little bit protected from that because we lived in the bubble of the military. But at the same time, we were very aware that there was conflict going on outside of this world that I lived in, which, because it was military, was a little more diverse than the normal suburban community.

The shock of my life was when we moved to the Chicago area, and for the first time, it was pointed out to me that I did not look like everybody else. People wanted to know where I came from, and whether I liked chop suey, etc. It was the first time that I started getting bullied because of the way that I looked, and it was kind of a shocker to leave that big military bubble to come into the so-called civilian world.

That got me interested in my background—who my mother was, why she married the enemy, and why my father married the enemy. All those questions started to rise, based on the reactions other people had to the way that I looked. Like other children of war brides, we were the only people in our community that looked like us. Most of us didn’t have other references to mixed race, so it was an interesting experience growing up outside of the naval base world where I spent most of my younger life.

Karen Kasmauski (left) and her parents.

Courtesy of Karen Kasmauski

Kathryn Tolbert: I’m Kathryn Tolbert. I’m a journalist, and I’ve been working with Lucy and Karen for more than a decade telling war bride stories.

I grew up in upstate New York, and like Karen and Lucy, I’m the firstborn daughter of a Japanese war bride. I was interested in Japan because of my mother, and she encouraged that interest, but she didn’t teach me Japanese. She did encourage me to go into journalism because she wanted to be a writer, and she always talked up newspaper work.

In fact, that’s where I ended up. I wanted to work in Japan, so I started studying Japanese. But as much as I loved working in Japan, it wasn’t exactly the Japan of my mother’s era. I didn’t really know or understand her very well, actually, until I met Karen and Lucy, and we started working on the War Brides Project.

TA: So how did you all meet, and how did you decide to pool your talents and resources to work together?

KT: I’ve been doing daily journalism for my entire adult life, and it was through journalism that I became connected to Lucy and Karen, although we work in different parts of media. I’ve done print—or what today is printed—and digital, starting out with The Associated Press and then moving to other newspapers. But I’ll let Karen and Lucy talk about how we met and what started that collaboration, because that really took my connection to Japan in a completely different direction. Karen, maybe you can speak to how we all started working together.

The Tolbert family.

Courtesy of Kathryn Tolbert

KK: I can add to that because my connection to Kathryn was very attached to my career. I worked as a contractor for National Geographic for a good portion of my career, and like Lucy and Kathryn, I was trying to understand who my mother was.

I think for many of us who were born during this time period, our mothers were a bit of a mystery to us for a lot of reasons. Some of us had good relationships with our mothers, and some of us had bad relationships with our mothers—mine was more on the bad side. I always wanted to know who this person was, and I pitched a story to National Geographic in the early ‘90s—or the late ‘80s actually—about Japanese women because I just wanted to know who these Japanese women were.

Anytime my mother would say something kind of ugly, my father would just say, “That’s just because she’s Japanese.” So my thought process was, “Who are these Japanese women? Why are they talking like this? Why are they saying things that are not appropriate?”

That’s how I got started. When I went to Japan, I connected with Lucy because she was a journalist working there. Someone gave me her name, and we talked quite a bit about Japanese women and our connection.

When I got back home, I met Kathryn through a project my husband was working on. Like me, she also wanted to understand her mother and was, I think, considering writing a book about her. Lucy contacted me a couple of years later and wanted to do a film about her mother, so I joined with Lucy, and we invited Kathryn to join the group. That’s how our group got started.

From left, Kathryn Tolbert, Lucy Craft, and Karen Kasmauski.

Courtesy of Kathryn Tolbert

TA: I watched your 2015 short film Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight: The Japanese War Brides, and it was incredible. My grandmother is also a war bride, and I learned a lot about her and the challenges she must have gone through by watching your film. Was this your first project together, and what did you set out to accomplish with the story?

LC: Our goals initially were very, very modest. I think a three-minute film was our first plan, so it was really about just trying to address this lacuna in American history.

One thing that always struck me is that if you search for “Japanese Americans” or anything related to the history of Japanese people in America, there’s a substantial body of work—as there should be—on the World War II internment camps. There’s also a fair amount about the so-called Japanese picture brides who immigrated to the U.S. to marry Japanese men before 1924. These were Japanese people marrying other Japanese people, and this was way before our moms arrived.

The record on Japanese War Brides was strangely thin. Because we’re all journalists, we felt like, “Wow, this is a great story that’s been overlooked, and it’s also an important one.” So that’s why we were motivated—not just from a personal level, but also as journalists—to address this story that had been missed.

KK: The problem with the film was that we had a hard time getting traction for it. There were a lot of people interested, but in the beginning, we thought it would be a five-minute film about Lucy’s mom.

I just happened to have a colleague named Rob Finch, who was part of a new startup production company called Blue Chalk Media. They loved the concept, so they created and started filming for a Kickstarter campaign. We had already done a lot of research and had quite a bit of footage we had produced for the Japanese War Bride Oral History Archive and the Library of Congress, but Rob didn’t think a five-minute film would do much.

Also, I think he knew where the industry was for a film like this and that it would be hard for us to raise money for it. He ended up generously giving us a longer film for a 30-minute broadcast, and we were all involved with it, using all three of our family stories and history. The end result was fabulous, and the film ended up being a sort of seed from which all other projects could grow.

The new Smithsonian exhibit explores the lives of the Japanese women who immigrated to America as wives of U.S. military servicemembers after World War II.

Prakash Patel Photography

TA: I was so honored to work with you, Kathryn, on the new Smithsonian exhibit Japanese War Brides: Across A Wide Divide, which honors the research and work the three of you have done over the last 10 years. How did the opportunity for the exhibit come about, and how did the work on this project over the last three or so years differ from your original work and film?

KT: When the film came out, we recognized that it was narrow in one sense because it was three mothers and three daughters. But in fact, it turned out to be a very effective way to tell a broader story.

We had always thought that it could be a kind of seed, and that we would eventually go on to do a longer film and include more diverse couples. We funded the short documentary through Kickstarter, and people donated and sent messages saying things like, “Oh… my grandmother… my mother… or I know somebody who’s a war bride, or who has an experience similar to your mom’s.” That really reinforced the idea that there were a lot of other stories out there.

I applied for and received a grant from my alma mater, Vassar College, to create the Japanese War Bride Oral History Archive. At that time, Vassar was giving a grant every year for an alum to stop doing what they were doing, and start doing something entirely different. My idea was to interview more families, and I started this in 2015.

While I was starting to interview people and create this collection of stories, the idea behind the exhibit was very much alive, but we didn’t have traction quite yet.

KK: At that time, before we made the film, I happened to be volunteering at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, where I met Sojin Kim, who had recently arrived from the Japanese American National Museum in L.A. to take a job as a curator with the Smithsonian.

I told her about this idea we had to create a film about Lucy’s mom and how it was a great way to look at the untold story about these women who came over to the U.S.—a history very few people know about. As a folklife curator, she thought it was fantastic. She introduced me to the curating team at the National Museum of American History, and that’s where a bunch of people had meetings about it. Kathryn joined in, and at that point, it felt very loose and all over the place for me, but I always thought the museum was my main goal.

I know Lucy wanted to make a film, and Kathryn wanted to write a book, but for me, I needed something where we could stand with other people—parents, mothers, grandmothers—and talk to them while looking at something tangible. That’s really hard to do with any other medium or venue, so I wanted to do the museum exhibit from the very beginning. I’m really glad that we finally got traction for the exhibit after the film was done.

It really all started with that serendipitous meeting with Sojin Kim. From there, the film got started, and eventually the exhibit came about.

AloJapan.com